WEBLOG

Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

January 28th, 2012 (Permalink)

A Lapalissade

From an Agence France-Presse report:

Francesco Schettino told a friend he was following the advice of a manager about what route to take…media reported, quoting a call secretly recorded by police the day after the January 13 shipwreck that killed at least 16 people. … The luxury liner [captained by Schettino] capsized off the tiny Tuscan island of Giglio with more than 4,000 people on board. Sixteen people are still unaccounted for. … He added that he deserved credit for the fact that "I managed to save everyone, except them (the victims)."

Sources:

- "Stricken ship captain blames company pressure: reports", Agence France-Presse, 1/25/2012

- "If You Can’t Swim…", Funny Signs

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Tereza Šmejkalová for pointing out the quote and for the lovely title.

January 26th, 2012 (Permalink)

Mixed-Up Logic Check

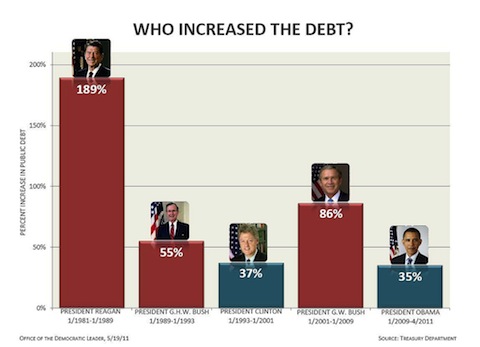

If you pay attention to the news, you might be excused for thinking that President Obama has increased the national debt much more than his predecessors in office. However, a bar graph put out by House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi's office, and later used by the liberal group MoveOn, purports to show that Obama has increased the debt less than each of the four previous presidents, and the three Republican presidents―Reagan, Bush père, and Bush fils―each increased the debt more than either of the Democrats―Clinton and Obama.

An earlier version of this chart (not shown) contained an error that exaggerated the amount of debt accumulated under Bush the younger and played down the amount under Obama. This error led the fact-checking site PolitiFact to award the chart a rating of "Pants on Fire" on its Truth-o-meter last year (see the Source, below) when the chart was first circulated, but it has since been corrected (shown). So, the percentages given on the chart are now correct, but what do they mean?

One way you might try to get a rough measure of the differing contributions of different presidents to the current debt would be to calculate what percentage of that debt was contributed by each president. However, this chart clearly does not do that, since the percentages add up to more than 100%―in fact, Reagan's percentage alone is nearly 200%.

Instead, the label on the y axis is "percent increase in public debt", that is, the height of the bars indicates how much public debt increased during each president's term as a percentage of the debt at the beginning of that term. For instance, according to the chart, the debt nearly tripled during Reagan's term, that is, the amount of debt added under Reagan was almost double the existing debt. According to PolitiFact, the debt at the beginning of Clinton's term was about $4.2 trillion, and the amount at the end was a little over $5.7 trillion, so that $1.5 billion was added during his term, which is 37% of $4.2 trillion.

So, if the percentages in the chart are now correct, what's the problem? The problem is that during the thirty years covered by the chart, the national debt has steadily increased. The chart itself shows this, since if any president had managed to lower the debt, his percentage would be negative. As a result, the starting debt from which each president's percentage is figured is different, and the chart is thus comparing apples to oranges. As Glenn Kessler, the Fact Checker for The Washington Post pointed out in criticizing the corrected version of the chart:

The chart has some basic conceptual flaws. For instance, as the debt keeps getting higher, the possible percentage increases will keep getting smaller. Under the mixed-up logic of this chart, a person can go from 10 to 20, and that would be a 100 percent increase. If the next person goes from 20 to 30, that’s only a 50 percent increase, even though the numerical increase (10) is the same.

Given the constantly increasing debt, the later a president's term, the smaller the percentage he adds to the debt will tend to be. This is one reason why Reagan's percentage increase is so much bigger than any other president―because the debt was at its smallest at the start of his term―and why Obama's is the smallest―since the debt was higher at the start of his term than at the start of any previous president's. So, the chart is inherently biased against the earlier presidents and in favor of the later ones, that is, the percentages of the earlier presidents will be inflated and those of the later ones diminished.

In this case, comparing absolute numbers is more revealing than comparing percentages. For example, George W. Bush added nearly $4.9 trillion to the debt, whereas Obama has added about $3.7 trillion. So, the debt racked up under Obama is in fact about three-quarters of that added under the second Bush, rather than less than half as the chart seems to show.

This brings us to another way in which the graph is comparing apples and oranges: Reagan, Clinton, and Bush 2, were all two term presidents, serving eight years in office, whereas Bush 1 served one term of four years, and Obama has so far served only a little over three years. So, under Obama it's taken only three years to add 75% of what took eight years under George W. Bush.

Sources:

- Louis Jacobson, "Nancy Pelosi posts questionable chart on debt accumulation by Barack Obama, predecessors", PolitiFact, 5/19/2011

- Glenn Kessler, "A bogus chart on Obama and the debt gets a new lease on life", The Fact Checker, 9/29/2011

Reader Response (Added: 2/8/2012): A pseudonymous reader writes:

Just wanted to point out that in the article titled "Mixed-Up Logic Check" regarding debt increase, a further refinement would be the inclusion of inflation adjustment. A 1980 dollar is worth about $2.6 in 2008 according to some of the online calculators, and a 2000 dollar is worth about $1.24 in 2008.I haven't dug deeply into the sources in your article, so I am not quite sure. It looks like Pelosi's office used gross federal debt figures which only goes back to 1993. PolitiFact says it contacted the OMB to get that statistic for years prior to that. My guess would be these are all nominal figures, since there is no mention of a base year or adjustment using the CPI data.

Good catch! I read both the PolitiFact and The Fact Checker articles carefully, but could find no mention of adjusting for inflation. This should have set off a warning bell, since whether inflation is taken into account is an important issue when you're dealing with a span of thirty years. Since I couldn't find any reference to the effects of inflation, I assumed that the debt figures had in fact been adjusted to account for it. I should've known better!

According to PolitiFact, Pelosi's office based the information in the chart on the Treasury's "Debt to the Penny Calculator" (see the Source, below), and PolitiFact also based its own figures on it, some of which I cited above. The calculator page also fails to mention whether it adjusts for inflation, so I sent an email inquiry to the Treasury and received the answer that the results are not adjusted.

So, this is yet another way in which the chart compares apples to oranges, though inflation distorts the results in the opposite direction of the growth of the debt as discussed above. That is, the effects of inflation mean that the earlier the president, the greater the growth of the debt in real terms. However, inflation is not likely to make a significant difference to the comparison of the debt amassed under the previous president and that so far accrued under the current one.

Let this be an object lesson not to assume that figures have been adjusted for inflation when reported by the news media, not even when reported by the "fact checkers".

Sources:

- "The Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It", TreasuryDirect. Note (Added: 11/15/2022): This calculator seems to no longer exist.

- Email from the Office of Public Debt Accounting, the Bureau of the Public Debt, United States Department of the Treasury, 2/6/2012

January 19th, 2012 (Permalink)

Debate Watch

The umpteenth―I've lost count―debate of the candidates for the Republican nomination for President, moderated by journalist Bret Baier, was held in South Carolina a few days ago. The following transcript has been heavily edited to keep it on topic, but also to omit hesitation, repetition, stumbling over words, and one apparent mistranscription (see the Source, below, for the unedited transcript):

Baier: Next round of questions is on foreign policy. And we’ll begin with Congressman [Ron] Paul. In a recent interview, Congressman Paul, with a Des Moines radio station you said you were against the operation that killed Usama bin Laden. You said the U.S. operation that took out the terrorist responsible for killing 3,000 people on American soil, quote, showed no respect for the rule of law, international law. So to be clear, you believe international law should have constrained us from tracking down and killing the man responsible for the most brazen attack on the U.S. since Pearl Harbor?Paul: Obviously no. I did not say that. As a matter of fact, after 9/11 I voted for the authority to go after him. And my frustration was that we didn’t go after him. It took us ten years. We had him trapped at Tora Bora and I thought we should have trapped him there. I even introduced another resolution on the principle of marque and reprisal to keep our eye on target rather than getting involved in nation building.

Paul starts out with a typical "politician's answer", that is, trying to change the subject, which is what politicians do when they're afraid that a direct answer to a question will lose them votes. In this case, Baier asks for Paul's view of the military operation that killed bin Laden last year, but Paul changes the issue to why bin Laden wasn't captured ten years earlier. At first, Paul answers Baier's question "no", and denies having said what Baier reported, but it's not clear exactly what it is Paul is denying―as we'll see, Baier's characterization of his position appears to have been accurate. Then, Paul changes the subject. Baier, however, spots the attempted switcheroo and presses him on the original, unanswered question:

Baier: But no respect for international law was the question about the quote that you used in Des Moines.

Paul: …I don’t see any reason why they couldn’t have done it like they did after Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and that would have been a more proper way. If somebody in this country, say a Chinese dissident come over here, we wouldn’t endorse the idea, well, they can come over here and bomb us and do whatever. I’m just trying to suggest that respect for other nations' sovereignty. …

Baier: Speaker [Newt] Gingrich? If you received, Speaker Gingrich, actionable intelligence about the location of Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar inside Pakistan would you authorize a unilateral operation, much like the one that killed bin Laden, with or without the Pakistani government knowing, even if the consequence was an end to all U.S.-Pakistani cooperation?

Newt Gingrich: Well, let me go back to set the stage as you did awhile ago. Bin Laden plotted deliberately, bombing American embassies, bombing the USS Cole, and killing 3,100 Americans, and his only regret was he didn’t kill more. Now, he’s not a Chinese dissident. You know, the analogy that Congressman Paul used was utterly irrational. A Chinese dissident who comes here seeking freedom is not the same as a terrorist who goes to Pakistan seeking asylum. Furthermore, when you give a country $20 billion, and you learn that they have been hiding―I mean, nobody believes that bin Laden was sitting in a compound in a military city one mile from the national defense university and the Pakistanis didn’t know it.

Here, Gingrich points out, correctly, that Paul's argument is based on a weak analogy. However, while Paul eventually got around to directly answering Baier's question when pressed, Gingrich never did answer Baier's specific question of whether he would order such an operation if the consequence was an end to cooperation with Pakistan.

Sources:

- "TRANSCRIPT: Fox News Channel & Wall Street Journal Debate in South Carolina", Fox News Insider, 1/17/2012

- Nigel Warburton, Thinking from A to Z (Second Edition, 2000), "politician's answer"

Fallacy: Weak Analogy

January 16th, 2012 (Permalink)

Name that Star Fallacy!

Philip Plait from Bad Astronomy on star-naming:

There are companies that offer to sell you the right to name a star after someone―yourself, perhaps, or a loved one or friend. For a fee, and not necessarily a small one, you receive a certificate authenticating some star in the heavens with the name you bestow on it. Some companies even give you the co-ordinates of your star and a stylish map so you can find it. There are many organizations like this, and one thing most have in common is that they strongly imply―and some come right out and say―that this star is now officially named after you. Congratulations!But does that star really have your name? … The answer, of course, is no. … The bottom line is, despite any claims by these companies, the name you give a star is just that: a name you give it. It isn't official and has no validity within the scientific community.

[The website of one of these companies] claims there are 2,873 stars visible to the naked eye; in reality, there are more like 10,000 (depending on sky conditions). Besides being too small, that figure is awfully precise. How do they know it's not 2,872 stars, or 2,880? Using overly precise numbers sounds to me like another way to make them seem more scientific than they really are.

Source: Philip Plait, Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing "Hoax" (2002), p. 242

January 8th, 2012 (Permalink)

Reader Review: Critical Inquiry

It ain't so much the things we don't know that get us into trouble. It's the things we know that just ain't so.―Attributed to Mark Twain

Patricia Heil sends in the following review:

Michael Boylan's Critical Inquiry, first published in 1988 by Prentice Hall, is now in its second edition with Westview. It's short, 191 pages. Short can be good, focused, and organized, with no footnotes but a good bibliography or "further reading" section; another book that I prize very highly is only 192 pages long and has an excellent bibliography. With Critical Inquiry, I had to go through every page to find the ten sources that Boylan quotes in two chapters: three are his own work, and two are the sources of examples of issues involving critical thinking, not background material about logic or fallacies.Boylan claims his work has been used in classrooms for 20 years, which means starting with the first edition. I probably would buy this book only if required to for a class. One reason is the limited sources. I've seen websites with more complete information and a larger set of references.

In chapter 4, Boylan tries to demonstrate the difference between topical and logical outlining for the same sample paragraph. While his examples definitely display different viewpoints about the sample paragraph, they are too extreme; the topical (bad) copies all the emotionally laden negative words and the logical (good) uses more neutral terms. He doesn't explain why a topical outline couldn't use neutral terms. External references would be a great help here, if other authors have discussed this, because they might explain the concept so that I can understand it.

One issue the book doesn't address is evaluating information sources for reliability or adequate detail. I know I had to study that when I was getting my second bachelor's degree. Maybe all colleges nowadays teach source evaluation as a separate course, or the courses using Boylan's book have another book for that.

A chapter on that would have been a good companion to his chapters on worldview and "finding out what you think." The point of argument is to get agreement from somebody. The person wanting agreement has to start with what he currently thinks, but he also has to find out if the facts fit his ideas. What facts he has depends initially on the worldview to which he was exposed in family and social circles, but that should not determine which facts to use in an argument because what "everybody knows" sometimes ain't so (apologies to Mark Twain). It's hard to realize that without knowing whether a fact is useful or something to convince an audience to discredit or ignore.

I can understand a professor publishing his lecture notes, but if he wants to sell them to average readers or non-experts in his field, he needs to show that he has taken advantage of the best the field has to offer, unless he's a household name. And if he presents his own innovation, he needs to convince people by clear and detailed explanations that he's done something useful in the field in general. That's not what I get here.

By the way, I don't think that's Mark Twain Patricia is alluding to. According to Ralph Keyes, the saying traces back to another nineteenth-century American humorist, Josh Billings, who is now almost forgotten, though the way it's usually phrased has been considerably "improved" over time. Apparently, the saying used to be attributed to Will Rogers, a twentieth-century humorist known for such humor, but now less well-remembered than he used to be. Nowadays, the saying seems to have attached itself to Twain, who is a magnet for folksy ("ain't") humor. As a consequence, the saying illustrates its own thesis!

Source: Ralph Keyes, "Nice Guys Finish Seventh": False Phrases, Spurious Sayings, and Familiar Misquotations (1993), p. 74

January 5th, 2012 (Permalink)

Fact Checkers are Sacred

Comment is free, but facts are sacred.―C. P. Scott

James Taranto is back with another criticism of fact-checking. A few years ago, he took a shot at the fact checkers, and I thought it a clear miss (see the Resource, below). This time he hits the mark (see the Source, below). Check it out, it's worth reading.

I agree with most of Taranto's analysis, but there's one major missing piece: he doesn't criticize the whole idea of a "Lie of the Year". I agree with Taranto that the supposed "lie" this year is not really a lie though, in political usage, all that the word "lie" has come to mean is "falsehood". However, even choosing a "Falsehood of the Year" is a bad idea. What's to be said for it, other than it's a good way for PolitiFact to get publicity?

First of all, choosing a "Blank of the Year" is a dubious journalistic practice, since the best that can be said for it is that it makes it easy for reporters to come up with stories at the end of the year: just fill in the blank. Another reason it's a bad idea is that all falsehoods are created equal, and none is more false than another. So, assuming that the claimed "lie" really is false, what makes it special enough to be crowned "Lie of the Year"? The only thing that occurs to me is that the "lie" is thought by someone to be somehow the most significant or important lie of the year.

What's significant or important is a matter of opinion, not a matter of fact. Thus, by choosing a "Lie of the Year", the fact checker has necessarily stepped out of the role of checking facts into the role of commenting upon them. In this way, the "fact checkers" cease to be checkers of fact and become pundits. Not that there's anything wrong with being a pundit, but in the age of Instapundit everybody and his brother is a pundit. Fact-checking is a rare and special thing, or at least it is when it's done right.

Sources:

- C. P. Scott, "Comment is free, but facts are sacred", The Guardian, 11/28/2002

- James Taranto, "Bad-Faith Journalism", Best of the Web Today, 1/3/2012

Resource: Mau-Mauing the Fact Checkers, 10/27/2008

Update (1/7/2012): The Columbia Journalism Review also has an article on fact-checking in its "Campaign Desk" column that's worth reading. Its author, Greg Marx, makes much the same argument that I was trying to make above, but in a longer-winded way. As a result, if you found my treatment too brusque, you might understand his better. He writes:

…[T]he sights of the broader fact-checking movement often seem to be set on something different than strict truth and falsehood. And by acknowledging that, the fact-checkers might grapple with some important questions about the project in which they’re engaged―and might see more clearly the box in which they’ve trapped themselves. …[W]hile the language of fact-checking is powerful, it’s also limited―and the fact-checkers’ tendency to stretch that language beyond its limitations undermines the credibility of their project. One of the problems is that the occasions on which that language is appropriate are less frequent than you might think. …[M]any “fact-checking” pieces actually contain counterarguments―many of which are solid, some shoddy or tendentious, but few of which really fit in a “fact-check” frame.

In other words, the fact checkers aren't always checking facts, and they shouldn't call it "fact checking" when it's not for fear of bringing the whole enterprise into disrepute.

So why have the fact-checkers ventured into uncheckable territory? Kennedy explains it as a simple matter of supply and demand—to keep content flowing to their sites, the operations need to expand their reach beyond clear untruths. There’s probably some truth to that.

Probably so, but there are already plenty of pundits, and once you realize that the "fact checkers" are just pundits who don't want to admit it, they lose their credibility.

I expect that another reason is that fact-checking is dull, hard research work; in comparison, punditry is easy, exciting and glamorous. At magazines or publishers who employ fact checkers, it's usually a low-paying, entry-level position, with no prestige at all. So, who would actually want to be a fact-checker?

…[H]ere’s where the fact-checkers find themselves in a box. They’ve reached for the clear language of truth and falsehood as a moral weapon, a way to invoke ideas of journalists as almost scientific fact-finders. And for some of the statements they scrutinize, those bright-line categories work fine. …[But others] will inevitably involve judgments not only about truth, but about what attacks are fair, what arguments are reasonable, what language is appropriate. And one of the maddening things about the fact-checkers is their unwillingness to acknowledge that many of these decisions…are contestable and, at times, irresolvable. … The argument…is ultimately political, not journalistic, in nature. By insisting otherwise, and acting as if journalistic methods can resolve the argument, the fact-checkers weaken the morally freighted language that’s designed to give their work power….

Because the distinction between fact and opinion is vague, there will always be a danger of the fact-checker sliding over into trying to adjudicate matters of opinion. However, if the fact checkers are to retain any credibility, they need to plant their feet firmly in the factual area and avoid that slide.

Source: Greg Marx, "What the Fact-Checkers Get Wrong", Columbia Journalism Review, 1/5/2012

January 3rd, 2012 (Permalink)

Q&A

Q: I am having difficulty in categorizing one logical fallacy that has come up this fall, and would appreciate your thoughts. When Warren Buffett indicated that he thinks that the rich should bear a heavier portion of the tax burden, many commentators then issued a rebuttal along the lines of, "Well, Mr. Buffett can go ahead and just write a larger check to the IRS," without ever discussing the merits of Mr. Buffett's arguments.

Lately, I've been studying up on "tu quoque", but I don't think it applies here. "Tu quoque" relies on the protagonist (Buffett) in having a (damaging) relationship or involvement with something related to the protagonist's charge, a slight alteration to "unclean hands doctrine". Here, the potential association with the point of discussion is not necessarily a damaging association. To be sure, if Mr. Buffett did write a check it is not in any way damaging to his argument.

How would you classify the dismissal of Mr. Buffett's argument? Maybe it really isn't a logical fallacy, but a dismissive way to move past the topic, treating the argument as if it is not even worth discussing.―Don Shennum

A: This is a complicated question and depends upon the context. If someone simply criticizes Buffett as a hypocrite for not living up to his stated principle, that's no fallacy. Since it's not a logical question, I'll leave it to others to decide how strong such a criticism is.

However, if the context of the attack on Buffett is a criticism of "the Buffett tax", then that is a type of ad hominem argument. I agree with you that it's not a tu quoque―though that is also a type of ad hominem―for the reasons that you give. It's an attack on a prominent advocate of the tax rather than on the tax itself, which makes it ad hominem, but not all ad hominem attacks are fallacious.

However, in this case, Buffett's possible hypocrisy seems irrelevant to the tax issue, as he may well be a hypocrite and the tax still a good idea. If anything, Buffett's hypocrisy may be some evidence in favor of a tax, since it suggests that rich people probably won't contribute money voluntarily. Thus, if we decided that it's necessary to raise more money for the government from the rich, a tax might be the only way to do it.

Therefore, I think the fallacy that you're looking for is argumentum ad hominem.

January 1st, 2012 (Permalink)

Poll Watch

Here are some recent headlines:

Romney Leads in Iowa Poll as Santorum Gains Before State Caucus

Iowa Poll: Romney leads Paul; Santorum surges

Reporters like to cover polls as if they were horse races because races are more dramatic than dull numbers. According to the current coverage, Romney is in the lead as the field rounds the final turn heading towards the Iowa caucus, Paul is running a close second, and Santorum is pulling up on the outside. If a political campaign is like a horse race, then it's a horse race on a foggy morning when you can only catch occasional glimpses of the horses through the fog, and often can't tell which is ahead.

The results of the poll have Romney at 24%, Paul with 22%, Santorum at 15%, and the rest straggling behind. However, the sample for this state poll was smaller than is usual for national polls, so that the margin of error is a larger-than-usual four percentage points. As a result, Romney and Paul are really too close to call.

The claim that Santorum is gaining is based on the last two days of the poll which had Romney still at 24%, but Santorum taking second place at 21%, and Paul falling to 18%. However, since this is based on only half of the poll's total sample, the margin of error is an even higher 5.6 percentage points. So, it's possible that Santorum's swapping of places with Paul is just the result of chance rather than a supposed "surge". In any case, we'll soon find out, as the caucus is Tuesday.

Sources:

- John McCormick & Kristin Jensen, "Romney Leads in Iowa Poll as Santorum Gains Before State Caucus", Bloomberg Businessweek, 1/1/2012

- Des Moines Register, "Iowa Poll: Romney leads Paul; Santorum surges", USA Today, 12/31/2011

Resource: How to Read a Poll

Update (1/2/2012): Slate has a cute little animation showing the Iowa polls as a horse race. Unfortunately, there's no fog.

Source: Will Oremus, "The Iowa Horse Race", Slate, 1/2/2012

Update (1/4/2012): It appears that the Santorum surge was real, as Romney won the caucus by only eight votes, and both had 24.6% of the votes cast, while Paul came in third with 21%. Except for Santorum, this is very close to the poll results discussed above.

Source: Jeff Zeleny, "Romney Wins Iowa Caucus by 8 Votes", The New York Times, 1/3/2012