Begging the Question

Alias:

- Circular Argument

- Circulus in Probando

- Petitio Principii

- Vicious Circle

Taxonomy: Logical Fallacy > Informal Fallacy > Begging the Question

Etymology:

The phrase "begging the question", or "petitio principii" in Latin, refers to the "question" in a formal debate—that is, the issue being debated. In such a debate, one side may ask the other side to concede certain points in order to speed up the proceedings. To "beg" the question is to ask that the very point at issue be conceded, which is of course illegitimate.

Misrule of Thumb:

Begging the question is a fallacious form of argument.

Therefore, to beg the question is to argue fallaciously.

Note: A "misrule of thumb" is a misleading "rule of thumb". I use the term to describe an argument that commits the very fallacy it is intended to show fallacious, as the above argument itself begs the question.

Form:

Any form of argument in which the conclusion occurs as one of the premisses. More generally, a chain of arguments in which the final conclusion is a premiss of one of the earlier arguments in the chain. Still more generally, an argument begs the question when it assumes any controversial point not conceded by the other side.

Example:

To cast abortion as a solely private moral question,…is to lose touch with common sense: How human beings treat one another is practically the definition of a public moral matter. Of course, there are many private aspects of human relations, but the question whether one human being should be allowed fatally to harm another is not one of them. Abortion is an inescapably public matter.

Source: Helen M. Alvaré, The Abortion Controversy, Greenhaven, 1995, p. 23.

Exposition:

To beg the question is to assume something that you have no right to assume. What don't you have a right to assume? The conclusion itself, obviously, or any proposition that is just the conclusion stated in different words. Clearly, to use any argument in which the conclusion is also one of the premisses is to reason in a circle: reasoning from the premisses to the conclusion brings you back to where you started.

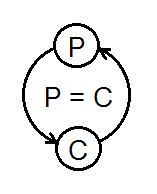

The simplest type of circular argument is an argument with a single premiss that is the same as its conclusion―see the first diagram to the right, where "P" stands for "premiss" and "C" for "conclusion" and the arrows indicate the direction of reasoning. Since P and C are the same proposition, we can also represent this argument with the second diagram, which shows that this is the smallest circle one can reason in.

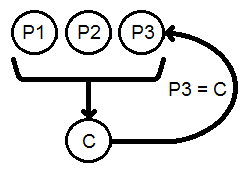

Now, this type of circularity is so obvious that it's not likely to occur in a real argument. Instead, real arguments will probably reason in larger circles; for instance, simply including additional premisses will make it difficult to spot the one that's the same as the conclusion. The next diagram shows an example with three premisses, the third of which is the same as the conclusion. However, the more premisses, the harder it will be to detect the circularity or identify which premiss is the same as the conclusion.

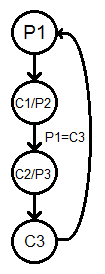

An additional way that circularity is concealed is by means of multiple arguments that link together in a chain or tree-like structure. For instance, consider a chain of arguments with three links, each of which is a simple, one-premissed argument. The three arguments are then joined by the fact that the conclusion of the first argument in the chain is also the premiss of the second argument, the conclusion of which is the premiss of the third argument―see the last diagram. Finally, the conclusion of the last argument in the chain is the same as the premiss of the first argument, which loops the chain back on itself.

Circularity is more difficult to detect in such complex arguments, but it's usually additionally concealed by the deceptive use of language: the question-begger states the same thing in different words, uses loaded language that presumes the point at issue, and often leaves unstated the premiss that creates the circularity. As a result, simply diagramming an argument as shown here may not reveal the circularity without first untangling the confusing use of language, which is part of what makes begging the question an informal fallacy in logic.

Exposure:

- Unlike most informal fallacies, Begging the Question is a validating form of argument, that is, every argument that begs the question is valid―if this seems surprising or confusing to you, see the Q&A, below. Moreover, if the premisses of an instance of Begging the Question happen to be true, then the argument is sound. What is wrong, then, with begging the question?

First of all, not all circular reasoning is fallacious. Suppose, for instance, that we argue that a number of propositions, p1, p2,…, pn are equivalent by arguing as follows, where "p → q" means that p implies q:

p1 → p2 → … → pn → p1

Then we have clearly argued in a circle, but this is a standard form of argument in mathematics to show that a set of propositions are all equivalent to each other. So, when is it fallacious to argue in a circle?

For an argument to have any epistemological or dialectical force, it must start from premisses already known or believed by its audience, and proceed to a conclusion not known or believed. This, of course, rules out the worst cases of Begging the Question, when the conclusion is the very same proposition as the premiss, since one cannot both believe and not believe the same thing. A viciously circular argument is one with a conclusion based ultimately upon that conclusion itself, and such arguments can never advance our knowledge.

- The phrase "begs the question" has come to be used to mean "raises the question" or "suggests the question", as in "that begs the question" followed by the question supposedly begged. The following headlines are examples:

Warm Weather Begs the Question:

To Water or Not to Water Yard PlantsLatest Internet Fracas Begs the Question:

Who's Driving the Internet Bus?Hot Holiday Begs Big Question:

Can the Party Continue?This is a confusing usage apparently based upon a literal misreading of the phrase "begs the question". It should be avoided, and must be distinguished from its use to refer to the fallacy.

Resources:

- Gary Curtis, "Please Stop Begging that Question You're Raising", The Editorial Eye, 2/2007

- Mark Liberman, "'Begging the question': we have answers", Language Log, 4/29/2010

Reader Response:

In your Etymological Fallacy "Exposition" section, you point out that "the meanings of words change over time." I state, with zero evidence beyond personal experience, that today most people use the phrase "begs the question" to mean "raises the question". I have found very few people who were aware of its "Petitio Principii" definition. When terms like "Circular Argument" are currently far more clear to the general population than "begs the question", why do you suggest that "begs the question" should cling to its older definition as opposed to being dropped for its current common usage? As I mentioned, I have no hard numerical evidence to back up my claim, but I believe the postulate would prove true if studied. I'm sure there would be variance between a Harvard Campus study vs. a ghetto study, but I believe the median American value would support it.―Dan Rotelli

I think that you're right about the common use of the phrase "begs the question", and the newspaper headlines above are evidence that it usually has the meaning "raises the question" among editors and journalists. You also make a good point about the alternative name "circular argument", or "circular reasoning", for this fallacy. These are far better names than the traditional one, since they give an idea of the logical nature of the mistake, as well as being more memorable. "Begging the question" has always been a puzzling phrase: Why "beg"? What question? Moreover, "begging the question" is a poor translation of the Latin phrase "petitio principii"; a more accurate translation might be something like "requesting first principles".

However, these are good arguments for dropping the phrase "begs the question" altogether, rather than using it to mean "raises the question". It's still a puzzling phrase when used in the common newspaper sense: why "beg" the question? Why should newspaper editors use "begs" instead of the available alternatives of "raises", "suggests", or "invites" the question? At best, what started out as a misuse of logical jargon to impress the reader has turned into an idiom because neither the writer nor reader knew what the phrase meant.

Perhaps saving the logical sense of "begs the question" for common use is a lost cause. However, it may not be a hopeless cause to get people to stop using the phrase at all.

Q&A:

Q: In Patrick J. Hurley's A Concise Introduction to Logic, (10th ed.) a True/False exercise is posed: "Arguments that commit the fallacy of begging the question are normally valid."

Now there certainly are a few things wrong with this question, not the least of which is that Hurley breaks "begging the question" down into three sub-categories, though most sources I've come in contact with cite only "circular reasoning" as the primary example of "begging the question." But he states, "The first, and most common, way of committing this fallacy [of begging the question] is by leaving a possibly false key premise out of the argument while creating the illusion that nothing more is needed to establish the conclusion."

He then gives an example, "Murder is morally wrong. This being the case, it follows that abortion is morally wrong." Here it seems to me that the example is an invalid argument. A key premise is missing, and thus the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the given premise. One might argue that the missing premise is implied, but if one accepts that then it seems the fallacy isn't an issue so much as the strength of the implied premise. After all, a valid argument is one in which if the premises are true, then it is impossible for the conclusion to be false. If there is only one premise and a second premise linking the first to the conclusion is missing, then it would be possible to have true premise(s) and a false conclusion, making the argument invalid. On this basis I answered "False" to the above question.―John Pocock

A: I don't have the tenth edition of Hurley's text; the latest edition I own is the fifth, from 1994. In that edition, as well as earlier ones that I also have, he actually defines "begging the question" as a type of valid argument (p. 153). I think that this is a mistake, but it means that the question you answered "false" would be true by definition. Of course, this raises―not "begs"―the question whether the abortion argument is in fact an example of begging the question; if it's invalid, then it can't be an instance of begging the question.

I think that it's a mistake to define "begging the question" as a type of valid argument because it's unnecessary, since all circular arguments are valid. As I mention in the Exposition above, begging the question is a validating form of argument. This sounds counter-intuitive, especially if you over-estimate the importance of validity. Validity is a virtue of arguments, but a good argument also needs to be sound. Moreover, as explained above, even soundness is not enough: a good argument must actually advance our knowledge or the debate we are in. Begging the question gets us nowhere, as we just end up going around in circles.

Why is a circular argument necessarily valid? This surprising fact is a consequence of the definition of "valid": a valid argument is one in which the truth of the premisses necessitates the truth of the conclusion. If the conclusion of an argument is one of its premisses, then clearly the truth of its premisses necessitates the truth of that conclusion, since if the premisses are true then the conclusion―which is one of them―must be true. Of course, the question of whether that premiss is true is what's at issue, which is why it's begged.

In the fifth edition, Hurley gives the same example and apparently considers "all abortions are murders" to be a suppressed premiss of the argument. So, Hurley takes the complete argument to be:

Murder is morally wrong.

All abortions are murders. (Suppressed)

Therefore, abortion is morally wrong.

This is certainly a valid argument. Moreover, it doesn't appear to be circular, since the conclusion is not one of the premisses. Why, then, does it beg the question?

It begs the question because the word "murder" is not a morally-neutral word, such as "killing". All murders are killings, but not all killings are murders. A person who kills someone in self-defense, a soldier who kills in battle, or a policeman who kills in the line of duty, is not a murderer. So, the first, unsuppressed premiss is really unnecessary, as the argument is valid without it:

All abortions are murders.

Therefore, abortion is morally wrong.

Or, to spell out what "murder" means:

All abortions are wrongful killings.

Therefore, abortion is morally wrong.

Which is clearly circular and, therefore, valid. In the original argument, the moral wrongness of abortion has been smuggled into the premiss via the morally loaded word "murder". This is how real-life questions are often begged, that is, by using loaded language to conceal the fact that an argument is circular.

Subfallacies:

Source:

S. Morris Engel, With Good Reason: An Introduction to Informal Fallacies (Fifth Edition) (St. Martin's, 1994), pp. 144-149

Resources:

- Robert Todd Carroll, "Begging the Question", Skeptic's Dictionary

- Douglas N. Walton, "The Essential Ingredients of the Fallacy of Begging the Question", in Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings, edited by Hans V. Hanson and Robert C. Pinto (Penn State Press, 1995), pp. 229-239

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Christopher Mork for a criticism which led me to revise the Form and add the Etymology and to Paul Freda for a stylistic criticism.

Analysis of the Example:

This argument begs the question because it assumes that abortion involves one human being fatally harming another. However, those who argue that abortion is a private matter reject this very premiss. In contrast, they believe that only one human being is involved in abortion—the woman—and it is, therefore, her private decision.