WEBLOG

Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

August 30th, 2007 (Permalink)

Headline

Count claims cross found in trash

Dracula?

Source: "Count claims $500,000 cross found in trash", Associated Press, 8/22/2007

August 29th, 2007 (Permalink)

Name that Fallacy!

In the latest and apparently the last of the Harry Potter books, a character named "Hermione" does a good job of explaining what's wrong with a certain type of argument:

"How can I possibly prove it doesn’t exist? Do you expect me to get hold of―of all the pebbles in the world and test them? I mean, you could claim that anything’s real if the only basis for believing in it is that nobody’s proved it doesn’t exist."

Source: Christopher Hitchens, "The Boy Who Lived", New York Times, 8/12/2007

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Pete Wallace.

August 27th, 2007 (Permalink)

Fallacy Files Book Club: Unspeak, Chapter 1, Part 2

I have a few comments about the last part of the first chapter of Steven Poole's Unspeak―the part that is not included in the online extract, so you'll have to find a hard copy if you want to read along:

- Poole gives the phrase "Coalition of the Willing" as an example of unspeak:

…[W]hen newspapers and TV stations adopted the phrase 'Coalition of the Willing', or even just the shorthand 'coalition', to describe the March 2003 invasion of Iraq conducted overwhelmingly by US and British forces, they quietly endorsed the idea that this was a far-reaching alliance which only a few obstreperous or sulky nations opposed. In fact the countries that opposed the war, such as Germany and France, did not lack conviction; it was just that they were willing to do something else, for instance to allow weapons inspections to continue. The term 'coalition' also helpfully called to mind the far wider and more robust UN-authorised coalition that had gone to war against Saddam Hussein in 1991. (P. 7)

I suppose that "Coalition of the Willing" does fit Poole's definition, but he misses the most remarkable aspect of it, which is what a poor piece of unspeak it is. The reference to "the willing" immediately calls to mind the fact that there were some prominent nations who were unwilling to support the invasion, or at least to publicly acknowledge their support. Moreover, the phrase was probably intended as a response to criticisms that the Bush administration was bribing and twisting the arms of nations to get them to support the invasion. However, the reference to "the willing" would serve to remind people of these criticisms, which is probably why the phrase seems to have been quickly and quietly dropped.

The focus of Poole's criticism is on the word "coalition", but while it's true that the Gulf War had broader support, the Iraq war was fought by a coalition led by the United States. Even if it had been just the U.S. and the U.K., that is still a coalition. As in the law of libel so it must be in unspeak: the truth is an absolute defense. Of course, it's also fair to point out in either case the predominant role played by the U.S. in that coalition. I hope that this isn't an indication of the quality of Poole's analysis in the rest of the book.

- Poole has a short section (pp. 9-10) on the phrase "public diplomacy", which he takes to be unspeak for "propaganda". However, the word "propaganda" is a loaded term that refers only to dishonest or misleading communication. For this reason, one can't expect anyone―especially a propagandist!―to refer to what they do as "propaganda". Mostly, the word is used―often by propagandists―to refer to the public communications of their political opponents.

It was not always so. The word "propaganda" is Latin in origin, but it's modern sense is derived from the Vatican's Congregatio Propaganda de Fide, that is, the "congregation for the propagation of the faith", which was the evangelizing arm of the Catholic Church. So, the original sense of the word "propaganda" was not negative, but referred to any organized attempt to spread an idea. For instance, the department that Josef Goebbels headed was called the "Ministry for People's Enlightenment and Propaganda". Today, because it has been tainted by association with the Nazis and Communists, no propagandist would use the word "propaganda" in this way. To do so would be bad propaganda!

For this reason, "public diplomacy" may be used sometimes as a euphemism for "propaganda", but then it would be doublespeak rather than unspeak. However, a euphemism is only doublespeak when it is used to conceal something important. A group that communicates honestly with the public can't be expected to call what it does "propaganda". To do so would not be honest!

This doesn't mean that the phrase "public diplomacy" is unobjectionable. It's objectionably vague―but so is "public relations", which is the main alternative. As far as I know, there is no English term that means the same as "propaganda" but lacks its negative connotation. This is why I seldom use the term "propaganda" in the Fallacy Files, except when it has been justified by previous evidence of dishonesty, for to use it without such evidence is question-begging. There is thus a need for a neutral English term for communication by governments, businesses, or political groups, aimed at the general public. Until something better gains currency, we're stuck with "public diplomacy" or "public relations".

Near the end of the chapter Poole writes: "Naturally, in such a book, it is impossible that I will not myself have committed various acts of Unspeak. I leave it as an exercise for the interested reader to identify them." Why wouldn't it be possible, even easy, for him to avoid using unspeak? The word "propaganda" doesn't seem to fit the definition of "unspeak", but it looks as though that definition is already undergoing some stretching, perhaps enough to include propaganda as a type of unspeak. If so, I'm tempted to accept his challenge by identifying the section on propaganda as itself unspeak!

- At the end of the chapter, Poole writes:

…[T]he reader may wish to leap in, with an apposite question: 'Who are you to write such a book?' That is easy to answer in the negative. I am not a linguist; nor am I a political reporter. I claim no authority or expertise beyond a habit of close reading, practised in literary journalism. If the book has some interest, however, it may be simply that it demonstrates that you don't have to be a specialist to resist the tide of Unspeak: you just have to pay attention.

This is refreshingly forthright, though if I weren't so interested in the topic it might discourage me from finishing the book. I agree with Poole that it shouldn't require a specialist to resist unspeak, but that doesn't mean that it may not require a specialist to teach the non-specialist how to resist unspeak. If Poole were a linguist, logician, philosopher, psychologist, or rhetorician, I would have more confidence that I'm going to actually learn something from the rest of the book.

Sources:

- William & Mary Morris, Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins, Volume 1 (1962).

- Steven Poole, "Introduction", Unspeak (2006)

Previous Installment of the Book Club: Chapter 1, Part 1

August 23rd, 2007 (Permalink)

Triplespeak

Annenberg Political Fact Check has a new report out on a political ad that contains three contextomies. According to Fact Check, the organization responsible for the ad is called "Americans Against Escalation in Iraq", but the end of the ad says: "Paid for by the Campaign to Defend America." I don't know what the relationship is between the AAEI and the CDA, but "Campaign to Defend America" is an egregious example of both doublespeak and unspeak, whereas "Americans Against Escalation in Iraq" is a nicely clear name: you can tell from the name alone what the AAEI is all about, but the CDA's aims are concealed by its name. "Campaign to Defend America" is Orwellian doublespeak because it's so imprecise that it could be used by many types of political campaign: for instance, it could easily be the name of a movement against illegal immigration. At the same time, it's unspeak because it begs the question of whether opposing escalation in Iraq is a way of defending America.

When doublespeak and unspeak are combined in this way, perhaps the result should be called "triplespeak".

Source: Justin Bank, "Liberal Lobby Lacks Context", Annenberg Political Fact Check, 8/23/2007

Resources:

- Steven Poole, Unspeak (2006)

- George Orwell, "Politics and the English Language"

August 16th, 2007 (Permalink)

Lessons in Logic 8: Complex Arguments

The examples of arguments given so far in these lessons have consisted of simple arguments without confusing non-argumentative context. Such examples are like training wheels for learning to ride a bicycle. Real-life arguments come surrounded by non-arguments, which is one reason why you need to learn how to recognize arguments and differentiate them from non-arguments, such as descriptions. It's only in lessons such as these that arguments will be helpfully removed from context. Eventually, you have to take the training wheels off.

One aspect of the complexity of argumentation is that real-life arguments are often connected. For instance, the conclusion of one argument may be the premiss of another. In this way, a series of arguments may be linked together in a chain.

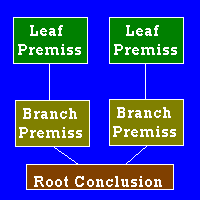

More commonly, arguments are connected in a tree-like structure: since an argument may have two or more premisses, these premisses may be conclusions of further arguments, and the premisses of these further arguments may themselves be conclusions in still more arguments. This branching may go on indefinitely, though of course any real-life argument will have finite branches. Here's some terminology that's useful for talking about complex arguments:

- Leaf Premiss: A premiss which is not the conclusion of an argument in the tree.

- Branch Premiss: A premiss which is also the conclusion of an argument in the tree.

Alias: "Intermediate Conclusion". - Root Conclusion: The conclusion at the root of the argument tree, which is the only conclusion not also a premiss.

Alias: "Final Conclusion".

In argumentative trees, branch premisses are both premisses and conclusions, albeit of different arguments, so they may be marked with either premiss or conclusion indicators, and sometimes both! Of course, if a statement is marked as both a premiss and conclusion, that is a sure sign that it is a branch premiss.

Here's an example of a passage containing a complex argument:

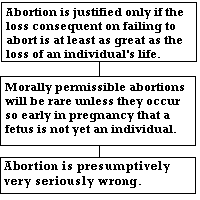

Presumably abortion could be justified in some circumstances, only if the loss consequent on failing to abort would be at least as great [as the loss of an individual's life]. Accordingly, morally permissible abortions will be rare indeed unless, perhaps, they occur so early in pregnancy that a fetus is not yet definitely an individual. Hence,…abortion is presumptively very seriously wrong…. (P. 468)

There are three statements in this passage:

- Presumably abortion could be justified in some circumstances, only if the loss consequent on failing to abort would be at least as great as the loss of an individual's life.

- Morally permissible abortions will be rare indeed unless, perhaps, they occur so early in pregnancy that a fetus is not yet definitely an individual.

- Abortion is presumptively very seriously wrong.

There are two conclusion indicators in this passage: "accordingly" and "hence", showing that there are at least two arguments, and that both the second and last statement are conclusions. The first statement is unmarked and is, presumably, a premiss supporting the second statement. What is the premiss for the final statement? The only possible premiss is the second statement, so that there are two arguments linked by the second statement, which is a conclusion of the first argument and the premiss of the second.

This is an example of the simplest and most common type of complex argument in which two single-premissed arguments are connected in a simple chain. In this case, statement 1 is the leaf premiss, statement 2 is the branch premiss, and statement 3 is the root conclusion.

When confronted with complex arguments, it is often helpful to construct a tree diagram―also known as an argument "map"―like the one for the example argument, in order to display the logical relationships between statements and the ways in which arguments are connected. The more complex an argumentative passage is, the more helpful such a diagram is likely to be in understanding what is being argued, and on what basis. As I mentioned in the previous lesson, an argument must be understood before it is evaluated, or the evaluation will almost surely be wrong. In the next lesson, you'll start evaluating arguments.

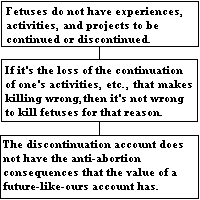

Exercise: Analyze the following complex argument. Determine its leaf premisses, branch premisses, and root conclusion. Draw a tree diagram showing its logical structure.

…[I]f it is the continuation of one's activities, experiences, and projects, the loss of which makes killing wrong, then it is not wrong to kill fetuses for that reason, for fetuses do not have experiences, activities, and projects to be continued or discontinued. Accordingly, the discontinuation account does not have the anti-abortion consequences that the value of a future-like-ours account has.

Source: Don Marquis, "Why Abortion is Immoral", in Robert J. Fogelin & Walter Sinnott-Armstrong's Understanding Arguments (Fifth Edition).

Previous Lessons:

- Introduction

- Statements

- Arguments

- Conclusion Indicators

- Arguments and Explanations

- Premiss Indicators

- Argument Analysis

Next Lesson: Truth-Values and Validity

August 13th, 2007 (Permalink)

The Media and the Median

According to The New York Times:

One survey, recently reported by the federal government, concluded that men had a median of seven female sex partners. Women had a median of four male sex partners. … But there is just one problem, mathematicians say. It is logically impossible for heterosexual men to have more partners on average than heterosexual women. Those survey results cannot be correct.

Actually, there's another problem here: the reported medians are not logically impossible. If you don't remember what "median" means, see the Resource below. Suppose that there are exactly 11 men and 11 women and that the number of their lifetime sex partners are1:

Men: 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7; Total: 42; Median: 7

Women: 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 4, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7; Total: 42; Median: 4

This may not be a likely distribution of sex partners, but it certainly isn't logically impossible. I've written before about how the notion of "average" is confusing because it's ambiguous between two common measures of typicality―mean and median―and a third, less common one―mode. In this case, it appears that median and mean are being confused. It's not logically impossible for the median to be as reported, but it would be impossible for those numbers to be means. So, when the article ambiguously states that "it is logically impossible for heterosexual men to have more partners on average than heterosexual women", by "on average" it must be referring to the mean, not the median.

The article goes on to quote a proof that the numbers of sex partners for men and women must be the same:

By way of dramatization, we change the context slightly and will prove what will be called the High School Prom Theorem. We suppose that on the day after the prom, each girl is asked to give the number of boys she danced with. These numbers are then added up giving a number G. The same information is then obtained from the boys, giving a number B. Theorem: G=B Proof: Both G and B are equal to C, the number of couples who danced together at the prom. Q.E.D.

However, by itself this only proves that the total numbers of male and female partners has to be equal; it says nothing about the "average". As in the example, the totals can be the same but the medians different. However, given the fact that the total numbers of men and women are nearly the same, we can see that the means will also have to be the same. This is because the mean is equal to the total number of partners divided by the total number of men or women. The proof only shows that the numerators are the same; we need the additional fact that the denominators are equal to conclude that the means will be identical.

It's discouraging that an article this innumerate would be published in the Times, and I suppose that the mathematician quoted was not the source of the confusion, but that it must have been introduced in the writing or editing. As it is, there's no evidence in the article of anything impossible in the statistics cited. A British survey is quoted, but the article doesn't indicate whether the numbers are medians, means, or what―which is a problem in itself!

Moreover, the article presents itself as busting the "myth" that heterosexual men are more promiscuous than heterosexual women. Surely, the "myth" is that the typical man has more sex partners than the typical woman. In order for this to be true, there must be some atypically promiscuous women2. Whether the "myth" is true or not, I don't know―damn it, Jim, I'm a logician, not a sociologist! ―but I do know that it is an empirical question and not a logical or mathematical one.

Source: Gina Kolata, "The Myth, the Math, the Sex", The New York Times, 8/12/2007

Resource: "Average" Ambiguity, 11/4/2002

Via: Tom Maguire, "They Can't Mean That! (JOM Goes To The Prom)", Just One Minute, 8/12/2007

Corrections (3/21/2018): There are two corrections to the entry, above:

- I just realized that the example given above to show that the two medians are possible is in error: it shows that only six of the men had any sexual partners at all and that five were celibate. However, it also shows that five of the women had seven sex partners, which is impossible if only six of the men were sexually active. Nonetheless, that the medians are consistent can be shown by the following, simpler example:

Men: 0, 0, 0, 7, 7, 7, 7; Total: 28; Median: 7

Women: 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4; Total: 28; Median: 4

Four of the men had sex with all seven of the women, whereas each of the women had sex with all four of those men. Again, this is not a realistic example, but it shows that there is nothing inconsistent about these medians. Thus, the original point stands: it is logically possible that men have a different average number of partners than women do, so long as the average is the median.

- The opposite is true: some men must have a greater number of partners than others, while women's distribution of partners must be less skewed in order for the male median to be greater than the female one. You can see this effect in the example in the first correction, above. In other words, there has to be less promiscuity, as well as less celibacy, among the women than the men to get this result.

Update (8/14/2007): Mathematician Jordan Ellenberg's latest Do the Math column deals with this issue. As a result, I expect that the Times will issue a correction soon.

Source: Jordan Ellenberg, "Mean Girls", Do the Math, 8/13/2007

Update (8/24/2007): I have yet to see a correction from the Times, which disappoints me further. The Times issues corrections of many trivial errors, whereas almost the whole of this article was misleading.

Update (9/30/2007): The Times did not issue a "correction", but it did publish a "clarification" shortly after the original article appeared and prior to the previous update. I didn't see it until today because I had been checking the corrections page. Unfortunately, the "clarification" doesn't clear it up for me, it just changes what I'm unclear about.

Here's one thing it did clear up: I wondered what the point of the "High School Prom Theorem" was, because it only proved that the total number of partners for men must equal the total for women. The clarification says that this was all that it was supposed to prove, though the original article suggested that the theorem had something to do with the claims about "averages". As I pointed out above, it does have a bearing on the mean, but not without an additional premiss.

My new confusion is caused by the response at the end of the article from David Gale, the mathematician that Kolata was relying on. In the response, Gale says that his claim of inconsistency was based on the raw data. I hate to disagree with Gale, but I don't see it.

A problem with the raw data is that the number of partners claimed by the subjects is given in ranges, rather than precise numbers: 0-1, 2-6, 7-14, and 15 or higher. As a result, one can't tell exactly what the total numbers of partners are. Gale states that no matter how he estimated the totals, the men's claim was considerably higher than the women's. Nonetheless, as far as I can see, the data are consistent.

Suppose that there were a total of 2,000 persons surveyed, half of whom were men and half women. The following tables show their responses:

| No. of Men | No. of Partners | Total No. of Partners |

|---|---|---|

| 166 | 0 | 0 |

| 338 | 2 | 676 |

| 207 | 7 | 1449 |

| 289 | 15 | 4335 |

| No. of Women | No. of Partners | Total No. of Partners |

|---|---|---|

| 250 | 1 | 250 |

| 251 | 4 | 1004 |

| 192 | 6 | 1152 |

| 154 | 12 | 1848 |

| 59 | 13 | 767 |

| 93 | 15 | 1395 |

| 1 | 44 | 44 |

These hypothetical data show the men and women reporting the same total number of partners, and the medians match those given for the CDC data, namely, 7 for men and 4 for women (the medians do not count any claims of zero partners―which only affects that for the men―as this is how the CDC medians were figured. See footnote 1, p. 10 of the CDC report.)

Since these data are consistent with both the High School Prom Theorem and with the raw data reported by the CDC, I don't understand Gale's claim that the data are inconsistent. I suspect that Gale must be right and so I must be missing something; however, the math involved in this example is not exactly sophisticated, so even a lowly logician should be able to understand it. Perhaps some kind, mathematically-inclined reader out there will be able to explain what Gale was getting at, because I'm stumped.

Sources:

- Fryar, et al., "Drug Use and Sexual Behaviors Reported by Adults: United States, 1999-2002", Centers for Disease Control, 7/28/2007 (PDF)

- Gina Kolata, "The Median, the Math and the Sex", The New York Times, 8/19/2007

August 2nd, 2007 (Permalink)

New Book

The latest issue of the Skeptical Inquirer, now on the newsstands, has a favorable review of Lewis Vaughn's book The Power of Critical Thinking. I haven't read this book yet, so I can't specifically recommend it. However, Vaughn is the co-author of How to Think about Weird Things, which is one of the most entertaining textbooks I've read.

Source: David Clapsaddle, Review of The Power of Critical Thinking, Skeptical Inquirer, July/August 2007, p. 57.

Answer to the Exercise: There are two argument indicators: "for", a premiss indicator, and "accordingly", a conclusion indicator. "For that reason" is not functioning as a conclusion indicator in this context, as can be seen by substituting other conclusion indicators for it.

Leaf Premiss: Fetuses do not have experiences, activities, and projects to be continued or discontinued.

Branch Premiss: If it is the continuation of one's activities, experiences, and projects, the loss of which makes killing wrong, then it is not wrong to kill fetuses for that reason.

Root Conclusion: The discontinuation account does not have the anti-abortion consequences that the value of a future-like-ours account has.