Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

WEBLOG

February 28th, 2022 (Permalink)

Putin, Trudeau & Jewish Nazis

The biggest news in the last week is, of course, Russia invading Ukraine. The dictator of Russia, Vladimir Putin, is attempting to justify the invasion by accusing the Ukrainians of being neo-Nazis. This month's Recommended Reading will focus on Putin's propaganda, together with disturbingly similar rhetoric from closer to home.

- David K. Li, Jonathan Allen & Corky Siemaszko, "Putin using false 'Nazi' narrative to justify Russia's attack on Ukraine, experts say", NBC News, 2/24/2022.

Russian President Vladimir Putin on Thursday peddled accusations of Nazi elements within Ukraine to justify the attack on his western neighbor, a move that experts slammed as slanderous and false. In announcing he had launched Russian forces against key Ukrainian military and logistics posts, Putin said he's striving for "the demilitarization and denazification of" the sovereign democracy in Kyiv. Putin has long sought to falsely paint Ukraine as a Nazi hotbed, which is a particularly jarring accusation given that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is Jewish and lost three family members in the Holocaust. …

Putin hopes to touch upon generations-old scars left from World War II―when an estimated 24 million Soviet citizens died―and conflate modern Ukraine with elements of its problematic past. During World War II, some Ukrainian nationalists fought with the Nazis, battled the Polish underground and helped the Germans round up Jewish citizens for genocide. Ukrainian collaborators were among Nazi forces that put down the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising.

However, in today's Ukraine, the remaining pro-Nazi movement is far from an open, influential force. …[T]here is no evidence to suggest widespread support for such extreme-right nationalism in the government, military or electorate. In the most recent Ukrainian parliamentary elections in 2019, a coalition of ultranationalist right-wing parties failed to win even a single seat in the Rada, the country's 450-member legislature. …

David Harris, CEO of the American Jewish Committee, an advocacy group, said he's confident that Putin's Nazi narrative "won't work. … And…the ones behaving like Nazis are, let's be clear, Putin and his regime. Brazenly invading another country, invoking fake grievances, lying incessantly and denying another nation's right to chart its own destiny are all, yes, taken from the Nazi playbook."

More specifically, it's practically a replay of Nazi Germany's invasion of Czechoslovakia1, except that the current invasion is not going as well for Russia as the earlier one did for Germany.

- Miriam Berger, "Putin says he will ‘denazify’ Ukraine. Here’s the history behind that claim.", The Washington Post, 2/25/2022. Ellipses within quotation marks are in the original.

Russian President Vladimir Putin invoked the Nazis on Thursday when he announced his decision to launch a large-scale military operation in Ukraine. The Russian leader said that one of the goals of the offensive was to “denazify” the country, part of a long-running effort by Putin to delegitimize Ukrainian nationalism and sell the incursion to his constituency at home. The rhetoric around fighting fascism resonates deeply in Russia, which made tremendous sacrifices battling Nazi Germany in World War II. Critics say that Putin is exploiting the trauma of the war and twisting history for his own interests. …

“When Putin was growing up, the Second World War was at the center of Soviet identity and the enemies were the fascists,” said Timothy Snyder, a professor of history at Yale University. The irony now, Snyder said, is that Putin appears to be “fighting a war the way that actual Nazis did,” invading neighbors on the pretext that their borders are irrelevant.

But Putin’s attempt to recast Ukraine’s government as fascist drew widespread condemnation Thursday, including from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who is both Jewish and had family members die in the Holocaust. Three of Zelensky’s great uncles were executed as part of the German-led genocide of European Jews during the war, the president said on a trip to Jerusalem in 2020. His grandfather, who was the brother of those killed, survived. “Forty years later, his grandson became president,” Zelenksy said in an address. The Ukrainian leader also fired back at Putin’s Nazi claim Thursday, saying on Twitter that Russia had attacked Ukraine just “as Nazi Germany did.” …

According to Michael McFaul, a former U.S. Ambassador to Russia, “there is a history of some Ukrainians fighting on the Nazi side…but a very small group.” … Now Putin is trying to paint Zelensky’s government as “Nazis supported by NATO,” McFaul said. According to Putin, he must fight to save the Russian-speaking community in eastern Ukraine. In his speech announcing the start of the operation, he said that the “goal is to protect the people who are subjected to abuse, genocide from the Kyiv regime. To this end, we will seek to demilitarize and denazify Ukraine and put to justice those that committed numerous bloody crimes against peaceful people, including Russian nationals,” Putin said, according to Russia’s state news agency.

His language is also a red flag that he intends to overthrow the government in Kyiv, said Sergey Radchenko, a professor of international relations at Johns Hopkins University. The Kremlin has long tried to “present the whole idea of Ukrainian nationalism as a neo-Nazi movement,” he said, adding that the narrative is historically false. Following Putin’s logic, Radchenko said, Russia’s end goal in Ukraine could be to rid its government of “Ukrainian nationalists…who in their eyes are Nazis.”

At the same time, Snyder said, Putin’s moves to label Ukraine’s government as fascist are “completely emptied of any specificity.” During the Cold War, the term came to apply to anyone in the West or those who opposed Russia, he said. “Anyone can be a fascist” in Russian propaganda, Snyder said….

And in Canadian propaganda, too, as we'll see. George Orwell pointed out in 1944 that the word "fascist" was already "almost entirely meaningless"2. "Fascist" is now a loaded word, like "weed", that has little descriptive meaning: a "weed" is just a plant that we don't like or is where we don't want it. For Putin, "fascists" are people he doesn't like who are where he doesn't want them, namely, Ukraine.

What the above articles fail to mention is that when the Nazis invaded the Ukraine, which was part of the Soviet Union at the time, it was less than ten years after the communists had knowingly starved millions of Ukrainians to death3. Unsurprisingly, some Ukrainians at first greeted the invading Germans as liberators freeing the Ukraine from a murderous communist tyranny, though the reality was that they were being invaded by a murderous fascist tyranny.

Unlike Putin, Justin Trudeau is not a dictator, at least not yet. Just as Putin suggested that Ukraine's Jewish president is a supporter of Nazis, Trudeau has accused a Jewish member of Canada's House of Commons of being on the side of Nazis for questioning his invocation of the Emergencies Act in order to suppress peaceful protests of his policies.

- Brian Lilley, "Trudeau linking Lantsman to swastikas is disgusting", Ottawa Sun, 2/17/2022.

It’s become far too common for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to denounce anyone he disagrees with as a racist, misogynist or even a Nazi but that he did so to a Jewish woman on Wednesday is outrageous. Yet there was Trudeau, responding to a completely reasonable question by linking Conservative MP Melissa Lantsman to people waving Nazi flags. … Lantsman was questioning the government on their decision to invoke the Emergencies Act, a serious move, one that no government has ever contemplated. …

“Conservative Party members can stand with people who wave swastikas, they can stand with people who wave the Confederate flag, we will choose to stand with Canadians,4” Trudeau said. Trudeau knew who he was speaking to. He knows who Melissa Lantsman is and that she is not only Jewish herself but also represents the riding with the biggest Jewish population in the country. Maybe he didn’t know that she was the descendent of Holocaust survivors but that hardly matters. Trudeau knew enough to know better. Lantsman raised a point of order in the House of Commons asking Trudeau for an apology but he had already left the House. “I did not get that apology,” Lantsman told me when I spoke to her Thursday. …

What’s bizarre is that while the Liberals keep seeing Nazis all over the protests in Ottawa, not a single Conservative MP has…stood with anyone carrying such a flag. There has been exactly one swastika flag seen in Ottawa and that was on the first day and the person never made it to the protest site. They were chased away. … Trudeau owes Lantsman an apology, he owes Canada a serious response to the crisis he helped create.

He should apologize not just to Lantsman but to the mostly peaceful protesters that he smeared―in this case, they were truly mostly peaceful as opposed to the "mostly peaceful" protesters who burned and looted American cities in 2020. Whatever you think of their goals, they committed no looting, arson, or violence against the police or innocent bystanders in pursuit of those goals. In other words, they used traditional democratic means of protest, rather than the violence and terrorism which are the typical tactics of fascists.

What were the crimes committed by these protesters? According to the Associated Press, "Police in Canada’s capital are investigating possible criminal charges after anti-vaccine protesters urinated on the National War Memorial, danced on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and used the statue of Canadian hero Terry Fox to display an anti-vaccine statement.5" So, public urination, unauthorized dancing, and misuse of a statue. One of the organizers of the protests has been arrested and denied bail for "counseling to commit mischief"6. These are crimes in Canada? Well, public urination, okay.

It's also clear from the photographs of the protesters that, with one possible exception, they were not carrying pro-Nazi flags7. Rather, swastikas were added to flags or signs as a way of linking Trudeau to the Nazis. If Trudeau had complained that some of the protesters had falsely accused him of acting like a Nazi, he'd have my complete sympathy. Instead, he proceeded to act in a way that made the protesters' accusations seem plausible. Obviously, Trudeau's shameful behavior is small potatoes compared to Putin's, but it's remarkable how similar their rhetoric is.

Notes:

- Michael E. Ruane, "Putin’s attack on Ukraine echoes Hitler’s takeover of Czechoslovakia", The Washington Post, 2/24/2022

- George Orwell, "What is Fascism?", Tribune, 1944

- Patrick J. Kiger, "How Joseph Stalin Starved Millions in the Ukrainian Famine", History, 4/16/2019

- I've edited this quote based on the following article: Kenneth Garger, "Justin Trudeau sparks outrage after accusing Jewish conservatives of supporting swastikas", New York Post, 2/16/2022

- "Ottawa Police Investigating Some Anti Vaccine Protesters", Associated Press, 1/30/2022

- Lora Korpar, "Freedom Convoy Leader Tamara Lich Denied Bail After Arrest in Ottawa", Newsweek, 2/22/2022

- Jordan Liles, "Swastikas and Confederate Flags Seen at Canada’s ‘Freedom Convoy’", Snopes, 2/17/2022

Disclaimer: I don't necessarily agree with everything in these articles, but I think they're worth reading as a whole.

February 21st, 2022 (Permalink)

A Tendentious Top Ten

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine against COVID-19 was not approved for use in children under the age of twelve until October 29th of last year, when it was approved for those aged 5-11 in a reduced dosage1. At a press conference a couple of days earlier, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Rochelle Walensky, said the following:

Understanding where we are in the current state of the pandemic allows us to look forward to what is on the horizon and to be clear in our efforts…. This includes protecting our children and understanding the risk that COVID-19 poses to them. The health and wellbeing of our nation’s children is of the utmost importance. …[T]he regulatory process is underway to make COVID-19 vaccines available for children ages 5 to 11. And I’d like to just step back and take a moment to put some of this into perspective. CDC’s data presented at yesterday’s FDA Advisory Committee showed that among all children ages 5 to 11, COVID-19 was one of the top 10 causes of death in the United States over the last year.2

Why did Walensky make this "top ten" claim? As mentioned above, she made it during a press conference anticipating the approval of the vaccine for children of that age range. That COVID-19 was in the top ten causes of death for young children sounds as though a lot of children must have died from it. So, the point was to alarm parents about the threat of COVID-19 enough to have their children vaccinated as soon as the vaccine was approved.

Unsurprisingly, some news media parroted Walensky's alarming claim without any skepticism or apparent fact-checking3. However, skepticism of the claim is warranted: one thing that is known about COVID-19, and has been known since early in 2020, is that it discriminates based on age. The older you are, the more likely it is to kill you, and very young children are at minimal risk of death4.

Before we look at the top ten list in depth, let's ask a few preliminary critical questions about it. Suppose that COVID-19 were among the top five causes, would Walensky have said that it was in the top ten? Probably not, so we can conclude that the disease must be at number six at the highest on the list, and it might even be as low as ten5. So, that means that there are at least five causes that kill more children than COVID-19. Thankfully, young children who survive infancy are usually healthy and rarely die of diseases, so what are five causes that kill them at numbers greater than COVID-19? An obvious one is accidents, especially car accidents, but also accidental drownings and accidents in the home, such as fires. It's difficult to think of any diseases that kill a large number of young children, at least in the United States.

This thought raises another question: how are these different causes categorized? For instance, given that a large proportion of child deaths occur in accidents, will there be a single category of "Accidental Deaths", or would the category be broken down into "Automobile Accidents", "Accidents in the Home", or other more specific categories, such as "Accidental Drowning" or "Death in a Fire"? How fine-grained the analysis is will affect how far down the list COVID-19 ends up. So, a little critical thought shows that we should not be too alarmed by the top ten claim until we look into the details of the list of causes―let's do that now.

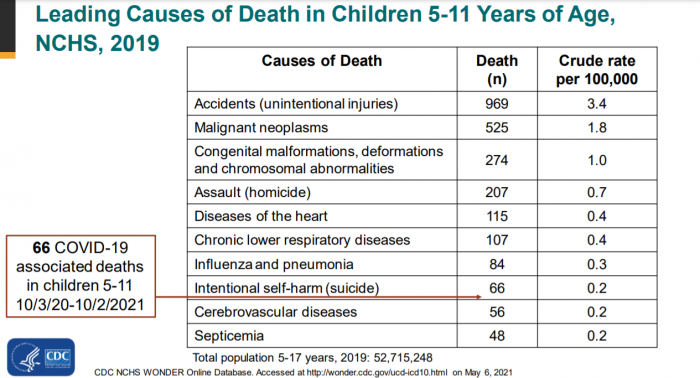

Apparently, the claim was based on the following table that was presented in the committee meeting that Walensky referred to6:

The table shows the ten "leading" causes of death for children from five to eleven for 2019, that is, prior to COVID-19. The COVID-19 "associated" deaths for children of the same age for the year from the beginning of October 2020 to the same time in 2021, just prior to this table being prepared, tied with the eighth leading cause of death. As you can see, the cause of death it tied with is―yikes!―suicide. You read that right: suicide in children less than twelve years old. So, COVID-19 killed in a year's time as many children as committed suicide in 2019. Thankfully, this was only 66 children, or one in a half-million―see the crude rate in the table.

Of course, every death of a young child is a tragedy, but the death of a young child by suicide is especially tragic since it should be preventable. It's only common sense that many of the steps that have been taken during the epidemic―such as school closures, distance learning, and mask wearing―are likely to harm the mental health of children. Moreover, there is already evidence of such harmful effects: for instance, emergency room visits for mental health problems increased by 24% for children 5-11 years old in the latter part of 2020 as compared to 20197.

Another factor, which is not explicitly represented in the top ten chart, is the effects of drug abuse. Deaths from overdoses of illegal drugs have increased over the last two years8. How much of this increase is due to the social and economic effects of the reaction to the epidemic is impossible to say, but it is surely not zero. Now, you wouldn't expect 5-11 year olds to die from drug overdoses, but you also wouldn't expect them to commit suicide. There is no separate category in the chart for drug deaths, so where would they fit: perhaps under "Accidents"? Or, were there so few that they would not be considered a "leading" cause of death?

I point this out because the chart makes no effort to quantify the number of deaths due to the effects of our social and economic reaction to COVID-19 on the mental health of children. Did more children die from those effects than died from COVID-19? From this chart, we simply can't tell.

To be fair to Walensky, immunization against COVID-19 probably has little if any direct effect on suicide or drug abuse among children. However, fomenting fear that COVID-19 threatens young children may contribute to the social hysteria that leads to schools being closed, children being isolated from friends and family, or forced to wear masks for long periods of time. Such actions are not good for the mental health of children, or adults for that matter.

Good intentions do not excuse presenting misleading claims aimed at scaring people into doing something even if it is the right thing to do. Walensky's top ten claim is typical of so much of public communication by government health officials: it's not an outright lie, but it is a half-truth intended to manipulate people into taking the action desired by the government. I hate to say it, but Walensky and other public health officials seem not to trust the American people with the truth. It's hard to see why the American people should trust them in return9.

Notes:

- "FDA Authorizes Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Emergency Use in Children 5 through 11 Years of Age", U. S. Food & Drug Administration, 10/29/2021

- "Press Briefing by White House COVID-19 Response Team and Public Health Officials", The White House, 10/27/2021

- For instance:

- Lauren Jackson, "Covid Among Top 10 Causes Of Death Among Children Aged 5-11 In US", AFX News, 10/28/2021

- Corey Jones, "Watch Now: Virus is now among top-10 leading causes of death in children; vaccine is approved for kids 5-11", Tulsa World, 11/3/2021

A couple of exceptions at least offered some context rather than just repeating Walensky's claim:

- Susan Jones, "CDC: 94 Children Ages 5-11 Have Died of COVID; 0.00012% of All COVID Deaths", CNS News, 10/26/2021

- Patrick Phillips, "COVID now 6th-leading cause of death in kids 5-11, SC Health Dept. says", WCSC, 11/3/2021.

- German Lopez, "How the risk of Covid-19 for kids compares to other dangers", Vox, 10/7/2021

- This is an application of Paul Grice's first conversational maxim of quantity, which enjoins one to be as informative as possible; see: Paul Grice, "Logic and Conversation", in Studies in the Way of Words (1989), p. 26

- Fiona Havers, "Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Children Aged 5–11 years", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 10/26/2021

- Rebecca T. Leeb, et al., "Mental Health–Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children Aged <18 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, January 1–October 17, 2020", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 11/13/2020

- "Overdose Deaths Accelerating During COVID-19", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 12/18/2020

- Michael S. Pollard & Lois M. Davis, "Decline in Trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention During the COVID-19 Pandemic", RAND Corporation, 2021

February 12th, 2022 (Permalink)

The Absent-Minded Professors

As I mentioned in a previous account of a meeting at the New Logicians' Club*, Professor Knight, one of its members, was notoriously absent-minded. At the most recent meeting, Knight suddenly arose from the table he shared with three other professors and dashed for the door. Apparently, he had just remembered some other appointment, as he was wont to do. Since it was cold outside, everyone had worn a coat and hat to the meeting, and these articles of apparel were hanging from a row of hooks near the entrance. In his rush, Knight grabbed a coat belonging to one of the other members at his table, and a hat belonging to a different table-mate.

As a result of Knight's mistake, when the time came for the other three members to leave, no one got the right coat and hat. In fact, each of the four members ended up with one of the other four's coat, and a hat belonging to yet another.

For some reason, Professor Knight called me up when he discovered his error. "I accidently took Professor X's hat!" he told me. "I recognize it because it's an odd-looking hat, which is probably why I grabbed it, but I don't know whose coat I got―it's certainly not mine!" As mentioned previously, Knight is an unusually honest fellow, so you can trust what he said to be true.

I promised Knight to investigate the incident and try to determine who got whose hat and coat, and arrange to return them to their rightful owners. My investigation revealed only one further clue: Professor Y's coat had been taken by the same professor who had taken Professor Z's hat.

Can you help me solve the mystery of the mixed-up hats and coats? Whose hat and whose coat had each of the four professors taken?

| Professor | Coat | Hat |

|---|---|---|

| Knight | Z | X |

| X | Y | Z |

| Y | X | Knight |

| Z | Knight | Y |

Explanation: Since Knight took X's hat, he could not have also taken X's coat. Thus, he must have taken either Y's or Z's coat. However, we know that one of the four professors took Y's coat and Z's hat. Since Knight took X's hat, he's not the one who took Y's coat. Therefore, he took Z's coat. That's one down.

Since none of Y, Z, or Knight could be the one who took Y's coat and Z's hat, by a process of elimination we know that X must be the one who did so. Two down: we're halfway there!

X's and Z's hats are already accounted for, so Y must have taken Knight's hat. That means that Y could not have also taken Knight's coat, and since Z's coat is accounted for, Y must have taken X's coat. We're almost done!

Only Z is left, and only Knight's coat and Y's hat are unaccounted for, so Z must have taken them. We're done!

Disclaimer & Disclosure: This puzzle is based on one from: J. A. H. Hunter & Joseph S. Madachy, Mathematical Diversions (1975), pp. 108 & 151. Oddly, the puzzle contains an unnecessary clue that I've omitted in the above. Perhaps the clue was added just to confuse the reader, but then it was used in the solution, which made the solution more complicated than needed. So, the above is a simplified version, but I hope still sufficiently puzzling to be interesting.

Also, eleven years ago I gave a similar puzzle based on the one from Hunter & Madachy, but with a different set of clues; see: The Puzzle of the Absent-Minded Professors, 2/4/2011.

*Christmas at the New Logicians' Club, 12/25/2021

February 4th, 2022 (Permalink)

Credibility Checking, Part 2: Divide & Conquer

Part 11 of this series on credibility checking dealt with how to use what you know to compare and contrast with what you don't know in order to check factual claims for credibility. This part concerns how to cut big numbers down to size so that they can be easily evaluated.

Big Numbers

Many of the factual claims that you meet involve numbers, and many of those numbers will be large. This is because politicians, activists, reporters, and advertisers love big numbers. What better way to get you excited enough about something to take action, whether it is voting for a candidate, writing a check to a charity, or buying a product, than to impress you with a big number. The news media and advertisers love big numbers because they attract people's attention, and attention is money.

Unfortunately, very large numbers are often beyond our ability to understand or put into perspective, since most of us have little if any experience with them. Big numbers can cause "number numbness"2, which is the lack of a sense of their comparative magnitudes: millions, billions, trillions are all just "really big". From the standpoint of those who use big numbers to manipulate you, number numbness is a good thing since it prevents you from skeptically evaluating their claims.

Another Example

Last month, we examined in detail an example of the use of a big number by activists and politicians to alarm Americans about abducted children3. Let's look at an example where an even larger number was used to concern people about a different social problem.

A book published in 1991 claimed: "Each year, according to the association, 150,000 American women die of anorexia.4" 150,000 is a big number, especially in the context of anorexia deaths, but is it a credible number? The book claimed that the source of the number was the American Anorexia and Bulimia Association, which seems to be a credible source that ought to know.

In Part 1, we checked the credibility of the factual claim that 50,000 American children had been kidnapped by strangers in 1982. 50K is a big number, at least in the context of kidnapped children, and we compared and contrasted it with a number of the same order of magnitude (OoM), finding it implausible. 150K is, of course, three times larger and we could apply the same analysis to it, finding it three times as implausible. However, in this part, I want to use the new example to demonstrate a new technique.

As we saw in Part 1, you already know a lot, perhaps more than you realize. While you probably don't know the number of women who die from anorexia each year, you probably do have some idea of the number of people who die in car crashes, or the population of the country, or some other fact that can be put to use. Similarly, while you probably don't know the national statistic, you're more likely to have a sense of the size of the problem in your own state or local community. The problem is to bring what you know to bear on the big number by cutting it down to size.

Dividing

How can you make a number that is too large to grasp easier to understand? Make it smaller. One technique to do so is to use division; of course, you have to find some appropriate way of dividing the number up into smaller numbers.

One reason that the number of supposed anorexic deaths is so big is that it's for the entire country. You can divide statistics for the entire nation by fifty in order to get the approximate number in your state, assuming that you live in the United States. In the case of the example, you can do this in your head: divide 150K by 50 to get 3K. Is it believable that three thousand women die annually of anorexia in your state?

We're not done dividing yet, since there's another dimension that we can use to divide: time. Since, according to the claim we're checking, there are an average of 3K women who die of anorexia in your state each year, we can divide by 365―a landmark number5 that we all know. This is another calculation that you can do in your head: the number of days in the year is approximately 300, which is one-tenth of 3K, which means about ten deaths a day. More precisely, the result of dividing 3K by 365 is slightly more than eight, but keep in mind that a ballpark estimate is all that we need.

Conquering

Now, having divided the big number in about every way that makes sense, you're in a position to apply what you know to it. Is it plausible that eight or ten women die every day in your state from anorexia? Have you seen reports in your state's news media about an epidemic of anorexic deaths? I can't answer these questions for you, but I can say that it is highly implausible that there could be so many deaths in my state without my having heard a word about it.

Dividing and conquering suggests that the factual claim that 150K American women die each year from anorexia is quite implausible. As we saw in Part 1, the number of Americans of all ages and both sexes who die in automobile accidents yearly is around 30-35K, that is, four to five times less than the supposed number who die from anorexia, which would mean that anorexia was four to five times worse a problem than traffic fatalities, at least in terms of deaths. I find it hard to believe that such a large problem would receive so little attention.

Of course, sometimes surprisingly implausible claims are true. Keep in mind that the point of a credibility check is not to decide whether a factual claim is true or false, but to decide whether it is worth fact checking. This example clearly is worth checking.

Fact Check

Thankfully, I don't need to do a full fact check of this claim since I did one ten years ago6: check it out if you want the full details. The gist is that the actual number of anorexia deaths per year in the United States is in the tens or hundreds, not tens or hundreds of thousands. Thus, the claim was wrong by three or four OoMs.

I hope that this entry convinces you not to be intimidated by large numbers, since now you know how to cut them down to size. Also, you shouldn't be discouraged by your own ignorance. Before reading this entry, you probably didn't know even approximately how many people die of anorexia each year. However, you do know many things that you can use to check the credibility of claims about what you don't know.

As we've seen, you can't always trust claims made by politicians, activists, or books, so the next time you come across such a claim that uses a big number, divide and conquer!

Notes:

- Credibility Checking, Part 1: Compare & Contrast, 1/7/2022.

- Douglas R. Hofstadter, "On Number Numbness", Metamagical Themas (1985), pp. 115-135.

- The Goldilocks Number, 1/23/2022.

- Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women (1991), pp. 181-182.

- A landmark number is one that helps you find your way around the data landscape and is, therefore, worth remembering.

- Be your own fact checker!, 2/15/2012

February 2nd, 2022 (Permalink)

Tenet or Tenant?

I recently came across an example of the word "tenant" used in place of "tenet", but I haven't been able to find it again. It reminded me that I had seen previous cases in which the two words were confused. Here's one I was able to find in an abstract of a paper published in a medical journal: "Although the pathophysiology of edema varies, compression therapy is a basic tenant of treatment, vital to reducing swelling.1"

"Tenet" and "tenant" are similarly spelled, and their pronunciations are even similar, especially when people don't enunciate clearly. Yet, the two words are very different in meaning, though both are nouns. A "tenant" is someone who rents a place, whether an apartment or farmland2, whereas a "tenet" is a principle or axiom of a religion or other system of belief3. Because of their similar spelling and pronunciation, "tenant" is occasionally written when "tenet" is meant, as in the above example. The mistake seems to seldom if ever go in the opposite direction, perhaps because "tenet" is a less familiar word, and I don't recall ever seeing "tenet" in place of "tenant".

For another possible example, the online Cambridge Dictionary supplies the following as an example of the use of the word "tenant": "Not entirely unexpectedly, the articulation by some of self-concept/image entailed express or implied criticisms of tenants.2" It's a confusing sentence, and the dictionary does not supply a citation or any further context that might help to clarify it. Still, to the extent that it makes any sense at all taken out of context, it seems to make more sense if we suppose that "tenets" was meant in place of "tenants". If so, this is not an example of the use of the word "tenant", but of its misuse.

Somewhat to my surprise, none of the reference works I usually consult discuss the confusion of "tenant" for "tenet", which suggests that it isn't such a common mistake. However, the online Merriam-Webster dictionary does have a page about it, and supplies a couple of clearer examples4.

Given that both words are English nouns, it's unlikely that a spell-checker or even a grammar-checker will catch the substitution of one for the other. I tried one or more examples in my old copy of Microsoft Word, and an online grammar-checker, neither of which noticed any problems with them.

One of the basic tenets of the use of spell- and grammar-checking programs is that they will catch most mundane typographical errors, freeing up your memory for the kind of mistakes that the programs themselves won't prevent. So, file the difference between "tenet" and "tenant" in your mental spell-checker.

Notes:

- N. Stout, et al., "Chronic edema of the lower extremities: international consensus recommendations for compression therapy clinical research trials", Int Angiol., 2012 Aug;31(4):316-29.

- "Tenant", Cambridge Dictionary, accessed: 2/2/2022.

- "Tenet", Cambridge Dictionary, accessed: 2/2/2022.

- "On 'Tenant' vs. 'Tenet'", Merriam-Webster, accessed: 2/2/2022.