Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current

WEBLOG

April 5th, 2025 (Permalink)

Pedaling Lies?

In September of 2023, California passed a law raising the state's minimum wage for certain fast food workers to $20 an hour, but it didn't go into effect until just about a year ago, at the beginning of April1. In a statement from his office in August of that year, Governor Gavin Newsom was quoted as saying about the new minimum wage: "Despite those who pedaled lies about how this would doom the industry, California's economy and workers are again proving them wrong.2"

The statement does not identify those who supposedly lied about the new minimum wage, but I doubt that anyone claimed that the raise of a few dollars an hour would actually "doom the industry", so this is an attack upon a straw man3. It's economic common sense that raising the cost of labor is likely to result in fewer employees, fewer hours worked, or higher prices, so some opponents of the raise did argue that it would cause job losses and price increases in fast food restaurants4.

However, the statement from the Governor's office claimed that California had added 11K new fast food jobs since the law had taken effect in April of that year, which is evidence that the job loss criticism was mistaken. Since the possibility of higher fast food prices was not addressed in the statement it is, presumably, lost jobs that the critics "lied" about.

There are two things wrong with the statement, one minor and one major. First, the bad news, then the worse.

- Pedaled or Peddled?

In the quote attributed to the Governor himself, Newsom accuses some unnamed people of having "pedaled lies". The verb "to pedal" means to operate a bicycle, piano or other machine with pedals5. Since lies don't have pedals, "to pedal lies" literally makes no sense and, even figuratively, it's hard to see the point of comparing lies to a bicycle or keyboard instrument.

In comparison, "to peddle" something means to sell it6, so that the common idiom "peddling lies" means to, at least metaphorically, "sell" lies. Since "pedal" and "peddle" are pronounced identically, it's no surprise that they are sometimes confused. Moreover, "peddle" is perhaps an unfamiliar enough word that people are unsure how to spell it. I suspect that most confusions of "peddle" and "pedal" come from people having heard the idiom "to peddle lies" but never having seen it spelled out, so that "pedal" is mistakenly substituted for "peddle".

Of the reference books that I usually check, only one lists this pair of words as a confusion to avoid7, so it may not be a very common error, but this is not the first time it's happened. Similarly, out of several free online spelling and grammar checkers I tried, only two suggested replacing "pedaled" with "peddled" in the Governor's sentence. In addition to such programs, I also ran it by GPT-4o mini, which responded:

The sentence you provided is generally clear, but it could be improved for clarity and flow. Here are a few suggestions:

- Punctuation: Consider adding a comma after "workers" for better readability.

- Clarity: The phrase "those who pedaled lies" could be rephrased to something like "those who spread misinformation" for a more neutral tone.

- Context: Depending on the audience, it might be helpful to specify what "this" refers to, as it could be unclear without additional context.

Revised example: "Despite those who spread misinformation about how this would doom the industry, California's economy and workers are again proving them wrong."

Overall, the original sentence conveys its message, but these adjustments could enhance its clarity and professionalism.8

This is a disappointing answer: the first suggestion is just plain wrong, and not even followed in the revised example. The second suggestion, about clarity, misses the misspelling of "peddled", and I doubt that the Governor would want "a more neutral tone". Finally, the last suggestion is quite correct, but is the result of taking the sentence out of its original context. The revised example corrects the "pedaled" mistake, but appears to have done so by accident.

Let's turn now to the second and more serious problem with the Governor's statement.

- Who Peddled Lies?

According to the statistics provided in the Governor's statement, which it attributes to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the number of fast food jobs in California increased by 11K in the four months after the wage increase went into effect. However, the BLS has since revised those figures and they currently show an increase of only 2.6K jobs, though it's still an increase9, so the Governor's argument is weakened but not destroyed.

Four months is a short period of time to judge the effects of such a major change, and it's plausible that it would take longer for the higher wages to lead to layoffs or less hiring. According to the BLS's current figures, in April of last year, the first month during which the higher wage would be in effect, the number of fast food workers in the state was 730K10. By December, the last month for which complete data is available, the number was down to 713.7K. So, according to the very source that the Governor relied on, the number of jobs lost in the fast food industry in the nine months after the new higher minimum wage was adopted, was 16.3K.

Now, I'm not claiming that all 16K jobs lost were the result of the higher minimum wage, but it's plausible that at least some were. Moreover, the Governor cannot get away with claiming that gaining 11K jobs in the first four months after the raise shows that it did not cost jobs and, at the same time, that 16K fewer jobs after five additional months has nothing to do with the raise.

Notes:

- Adam Beam, "New California law raises minimum wage for fast food workers to $20 per hour, among nation's highest", Associated Press, 9/28/2023.

- "After raising minimum wage, California has more fast food jobs than ever before", Governor Gavin Newsom, 8/20/2024.

- See: Straw Man.

- See, for example: Sara Chernikoff, "Fast food chains, workers are bracing for California's minimum wage increase: What to know", USA Today, 3/31/2024.

- "Pedal", Cambridge Dictionary, accessed: 4/5/2024.

- "Peddle", Cambridge Dictionary, accessed: 4/4/2024.

- Bill Bryson, Bryson's Dictionary of Troublesome Words: a Writer's Guide to Getting it Right (2002).

- Private chat with GPT-4o mini, 4/4/2025.

- "Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject", U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed: 4/4/2025. The BLS appears to classify so-called fast food restaurants as "Limited-Service Restaurants and Other Eating Places", which presumably includes some establishments not affected by the new law.

- This was the starting month that the Governor's office used in calculating that 11K fast food jobs had been created in the four months that the new wage had been in effect.

March 31st, 2025 (Permalink)

Now It Can Be Told

- Zeynep Tufekci, "We Were Badly Misled About the Event That Changed Our Lives", The New York Times, 3/15/2025

…[I]n 2020, when people started speculating that a laboratory accident might have been the spark that started the Covid-19 pandemic, they were treated like kooks and cranks. Many public health officials and prominent scientists dismissed the idea as a conspiracy theory, insisting that the virus had emerged from animals in a seafood market in Wuhan, China. … So, the Wuhan research was totally safe and the pandemic was definitely caused by natural transmission: It certainly seemed like consensus.

We have since learned, however, that to promote the appearance of consensus, some officials and scientists hid or understated crucial facts, misled at least one reporter, orchestrated campaigns of supposedly independent voices and even compared notes about how to hide their communications in order to keep the public from hearing the whole story. And as for that Wuhan laboratory's research, the details that have since emerged show that safety precautions may have been terrifyingly lax.

Five years after the onset of the Covid pandemic, it's tempting to think of all that as ancient history. We learned our lesson about lab safety―and about the need to be straight with the public―and now we can move on to new crises, like measles or the evolving bird flu, right? Wrong. …

Why haven't we learned our lesson? Maybe because it's hard to admit this research is risky now, and to take the requisite steps to keep us safe, without also admitting it was always risky. And that perhaps we were misled on purpose. …

…[T]ake the real story behind two very influential publications that quite early in the pandemic cast the lab leak theory as baseless. The first was a March 2020 paper in the journal Nature Medicine, which was written by five prominent scientists, and which declared that no "laboratory-based scenario" for the pandemic virus was plausible. But we later learned through congressional subpoenas…that while the scientists publicly said the scenario was implausible, privately, many of its authors considered the scenario to be not just plausible but likely. One of the authors of that paper, the evolutionary biologist Kristian Andersen, wrote…, "The lab escape version of this is so friggin' likely to have happened because they were already doing this type of work and the molecular data is fully consistent with that scenario."

Spooked, the co-authors reached out for advice to Jeremy Farrar, now the chief scientist at the World Health Organization. In his own book, Farrar reveals he acquired a burner phone and arranged meetings for them with high-ranking officials, including Francis Collins, then the director of the National Institutes of Health, and Anthony Fauci. … Operating behind the scenes, Farrar reviewed their draft and suggested to the authors that they rule out the lab leak even more directly. They complied.

Andersen later testified to Congress that he had simply become convinced that a lab leak, while theoretically possible, was not plausible. Later chat logs obtained by Congress show the paper's lead authors discussing how to mislead Donald G. McNeil Jr., who was reporting on the pandemic's origin for The Times, so as to throw him off track about the plausibility of a lab leak.

The second influential publication to dismiss the possibility of a lab leak was a letter published in early 2020 in The Lancet. The letter, which described the idea as a conspiracy theory, appeared to be the work of a group of independent scientists. It was anything but. …[T]he public later learned that behind the scenes, Peter Daszak, EcoHealth's president, had drafted and circulated the letter, while strategizing on how to hide his tracks and telling the signatories that it "will not be identifiable as coming from any one organization or person." The Lancet later published an addendum disclosing Daszak's conflict of interest as a collaborator of the Wuhan lab, but the journal did not retract the letter.

And they had assistance. …[T]he public learned that David Morens, a senior scientific adviser to Fauci at N.I.H. [National Institutes of Health], wrote to Daszak that he had learned how to make "emails disappear," especially emails about pandemic origins. "We're all smart enough to know to never have smoking guns, and if we did we wouldn't put them in emails and if we found them we'd delete them," he wrote.

Throat-clearing omitted.

The C.I.A. recently updated its assessment of how the Covid pandemic began, judging a lab leak to be the likely origin, albeit with low confidence. The Department of Energy…and the F.B.I. had already come to that conclusion in 2023. But there are certainly more questions for governments and researchers across the world to answer. Why did it take until now for the German public to learn that way back in 2020, their Federal Intelligence Service endorsed a lab leak origin with 80 to 95 percent probability? What else is still being kept from us about the pandemic that half a decade ago changed all of our lives?

To this day, there is no strong scientific evidence ruling out a lab leak or proving that the virus arose from human-animal contact in that seafood market. The few papers cited for market origin were written by a small, overlapping group of authors, including those who didn't tell the public how serious their doubts had been.

Only an honest conversation will lead us forward. … We may not know exactly how the Covid pandemic started, but if research activities were involved, that would mean two out of the last four or five pandemics were caused by our own scientific mishaps. Let's not make a third.

This assessment is appearing now because it's the five-year anniversary of the coronavirus panic of 2020. I usually oppose such anniversaries because of their arbitrariness, but it is useful to look back at one's past mistakes and try to learn from them. In that spirit, though I don't necessarily enjoy re-reading my own writing, I went back and re-read my first entry referencing the coronavirus from five years ago1. Thankfully, that post still holds up quite well against what we've learned since, but there was one mistake. In the section "Follow the Leader", I wrote:

Thankfully, …epidemics of panic seem to die out on their own fairly quickly, which is what I expect will happen in the next few weeks. There are already signs that people are calming down and reconsidering how to rationally respond to the spread of the disease, and March madness may, thankfully, die with the month.

This was overly optimistic. In fact, it took two or three years for the panic to subside, and it's not even completely over now. Historically, other similar epidemics of fear have died out within a few months or, at most, a year; for example, the Salem witchcraft panic died out within a year's time2, while the so-called Seattle windshield-pitting mass hysteria3 and the "mad gasser of Mattoon, Illinois"4 were over within months. It was with these and similar examples in mind that I expected the pandemic panic to die down within a few months or a year at most. It would appear that modern communications technology not only hastens and widens the spread of a panic, but it also makes it sustainable for longer periods of time.

I won't make that mistake again.

The following podcast is also from The New York Times:

- "Were the Covid Lockdowns Worth It?", The Daily, 3/20/2025

Short answer: no. Longer answer from the podcast itself or the transcript. There's too much worthwhile in the discussion to effectively excerpt, so I'll just say: listen to or read the whole thing.

Notes:

- March Madness, 3/28/2020.

- Jeff Wallenfeldt, "The trials", Britannica, accessed: 3/31/2025.

- Linton Weeks, "The Windshield-Pitting Mystery Of 1954", NPR, 5/28/2015.

- Brian Dunning, "The Mad Gasser of Mattoon", Skeptoid, 12/20/2016.

Disclaimer: I don't necessarily agree with everything in this article and podcast, but I think they're worth reading or listening to as a whole. In abridging the article, I changed some of the paragraphing.

March 29th, 2025 (Permalink)

Crack the Combination VIII*

The combination of a lock is four digits long and each digit is unique, that is, each occurs only once in the combination. The following are some incorrect combinations.

- 7 4 8 9: One digit is correct but in the wrong position.

- 9 1 2 6: Two digits are correct but only one is in the right position.

- 0 6 7 9: No digits are correct.

- 8 0 9 3: One digit is correct but in the wrong position.

- 0 6 8 1: One digit is correct and in the right position.

Can you determine the correct combination from the above clues?

4 3 2 1

Explanation: Clue 3 establishes that the digits 0, 6, 7, and 9 will not be in the combination, which means that the digits 1 and 2 will be in it, from clue 2, but we don't know in exactly what positions. From clue 5, we can conclude that 1 is in the last position, and that 8 is not in the combination. Returning to clue 2, we now know that 1 is in the wrong position, which means that 2 is in the next to last position in the combination. From clue 4, by a process of elimination, we can now conclude that 3 is in the combination, but we don't know where yet. From clue 1, we've eliminated all but 4, which is in the wrong position, so that it must be in the first position in the combination. Finally, 3 must be in the second position, which is the only one remaining.

*Previous "Crack the Combination" puzzles: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII.

March 27th, 2025 (Permalink)

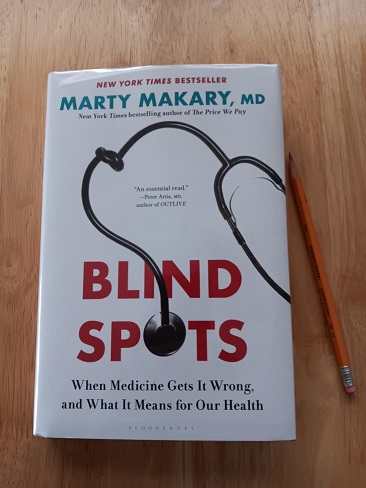

New Book

Quote: "This book may change your life. It did mine. You may forever view everything from menopause to microbiome health differently. You may also develop a reflex to ask for the underlying evidence or rationale to support a health recommendation…before you blindly abide by it. Having spent many hours with top doctors sorting scientific evidence from opinion on some of today's biggest health questions, I realize that much of what the public is told about health is medical dogma―an idea or practice given incontrovertible authority because someone decreed it to be true based on a gut feeling."1

Title: Blind Spots

Subtitle: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health

Comment: I would expect it means bad things for our health.

Author: Marty Makary

Comment: Makary is a physician and professor of medicine who has just been confirmed to head the Food and Drug Administration2. The only time I've written about Makary previously was in February 2021 when there was a large drop-off in Covid-19 cases3. Makary wrote an op-ed piece suggesting that the pandemic might be largely finished by April of that year due to the development of herd immunity. As I suggested at the time, this was overly optimistic. That prediction was, I suppose, the result of extrapolating out the then-current downward trend, but the only thing we know for sure about trends is that they don't continue4. At the time, it appeared that the decline might indeed be due to herd immunity, given that other explanations―such as bad weather, decreased testing, increased masking, and seasonality―didn't stand up to examination. Since herd immunity no longer seems to be a reasonable explanation, that leaves the decline unexplained.

Date: 2024

Comment: This book is not brand new since it was published last year before Makary was even nominated; what is new is that he will now have a powerful position in the health bureaucracy.

Summary: This book has an unusual structure: in the "Preface", Makary writes:

After the initial chapters, we'll pause and examine the human psychology of why we resist new ideas. You'll learn the mechanics of how our minds process new information when it conflicts with what we previously thought to be true. The human brain can do amazing things…[b]ut when it comes to receiving new information that conflicts with old information, it's predictably lazy5.

The initial chapters that Makary refers to appear to be discussions of specific medical errors about peanut allegies (1), hormone replacement therapy (2), over-use of antibiotics (3), and cholesterol (4). After that, we have a few chapters discussing why such mistakes are made, including intellectual inertia (5) and groupthink (10). In addition, there's a chapter on how the medical establishment works (6) and one on civil discourse (11). There are a few more chapters on specific medical issues, including birth (7), ovarian cancer (8), and silicone breast implants, autoimmune diseases, and opioid abuse (9).

Usually, in a book of this type, the general, theoretical chapters would be at the beginning, prior to those applying the generalities to specific cases; or, they would be at the end, deriving the generalities from the specific cases. Here, the generalities are sandwiched in between the specifics. I don't see any explanation by Makary for this odd structure, but perhaps the editor or publisher thought that a general readership would be discouraged if the book began by diving into theoretical discussions. Naturally, I'm most interested in those general chapters, but case histories of errors can be enlightening about the processes that lead to such errors.

Disappointingly, there is very little in the book about Covid-19 and the many errors made in dealing with the pandemic, with Makary writing: "This book does not discuss the Covid pandemic (people have become too tribal on the topic)….6" I certainly understand reluctance to deal with it while the wounds are still raw, but there's a danger of waiting too long, namely, that it will become a matter of purely historical interest.

Tribalism―in particular, political tribalism―is one source of medical error. For instance, taking seriously the idea that the novel coronavirus may have originated in a lab―the so-called lab leak theory―was taken as a sign of one's politics. Now, it's shedding its political force and becoming what it should have been all along, namely, a legitimate hypothesis7. Similarly, mask-wearing became as potent a political symbol as wearing a campaign button or a MAGA hat. How are we to fight such tribalism if we shy away from even discussing it?

Disclaimer: I haven't read this book yet, so can't review or recommend it, but its topic interests me and may also interest readers. The above remarks are based only on a sample of the book. I am not a physician. This entry is not intended to provide medical advice to individual readers. To obtain medical advice, the reader should consult a medical professional who will dispense advice based upon the reader's medical history and current medical condition8.

Notes:

- "Preface", p. xiv. All citations of just page numbers are to the New Book.

- Misty Severi, "Senate confirms Marty Makary to lead the FDA", Just the News, 3/26/2025.

- Have you heard of herd immunity?, 2/24/2021.

- See: Over-extrapolation.

- P. xv.

- P. 92.

- See: Kelsey Piper, "America―and the media―needs a Covid reckoning", Vox, 3/21/2025. I don't entirely agree with this article, but it's an admirable, if not totally successful, attempt on Piper's part to face up to past mistakes.

- The last two sentences are based on a "Publisher's Note" at the beginning of the New Book; p. ix.

March 12th, 2025 (Permalink)

21st Century Doublespeak, Part 3

Last month, I discussed the use of the phrase "immigrant living in the country without legal permission" as a euphemism for "illegal immigrant"1: I doubted that such a long phrase would catch on with the writers and editors at influential publications as a substitute for "undocumented immigrant" or "undocumented worker". Despite my doubts, an article earlier this month was published under the following headline:

What we know (and don't know) about immigrants living in the Houston area without legal permission2

As I mentioned in the previous entry, the careless use of the adjectival phrase "without legal permission" often leads to ambiguous sentences. Here, it sounds as though it's just living around Houston that's the problem, whereas I suspect that the immigrants in question lack legal permission to be anywhere in the country.

The first paragraph of the article under the headline includes the sentence: "No one knows exactly how many immigrants live in the U.S. without legal permission", which confirms my suspicion. The article repeatedly uses the phrase "without legal permission" and "undocumented" occurs only once in the phrase "undocumented immigrants", which is additional evidence that "undocumented" is on its way out.

The article even includes a helpful sidebar explaining the meaning of the phrase "without legal permission":

What does it mean to live in the U.S. without legal permission?

This population, sometimes referred to as the "unauthorized" population, includes those who entered the U.S. illegally (for example, by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border) and those who overstayed or violated the terms of their visas. …

The sidebar initially explains "without legal permission" with another euphemism, "unauthorized", but it helpfully explains that both euphemisms refer to those who either entered or remain in the country "illegally". Why can't they just say so, then? Interestingly, the article includes the following passage:

Put simply, researchers took a U.S. Census estimate of the total number of people who were not born in the U.S. and subtracted from that the total number of legal immigrants, as tallied by the Department of Homeland Security. The result gives a rough baseline of the number of people living in the U.S. without legal permission.

Why does the article refer to "legal immigrants" instead of "people living in the U.S. with legal permission"? Perhaps that's a bit too long-winded. However, if it's permissible to write "legal immigrants" why is it impermissible to write "illegal immigrants"? If there are legal immigrants then there are illegal ones: otherwise, the adjective "legal" servers no purpose. For consistency's sake, one should write both or neither; for clarity's sake, both.

Notes:

- 21st Century Doublespeak, Part 2, 2/4/2025.

- Matt Zdun, "What we know (and don't know) about immigrants living in the Houston area without legal permission", Houston Chronicle, 3/5/2025.

March 8th, 2025 (Permalink)

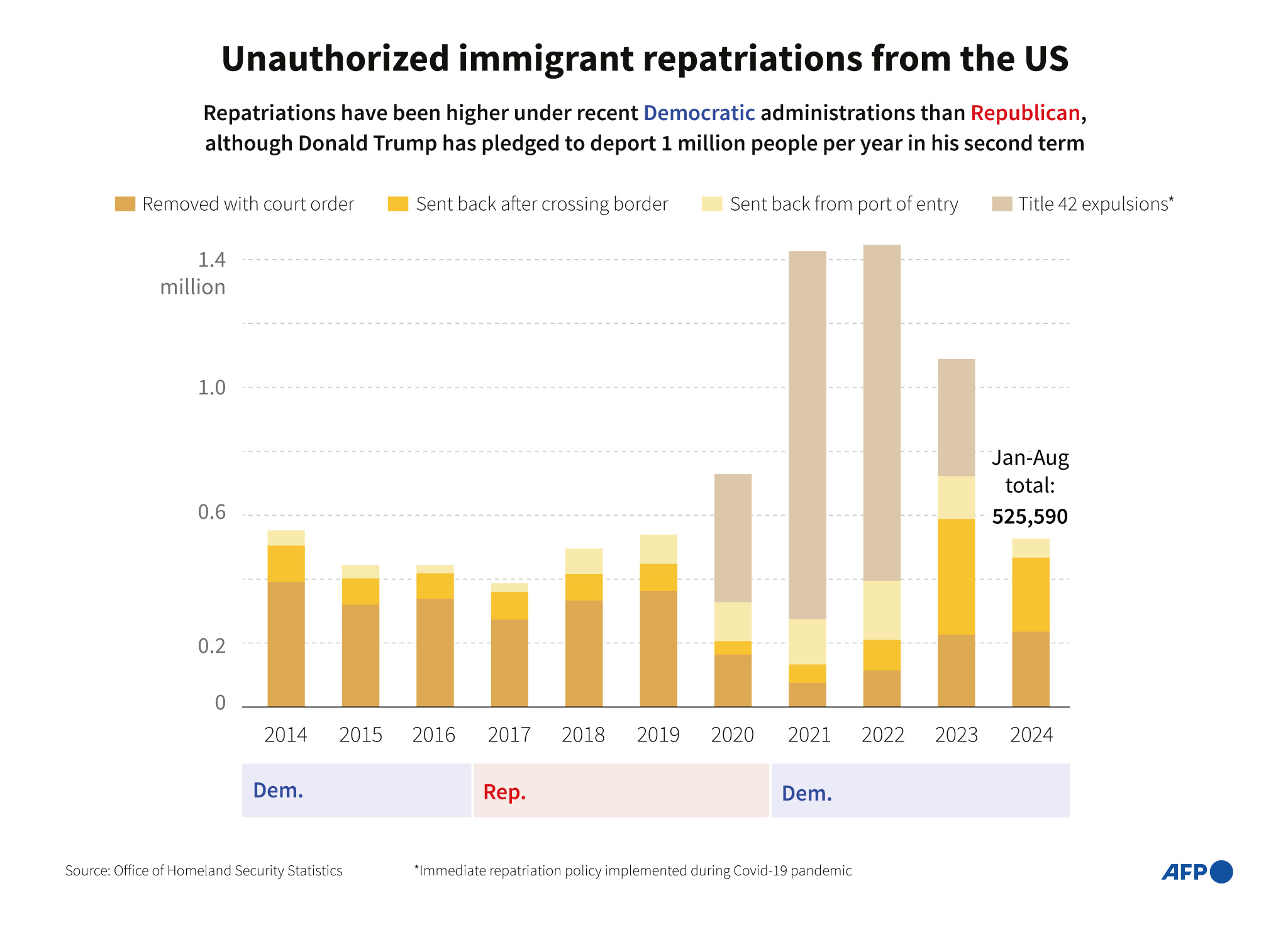

How to Tell Half-Truths with Charts & Graphs

Graphics must not quote data out of context.1

We saw in a previous entry how it's possible to tell half-truths with photographs2, and in this entry we'll see how to do it with charts and graphs. A chart that tells a half-truth is not one that lies; instead, it's one that tells the truth but not the whole truth.

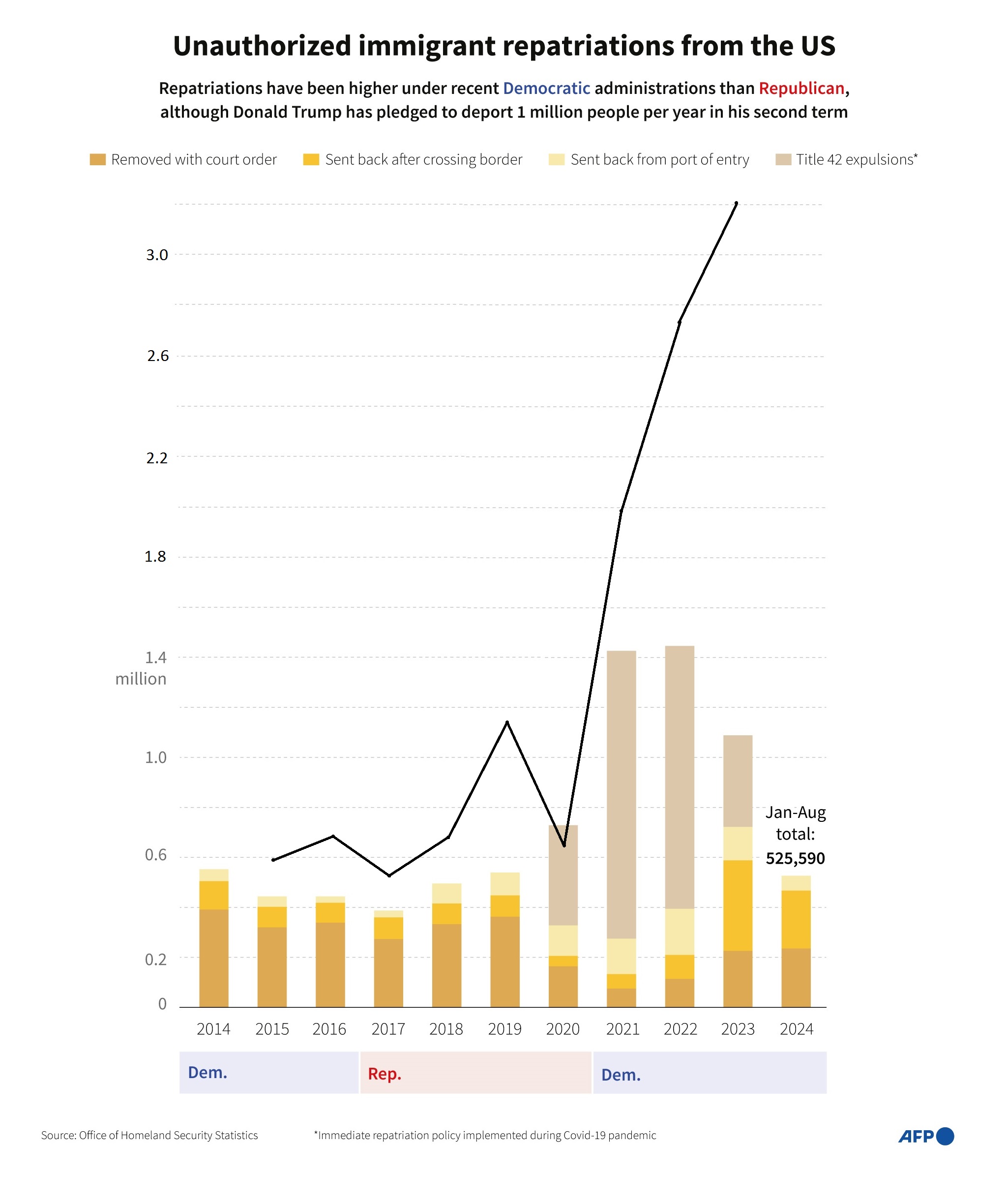

A bar chart appeared in an article in Newsweek about a month ago3 unfavorably comparing the numbers of deportations during Trump's first term to those under Biden's only term. A similar chart, shown above, appeared in Barron's about a month earlier4. The main difference between the two charts is that the Newsweek one breaks the data down by month, whereas Barron's one is broken down by year. Since I don't have the monthly data, I will concentrate on the above one in the rest of this entry, though the points made apply equally to both charts.

As far as I can tell, the statistical data displayed in the chart shown is correct5, but even so, the graph tells only half the story. The chart shows that many more "unauthorized"―that is, illegal―immigrants were repatriated to their countries of origin under the Democratic Biden administration as opposed to the previous Republican Trump administration.

Why is this data interesting? Given that the former and current president has been so gung-ho on expelling those who came here illegally, it's perhaps surprising that the previous one seems to have deported many more such immigrants. Based on the chart, should we conclude that Biden was actually a much more aggressive enforcer of the immigration laws than Trump, despite the latter's bluster?

What's wrong from this picture? The chart shows us only half of the picture: it only shows those being sent out of the country, not those coming in. Yet, the number of repatriations is partly a function of how many cross the border illegally and are subsequently "encountered" by agents of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Of course, not all illegal border crossers are encountered by the CBP, but this is the only measure we have of the number of such crossings. Everything else being even, the more who cross illegally, the more who will be encountered, and the more repatriated.

So, what is missing from the chart are the numbers of encounters by the CBP in the relevant years. Thankfully, the Office of Homeland Security Statistics (HSS) provides a chart showing the number of encounters for the past ten years6. Below, I've revised the above chart to incorporate the total number of encounters nationwide for each year based on the HSS's data7.

It's not a pretty chart: if I were constructing it from scratch, I would use a more compact scale, and only lines for comparisons, but at least the revised chart tells the other half of the truth. As you can see for yourself, the most notable feature of the revised chart is the huge spike in encounters for the years 2021-2023, that is, in the first three years of the Biden administration. The number of encounters almost tripled from the high in 2019 under Trump―1.1 million―to the high under Biden in 2023―3.2 million. So, no wonder there were so many more repatriations during the Biden administration than during Trump's first term: there were many more to repatriate.

Notes:

- Edward R. Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (1997), p. 77. This is the last of Tufte's six principles of graphical integrity.

- How to Tell Half-Truths with Photographs, 2/12/2025.

- Dan Gooding, "Trump Migrant Deportation Numbers Compared to Obama, Biden", Newsweek, 2/11/2025.

- Corin Faife, Valentina Breschi & Omar Kamal, "Unauthorized Immigrant Repatriations From The US", Barron's, 1/17/2025. A French version of the graph can be viewed here: "Investiture de Trump: les migrants, un marché à plusieurs milliards de dollars pour les mafias", La Croix, 1/19/2025.

- It's difficult to be sure since the only precise number given is for part of last year, and otherwise one has to try to read the numbers off the scale at the left, but the amounts appear to be approximately correct.

- See: "CBP Encounters", Office of Homeland Security Statistics, 2/11/2025.

- 2014 is not included because that year is not included in the table―see previous note; also, I've left out the number of encounters for last year, since the chart includes only partial data for the year and the table is not broken down by month.

March 6th, 2025 (Permalink)

Oh, Snap!

Here's a recent headline from Newsweek based on two "snap" polls1 conducted right after Trump's big speech a couple of nights ago:

Donald Trump's Congress Speech Was a Huge Hit With Americans2

These polls, which are the only ones I could find that were done since the speech, showed similar results: in one sponsored by CBS News3, 76% of respondents approved of the speech; in one from CNN4, 69% had a positive reaction.

The target population for both surveys was those American adults who watched the address, and not American adults in general. In public opinion surveys, a sample is taken of the "population", which is the group you want to know about, then the results for the sample are extrapolated to the population as a whole. In both of the snap polls, the population sampled was American adults who watched the speech, not American adults in general. For this reason, the poll results can only be extrapolated to the population of those who watched the address, and not to Americans as a whole, contra Newsweek. This is a fundamental point about sampling: a sample can only tell you about the population sampled, and not some other population, not even a larger one of which the sampled population is a subgroup.

Given that Republicans and Trump supporters are more likely to watch a speech by the president than Democrats and Trump opponents, adult address-watchers is a self-selected subgroup of the more general class of adults. This fact is reflected in the CBS survey in which slightly over half of those polled were Republicans and only a fifth Democrats; for the CNN poll, 44% were Republicans and also about a fifth Democrats. So, Republicans were over-represented in the samples and Democrats under-represented.

CNN's report did a good job of explaining this point:

Good marks from speech-watchers are typical for presidential addresses to Congress, which tend to attract generally friendly audiences that disproportionately hail from presidents' own parties. In CNN's speech reaction polls, which have been conducted most years dating back to the Clinton era, audience reactions have always been positive. The pool of people who watched Trump speak on Tuesday was about 14 percentage points more Republican than the general public.5

Another drawback of CNN's poll is its small sample size―only 431―and correspondingly large margin of error (MoE)―5.3 percentage points. In contrast, the CBS poll had a more usual sample size of 1,207 and MoE of 3.4 points. This is something to keep in mind about any snap poll, since such polls must be put together quickly and are, therefore, likely to have smaller samples and larger MoEs than standard polls.

Given the above considerations, there's not much news in either of the two snap polls. Mostly, what we learned is that people who watch Trump's speeches tend to agree with what he says. Big deal.

Notes:

- The word "snap" applied to a poll does not appear to have a technical meaning, but seems to refer to a topical poll taken quickly.

- Ewan Palmer, "Donald Trump's Congress Speech Was a Huge Hit With Americans", Newsweek, 3/5/2025.

- Anthony Salvanto, Jennifer De Pinto, Fred Backus & Kabir Khanna, "Poll on Trump's 2025 joint address to Congress finds large majority of viewers approve", CBS News, 3/5/2025.

- Ariel Edwards-Levy, "CNN poll: Trump address to Congress gets modestly positive marks, changes few minds", CNN, 3/5/2025.

- See the previous note. Paragraphing suppressed.