Appeal to Force

Alias:

Taxonomy: Logical Fallacy > Informal Fallacy > Red Herring > Appeal to Consequences > Appeal to Force3 < One-Sidedness < Informal Fallacy < Logical Fallacy

Example:

Students stormed the stage at Columbia University's Roone auditorium yesterday, knocking over chairs and tables and attacking Jim Gilchrist, the founder of the Minutemen, a group that patrols the border between America and Mexico. Mr. Gilchrist and Marvin Stewart, another member of his group, were in the process of giving a speech at the invitation of the Columbia College Republicans. They were escorted off the stage unharmed and exited the auditorium by a back door. … The student protesters…booed and shouted the speakers down throughout. They interrupted Mr. Stewart…. A student's demand that Mr. Stewart speak in Spanish elicited thundering applause and brought the protesters to their feet. The protesters remained standing, turned their backs on Mr. Stewart for the remainder of his remarks, and drowned him out by chanting, "Wrap it up, wrap it up!" … On campus, the Republicans' flyers advertising the event were defaced and torn down.4

Exposition:

Appeal to force refers to the use of force and, by extension, the use of threats of force, or intimidation, to "win" an argument by preventing the other side from presenting its case.

Exposure:

There are two types of logical error that may be involved in appeals to force as indicated in the Taxonomy above:

- Some appeals to force are types of appeal to the consequences of a belief, that is, arguing that believing something will lead to bad consequences. What sets these apart from other appeals to consequences is that the bad consequences appealed to―that is, the threat of force―will be brought about by the arguer. In other words, if you don't believe what I want you to believe, I will punish you in some way. Attempts to change people's minds by threats of punishment are appeals to consequences, since the bad consequences appealed to are not consequences of what is believed, but of believing it. Such consequences are irrelevant to whether the belief itself is true or false.

However, because it is impossible to read a person's mind, the attempt to use force or threats to change minds is usually ineffective. Instead, threats are more commonly reasons to act, and as such can be good reasons to do so if the threat is plausible. People are sometimes intimidated into pretending to believe things that they don't, but this is not coming to believe something because of the fear of force. Nonetheless, the threat of violence can certainly be an effective way of silencing an opponent, which brings us to the second logical flaw:

- When force or the threat of force is used to suppress the arguments of one side in a debate, that leads to a type of one-sidedness, because only one side is heard. Governments are always tempted to use police powers to prevent criticism of their policies, and totalitarian governments are frequently successful in doing so. Extremists use threats or actual violence to silence those who argue against them. Audience members "shout down" a debater whom they disagree with in order to prevent a case from being heard. This is, unfortunately, a common tactic these days.

Since force or the threat of it is not an argument, appealing to force might appear not to be a logical fallacy. Simply hitting someone over the head with a stick is not an argument at all, so a fortiori it is not a fallacious one. However, withholding relevant information can lead people into drawing false conclusions, and is thus at least a logical boobytrap, that is, a tactic that may lead people into committing a logical fallacy.

Analysis of the Example: The example is an instance of the second type of appeal to force, that is, the use of force and the threat of it to prevent the other side of an argument from being heard.

Notes:

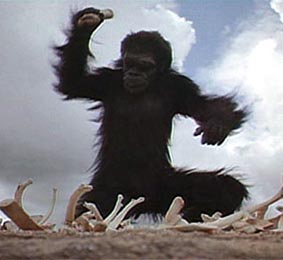

- Translation: "Argument from the stick", Latin. See: David Hackett Fischer, Historians' Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought (Harper & Row, 1970), pp. 294-296. Fischer translates "baculum" as a "big stick". A baculum or baculus was a staff or walking stick, probably often used as a truncheon. The name "argumentum ad baculum" alludes to the use of such a club to beat or threaten someone.

- Eugene Ehrlich, Amo, Amas, Amat and More: How to Use Latin to Your Own Advantage and to the Astonishment of Others (1985). Ehrlich gives the fallacy under this name, which translates the same as in the previous note.

- John Woods, "Appeal to Force", in Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings, edited by Hans V. Hanson and Robert C. Pinto (Penn State Press, 1995), pp. 240-250.

- Eliana Johnson, "At Columbia, Students Attack Minuteman Founder", The New York Sun, 10/5/2006.