WEBLOG

Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

October 31st, 2007 (Permalink)

A Trick or Treat Logic Puzzle

Four children, including Alice, came to the Addams house on Halloween trick-or-treating. The Addamses gave out four different treats, including a gingerbread man, to the children. Each child was dressed in a different costume, including one made up as a zombie, and received exactly one treat. From the following clues, determine the order in which each child arrived, the costume each wore, and the treat that each was given.

- Carla, who came after the child who was given the gingerbread man, did not receive the caramel apple.

- If Billy did not get the brownie, then the child dressed as a vampire came immediately before David.

- The child made up as a werewolf came later than Carla, who didn't get the cupcake.

- If the child costumed as a ghost didn't come before Billy, then David was costumed as a vampire.

- Billy, who preceded the child who received a brownie, didn't get the cupcake because someone else had already received it.

October 26th, 2007 (Permalink)

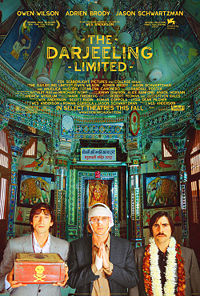

Blurb Watch: The Darjeeling Limited

An ad for the movie The Darjeeling Limited has the following blurb:

"WARM, ENGAGING, AND FUNNY."

ROGER EBERT, CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

Here's what Ebert wrote:

Three brothers in crisis meet in India and in desperation, in "The Darjeeling Limited," a movie that meanders so persuasively it gets us meandering right along. It's the new film by Wes Anderson, who…made "The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou." Of that peculiar film I wrote: "My rational mind informs me that this movie doesn't work. … 'Terminal whimsy,' I called it on the TV show. …" I quote myself so early in this review because I feel about the same way about "The Darjeeling Limited," with the proviso that this is a better film, warmer, more engaging, funnier….

So, Ebert actually wrote that the movie is "warmer, more engaging" and "funnier" than the director's previous film, rather than that it is warm, engaging, and funny absolutely. By changing three adjectives from the comparative degree to the positive, the ad writer changes their meaning, which goes beyond the usual quoting out of context that can be expected in a movie ad blurb into deliberate misquoting. For this reason, I wouldn't call attention to it except for a logical point about comparatives: a comparative adjective does not imply the adjective in the positive degree. That one movie is warmer, more engaging, and funnier than another does not imply that the former movie is warm, engaging, or funny.

Sources:

- Ad for The Darjeeling Limited, The Dallas Morning News, 10/26/2007

- Roger Ebert, "The Darjeeling Limited", 10/5/2007

October 24th, 2007 (Permalink)

Headline

Researchers Track Boobies for Climate Change Data

October 22nd, 2007 (Permalink)

Debate Fallacies, Part 4

In the most recent presidential debate, Rudolph Giuliani said:

I brought down crime more than anyone in this country―maybe in the history of this country―while I was mayor of New York City.

Political office holders like to take credit for the good things that happen while they're in office, while often blaming someone else for the bad ones. Giuliani doesn't simply mention that New York's crime rate fell while he was mayor, but claims that he brought it down. While it's quite possible that Giuliani's policies contributed to the drop in crime, what evidence is there that they actually did so other than the fact that the drop occurred while he was in office?

Annenberg Political Fact Check says that the decline began under the previous mayor―who doesn't necessarily deserve any credit, either, since crime peaked in his term, and the drop may be due at least partly to regression to the mean. Moreover, the decline in crime was not limited to New York City, as Giuliani's policies were, but was a national phenomenon during the same time period. So, it's possible that New York's lower crime rate is due to whatever caused the nationwide drop, rather than to anything Giuliani did.

Giuliani didn't give an actual argument for his claim, so he technically didn't commit the fallacy of cum hoc, ergo propter hoc. Nevertheless, I think that he did set up a logical boobytrap, since some people who heard the debate will conclude that the former mayor was responsible for the decline in crime simply because it happened on his watch.

Sources:

- "Transcript: The Republican Debate on Fox News Channel", The New York Times, 10/21/2007

- Viveca Novak, with Brooks Jackson, Justin Bank, Jess Henig, Emi Kolawole, Joe Miller & Lori Robertson, "Florida Fandango", Annenberg Political Fact Check, 10/22/2007

October 20th, 2007 (Permalink)

Check it Out

Ben Goldacre's latest Bad Science column details an example of the legal form of Argumentum ad Baculum, that is, using a lawsuit or the threat of one to stifle criticism or to keep unfavorable evidence from getting a hearing. Apropos of the recent debate about objectivity and science, he contrasts the treatment of criticism by a pseudoscience with that of genuine science. Openness to criticism is one of the hallmarks of scientific objectivity; using the threat of lawsuits to silence critics is a sign of pseudoscience.

Source: Ben Goldacre, "A corporate conspiracy to silence alternative medicine?", Bad Science, 10/20/2007

October 12th, 2007 (Permalink)

Fact Check it Out

How can you fact check political ads when they have no facts? The Fact Checking folks at Annenberg discuss vague and unspecific political advertisements.

Source: Brooks Jackson & Jessica Henig, "99% Fact-Free", Annenberg Political Fact Check, 10/12/2007

October 9th, 2007 (Permalink)

Q&A

Q: There's a speaker coming to my college, who, if I read the excerpts of his work correctly, argued that math cannot be objective because most mathematicians were white. Regardless of whether I actually read the piece right, the similar argument that science cannot be objective because most scientists are male is one that I've certainly heard before, and decided to try to look it up on your site. I'm curious, it seems like this ought to be a distinct sort of fallacy, but I'm not sure what exactly. It seems to be a combination of ad hominem and conclusion not following from premise. I was wondering whether it has a special sort of name?In a similar vein is the argument that some positions cannot be taken by certain persons because of a lack of experience. The classic example is men cannot hold a position on abortion because men cannot have children, such as you cite in "Poisoning the Well." You note that this is not technically a fallacy, which makes sense to me. It does, however, bring to mind an argument that I once had with a communist. He argued that because the position I took was in line with my self-interest, it was therefore an invalid argument. I'm fairly certain that this is a simple ad hominem attack without a special name, however since I'm emailing you at any rate, I thought I'd ask whether this has a special name as well.―Luke Kundl Pinette

A: I've come across arguments similar to these, and they're all forms of the genetic fallacy, that is, arguments that reject an idea, claim, or argument because of its source. When the arguments are directed at a specific person, they are more specifically ad hominem or poisoning the well, as you indicated, both of which are types of genetic fallacy. Whether it's an ad hominem attack or poisoning the well depends upon when the attack is launched, as poisoning the well is a kind of pre-emptive ad hominem. I don't know of a more specific name than "ad hominem" or "poisoning the well" for these types of genetic fallacy.

The important thing, when confronted by claims such as these, is to keep your eye on the argument and not be distracted by red herrings. Whenever someone tries to change the subject from the argument to the person advancing it, it is probable that some type of genetic fallacy is at work. There are rare occasions when such facts may be relevant, but you can always ask the person raising them: "So what?" The burden of proof is on them to make the connection. How is skin color relevant to a proof? Sufficiently explicit proofs can be checked for correctness by a computer; that's what makes them proofs. If the communist were right, then any time a worker argued for communism the argument would be invalid, since communism is in the worker's self-interest―at least, according to communists! That's absurd, however, since the same argument can be made by a capitalist such as Engels. The validity of an argument does not depend upon who makes it.

Whether the mathematician who proves a theorem is white, black, male, female, human, or even a machine, is irrelevant. There is no such thing as white mathematics or male science, as opposed to non-white mathematics or female science, just as there is no Aryan science as opposed to Jewish science, and for the same reasons. People who oppose racism and sexism should celebrate the objectivity of mathematics and science, not attack it.

Update 10/10/2007: Steven Lopez, an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ohio State University, wrote to take issue with my answer to Luke's question. His comments are long, so I will interpolate my replies. He begins:

I've read your Q and A for October 9, and I found it interesting. I think you've oversimplified things rather badly with respect to objectivity and science, and I thought it would be worthwhile to take the time to comment. The claim was "science is not objective because most scientists are men" and you said it was an instance of the genetic fallacy on the grounds that it involved rejecting "an idea, claim, or argument because of its source." I do not believe that you are correct. Please allow me to explain.

Be my guest.

The problem is that "science" is not merely an "idea, claim, or argument." It is a complex human endeavor involving institutional as well as individual behavior. Moreover, as anyone familiar with the sociology of science―i.e., the empirical study of what scientists actually do―will tell you, actual scientific work involves interests, imagination, and passion in addition to skepticism and method.Consider the following argument, which I believe is valid (though the premises are debatable):

- Scientists study things that interest them.

- The kinds of things that people are interested in vary, in certain respects, by gender.

- Most scientists are male.

Given these premises, the conclusion that scientists will tend to neglect questions that women are interested in but men are not, is, I believe, a valid one. Indeed, I believe that these premises are substantially true and that, therefore, the conclusion is also true.

Let's take an example from the social sciences. It is a true statement that men, in general, are not very interested in the question of why men don't do their fair share of housework. This is a question that men, on the whole, do not like to think very much about. It is not a coincidence that the social scientists who are studying this question―such as my excellent colleague here at Ohio State, the sociologist Liana Sayer―are mainly women. Indeed, an all-male sociology would never study gender in the same way that our field currently does. Interestingly, questions such as this one are still far more marginal to the field of sociology than they really deserve to be given their importance. There is a good deal of recent work demonstrating that markets cannot exist at all without floating on a sea of unpaid female labor. And yet the study of market behavior is very high in prestige for economic sociology, for economists, and so on, while the study of unpaid domestic labor is female and unprestigious.

Do you really want to argue that the same patterns cannot be found in the so-called "hard" sciences? Especially in applied sciences? It took many years of critique by women scientists before medical research trials routinely included women. Heart disease was assumed for decades to be mainly a problem for men, because nobody bothered to see whether it affected women equally as often. Do you really think these lapses would have persisted as long as they did had women been better represented in the scientific disciplines involved? Come now.

You're right, I don't want to argue that. I was defending the objectivity of science. It seems reasonable that men and women may tend to be interested in different things and, therefore, male scientists may tend to study different subjects than female ones do. I don't see what that has to do with objectivity. Unfortunately, "objectivity" is a vague and ambiguous word, but I don't mean to suggest by that term that what individual scientists choose to study isn't affected by all sorts of factors, especially economic ones. What you say seems to be an excellent argument for encouraging more women and non-whites to become scientists.

Relatedly, it is interesting to consider what happens when men (or any other dominant group) are permitted to dominate the study of something about which they have material interests relative to some subordinate group. In these kinds of cases, these dominant group members are quite likely to produce bad science that justifies their privileged position. The history of science is replete with this sort of thing. For decades, an all-male social science insisted that a gender division of labor in which women did housework and raised children, and men did their thing outside the home, was natural and right. It took women to come along and break up this orthodoxy. Going back a bit further, male scientists compared the size of male and female skulls to argue that men were naturally more intelligent, women naturally less intelligent. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, racist and eugenic scientists in biology produced large bodies of work demonstrating the natural inferiority of Jews, Negroes, etc. Indeed, you say that there is no such thing as an Aryan science but there certainly was such a thing, and it did a good deal of harm in the world. Do you want to argue that bad science has nothing to do with who was involved and who was kept out? That a biology in which blacks and Jews were well-represented would have been equally likely to produce racist science?

Again, that's not what I had in mind by the objectivity of science. In particular, I didn't mean to include pseudosciences as "science". Not everything that someone somewhere has called "science" is, thereby, in fact science. This is what I meant in saying that there is no such thing as "Aryan science" or "Jewish science". Of course, the Nazis talked about such things without putting them in scare quotes, but that doesn't make them science. Some people talk about "creation science", but that's not science, either. Science is just plain science, whoever does it, "Aryan" or Jewish.

I am not arguing that the ideas of racist or sexist science were wrong simply because they were produced by members of the dominant group. They were wrong because they can be shown empirically to have been wrong, not simply because they were self-serving. Some self-serving ideas may be correct after all, and I obviously would agree that the statement "your argument is wrong because you are a man" is invalid because ad hominem. But the reason white and male scientists liked certain racist and sexist ideas is in large part because they were self-serving―and it is not an ad hominem attack to claim that keeping members of socially-subordinate groups out of science is quite likely to affect both the subject matter of scientific inquiry and the quality of scientific ideas in at least several scientific fields.

You seem to be attacking a straw man, as I certainly don't think that it's a good thing to either produce false theories or to keep people out of science; quite the opposite.

The additional observation is that your claim that "People who oppose racism and sexism should celebrate the objectivity of mathematics and science, not attack it" appears to be completely unfounded in any argumentation whatsoever. Nothing you say leading up to that conclusion is in any way logically relevant to it! It's a complete non sequitur.

Perhaps I should spell out what I was trying to get at by focusing on the science that I know best, namely, logic. What sex or color you are is irrelevant to whether you have successfully proven a theorem in logic. No logician ever asks the sex or race of the person who proved something. In fact, it's not uncommon that I have no idea who proved a theorem. It just doesn't matter! That's why I mentioned the fact that proofs can be checked by computers. This is the sort of thing I mean by the "objectivity" of logic. Logic is completely egalitarian, as the sex or color of a logician is irrelevant, which is what I think deserves celebration rather than hostility. This is true of science in general, though not all sciences are as objective as logic, unfortunately. However, anything deserving to be called "science" is objective to some degree.

Should black people celebrate the objectivity of the "culture of poverty" theory? Should women celebrate the objectivity of sociobiologists who do shoddy evolutionary thought experiments to "prove" that women are from Venus while men are from Mars? In light of the many sorry episodes in the history of science in which racism and sexism underlaid (and indeed, in the social and biological sciences, continue to underlay) respected scientific theories, why is it unreasonable for people who oppose racism and sexism to continue to be on the lookout for it in science? While it is true that attacking examples of it is best done by proving it wrong (rather than simply calling it racist or sexist, which doesn't by itself prove it wrong), there's no reason to assume at the outset that science (and scientists) are automatically exempt from these maladies, that scientists can't be racist and/or sexist, that their racism and/or sexism can't creep into their work.

Again, you're tilting at a straw man. If you read the Fallacy Files, you'll see that I certainly don't assume that scientists are incapable of error. In fact, one of the purposes of the Files is to document such errors when they are logical in nature. Scientists are people too, and people are subject to various cognitive biases that lead to errors, including logical fallacies.

I'm not sure, but I don't think that we really disagree all that much, except about the meaning of the word "objective". I have no idea what you mean by it, since I would never call a false theory "objective". To quote from The Princess Bride: "You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means."

Update 10/11/2007: Steven Lopez responds to my reply:

You have now claimed:

- Science is objective.

- False theories are not objective.

The conclusion that false theories are not science is inescapable. But if false theories are not science, then science consists only of the collection of things currently believed to be true―an absurd notion.

The argument is invalid because it equivocates on "objective". The sense in which a false theory is not objective is a different sense of "objectivity" than the sense in which science is objective. A false theory is not objective because it fails to correspond with reality. In contrast, science is objective because of the methods that it uses to test its theories, such as proofs. The first is a metaphysical notion of objectivity, whereas the second is epistemological.

I only mentioned false theories because you referred to some theories that you said were "wrong" as objective, which confused me. I wouldn't think that a "wrong" theory would be "objective" in any sense of the word.

Consulting a variety of dictionaries reveals that one of the most common definitions of "objective" is some version of the following: "uninfluenced by personal emotions or prejudices." So the claim that "science cannot be objective because most scientists are men" could quite reasonably be read "science cannot be uninfluenced by personal emotions or prejudices because most scientists are men." In other words, if men dominate science, male prejudices will influence science. The claim doesn't hinge on the idea of male prejudices influencing the nature of logic or the validity of proofs! It only hinges on the idea that male prejudices will "influence science." Science is more than the logic of proofs. The choice of questions―for example―is part of the scientific process. If the choice of questions in science is influenced, then science is influenced. Your narrow focus on logic as the defining feature of science is not justifiable in this context. I do not think you have shown that the original claim was a logically fallacious, ad hominem attack on an idea, claim, or argument.

I think that this argument overshoots the mark. Human beings are influenced by emotions and prejudices, and science is the product of human beings. The questions that scientists ask and the research that they pursue are no doubt the result of their interests as human beings. When people say that science is objective, I doubt that they mean to deny that it is the product of human beings, and I certainly don't deny that. If all you're claiming is that the direction of research is not "objective", because it's based upon human interests, then we can agree on that. I never meant to claim that that part of science is objective, because I don't know what that would mean.

I focused on logic for two reasons: it's the science that I know best, and proofs are the clearest examples of objectivity in science. I don't know how to define "objectivity" except ostensively, so I'm pointing to examples to try to explain what I mean. It's only that sense of "objectivity" that I'm claiming for science.

It sounds as though you may accept that logical proofs are objective in that sense. If so, then you may be able to see how logic is able to be objective despite the fallibility of human logicians. Since logic is a science, then at least that part of science is objective. And, since mathematics as a whole is based upon logic, math itself is objective, despite the fact that most past mathematicians were fallible white men.

Update 10/16/2007: Steven Lopez replies to my response:

I really wonder about that. What if the rules of logical reasoning reflect our own cognitive structures rather than anything about the way the world works? Logic tells us that a proposition can't be simultaneously true and false, but at the scale of the very small, observations tell us that things get very weird and logic breaks down. Things can be in two places at once, and so on. Along these lines, mathematics seems to be very useful in describing the world out there, but we don't know for sure that this has anything to do with the nature of the universe. Both logic and mathematics are symbolic languages, very much like music and English are symbolic languages. We use language―whether English or mathematics―to describe the world. To say that math is "objective" in your sense says only that language rules are objective in precisely the same sense that "i before e except after c is true for everyone who speaks English" is objective. Is this not so?

That sounds about right, in the epistemological sense of "objective" which is relevant to the original question, though this is not to say that science in general is not "objective" in the metaphysical sense, as well. However, that kind of objectivity is not needed to answer the original question. The reason it is fallacious to dismiss mathematics as not "objective" because it is the work of white people is that anyone, no matter their color, can check the work of mathematicians for themselves. Mathematical proofs either succeed or fail on their own merits, and not because of the skin color of those who produce the proofs.

Perhaps if more non-whites had been mathematicians, the direction of mathematical research would have been different, though I doubt it. There are an infinite number of possible theorems in logic and math, but we can only prove a finite number of them, and those that we choose to prove depend upon what we're interested in. However, it's not the direction of scientific research that is objective, but its results.

By the way, it's not logically impossible for something to be in two places at once, though this violates our common sense notion of how things behave. So, you might say that common sense breaks down at the quantum level―which is not surprising, given that it's based upon our experience with macroscopic objects―but not logic.

Update 10/17/2007: Steven Lopez issues a clarification:

In your latest blog entry, you mention "the original question" and then refer to the question of whether it was fallacious to say that math isn't objective because most mathematicians are white, as if we've been arguing about that the whole time. I never said anything about that at all! I directed all my comments to the second question raised by the original question-writer: namely, whether it is fallacious to say that science isn't objective because most scientists are men. I'd appreciate it if you'd clarify this on your blog, because now the waters are pretty muddy and someone might wrongly conclude that I agree with the first claim.

Update 10/18/2007: Here's a clarification of my own. Steven points out an apparent contradiction:

First you say that the conclusion, false theories aren't science, doesn't follow from your two statements because you're using the term "objective" in two different senses. Fine. But then you say that false theories can't be objective in any sense of the word. But any sense of the word must include the sense you are using when you say that science is objective. In that case the conclusion would follow.

There is a subtle point here: When I said "I wouldn't think that a 'wrong' theory would be 'objective' in any sense of the word", I didn't mean that such a theory would, therefore, be "not objective" or "non-objective" in every sense of the word. Specifically, I don't think that the epistemic sense of the word applies to theories at all, so it doesn't apply to false theories, a fortiori. This is because epistemic objectivity is a property of scientific method, rather than the results of science. When I said that science is objective, I meant that scientific method is epistemically objective.

In other words, to say of false theory T either "T is epistemically objective" or "T is not epistemically objective" is a category mistake. For example, it's not true to say that the number seven is red, but that doesn't mean that the number seven is not red. Numbers are not the sort of thing to have colors, and the sentences "seven is red" and "seven is not red" are not, therefore, propositions. So, the argument lacks a second premiss because "false theories are not (epistemically) objective" is not a proposition.

I'm sorry for not having explained this better, and I'm not surprised that it's confusing. I've been looking for a good source that might address scientific objectivity better than I've been able to, but haven't found much to recommend. The best that I've come up with are two books by the philosopher and logician Susan Haack. I haven't yet read her book Defending Science, so I'm recommending it on the strength of her past work, in particular two essays from her collection Manifesto of a Passionate Moderate that I have read. Unfortunately, the essays are fairly philosophically sophisticated; hopefully, the more recent book is a better introduction to the subject.

Resources: Susan Haack,

- Defending Science―Within Reason: Between Scientism and Cynicism (2003)

- "Multiculturalism and Objectivity" & "Puzzling Out Science", in Manifesto of a Passionate Moderate: Unfashionable Essays (1998), Chapters 8 & 5, respectively.

Debate Update (10/21/2007): Here's Steven:

So you're using two senses of the word "objective." Metaphysical objectivity is about correspondence to reality and epistemological objectivity is methodological. Metaphysical objectivity, but not epistemological objectivity, applies to theories. Theories may or may not correspond to reality in your view (and theories which do not are not metaphysically objective), but the quality of epistemological objectivity doesn't apply. Epistemological objectivity thus seems to come into play in theory testing only.Your argument has been that logic and method in scientific theory-testing are epistemically objective, in the sense that the results of a statistical analysis will be the same whether the proportion of women in science is 0% or 100%. We don't have a dispute here.

That's good!

But the original question was whether it was fallacious to say that "science is not objective because most scientists are men." Your answer appears to be yes―it's fallacious because logic and method in theory-testing are epistemically objective.

Thanks! You summarized that more clearly and concisely than I stated it originally, though it does go to show that I was less obscure than I feared.

But of course, logic and method in theory-testing comprise just one part of the scientific process, and epistemic objectivity is just one of the two types that you define. It is not clear to me why (a) you regard only epistemological objectivity, but not metaphysical objectivity, as relevant to the original question, and (b) why you apparently consider it reasonable to exclude from discussion parts of the scientific process to which epistemological objectivity do not apply, but which may be relevant to the metaphysical objectivity of science―such as choice of questions and generation of theories.

I think that the argument commits a fallacy of relevance―what I call a "red herring"―because the historical fact that most scientists have been men seems to have no connection to the conclusion in any sense of "objectivity". Since the argument rejects the objectivity of science on the basis of its origin, that makes it an instance of the genetic fallacy.

I concentrated on epistemic objectivity only because I'm a logician and philosopher of science and most interested in scientific method. Since metaphysical objectivity has to do with correspondence with reality, I don't see how maleness is relevant to a lack of it, either. Even if there were some reason to believe that men are more likely to come up with false theories than women, there are established methods for testing theories which don't involve inquiring into the sex of those who propose them. Theories, like arguments, have to stand or fall on their own, and not on the basis of who proposes or opposes them.

By "choice of questions", I assume that you're referring to the decisions made by scientists as to what type of research to pursue. This is an area in which neither concept of objectivity seems to apply, in the sense that it's a category error to call it "objective" or "non-objective". Even if it were correct to say that the direction of research is subjective because it's determined by our interests, that doesn't seem to affect whether the methods of science are epistemically objective, or its results metaphysically objective. I'll settle for those two types of objectivity.

As for the generation of theories, again, this is an area where objectivity is not really an issue. We have to use our imaginations to create new theories, and most theories turn out to be false. Objectivity only enters at the testing stage and, if we're lucky, when we've eliminated the false theories and, again, I'll settle for that.

October 6th, 2007 (Permalink)

LSAT Logic Puzzle

A few readers have written to ask for my advice on how to study for the Law School Admission Test. Now, I've never taken the LSAT, so I don't know about it from personal experience. However, the LSAT apparently tests skills that lawyers need, including reading comprehension and logical reasoning. Judging from sample tests that I've seen, it uses logic puzzles to measure reasoning ability. If you're planning to take the test, a general recommendation is that you practice working such puzzles as much as you can. Here's a sample:

Bird-watchers explore a forest to see which of the following six kinds of birds―grosbeak, harrier, jay, martin, shrike, wren―it contains. The findings are consistent with the following conditions:

- If harriers are in the forest, then grosbeaks are not.

- If jays, martins, or both are in the forest, then so are harriers.

- If wrens are in the forest, then so are grosbeaks.

- If jays are not in the forest, then shrikes are.

If both martins and harriers are in the forest, then which one of the following must be true?

(A) Shrikes are the only other birds in the forest.

(B) Jays are the only other birds in the forest.

(C) The forest contains neither jays nor shrikes.

(D) There are at least two other kinds of birds in the forest.

(E) There are at most two other kinds of birds in the forest.

Source: Powerscore, LSAT Logic Games Bible, p. 133.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to René Erard, Talula Macioce, and Irry Toh.

October 2nd, 2007 (Permalink)

Lessons in Logic 9: Truth-Values and Validity

In Lesson 2, "statements" were defined as sentences with a truth-value. In Lesson 3, "arguments" were defined as sets of statements in which one is alleged to follow from the rest. Since an argument is not itself a statement but a set of statements, it is incorrect―though a common type of illogicality―to call an argument "true" or "false". Truth-values are used to evaluate statements, not arguments. In this lesson, you'll learn some terminology for evaluating arguments.

An important question to ask about evaluation is: What standard or goal is to be used? Statements can be evaluated according to many different standards: they are easy or hard to understand, beautifully expressed or ugly, to the point or irrelevant, etc. Truth-values are used to evaluate statements when the standard is correspondence to reality. An important goal that we often have when making statements is to convey information about the world, and truth-values are a measure of whether statements succeed or fail. Of course, there are other goals in making statements; for instance, fiction usually consists of falsehoods, but correspondence with reality is not the proper standard for evaluating fiction.

What is the standard for evaluating arguments? As with statements, there are many standards for evaluating arguments, such as clarity, interest, elegance, relevance, etc. However, an important goal of argumentation is to show a connection between the truth-values of some statements―the premisses―and that of another―the conclusion.

There are two types of logical connection between premisses and conclusion:

- Necessity: The truth of the premisses necessitates the truth of the conclusion. This is the strongest possible connection between statements, and when arguments are judged according to this standard they are called "deductive".

- Probability: The truth of the premisses makes the conclusion more likely to be true than false. When arguments are judged by this standard they are called "inductive".

The remainder of this lesson will concern deductive arguments. Here is an example:

Every President of the United States (POTUS) is at least 35 years old.

George W. Bush is POTUS.

Therefore, George W. Bush must be at least 35 years old.

Q: How can you tell that this is a deductive argument?

A: A tip-off is the occurrence of the word "must" in the conclusion. "Must", and synonyms such as "necessarily", often function as "deduction indicators". Just as "therefore" signals that "GWB is at least 35 years old" is the conclusion of the argument, "must" indicates that the relation between the premisses and conclusion is deductive.

Q: Does the truth of the premisses of the argument necessitate the truth of its conclusion?

A: Yes, if the premisses are true then the conclusion must be true. Such an argument is called "valid".

Definition: A valid argument is one the truth of whose premisses necessitates the truth of its conclusion.

Here's another example:

Every POTUS is at least 100 years old.

Hillary Clinton is POTUS.

Therefore, Hillary Clinton has to be at least 100 years old.

Q: Is this a deductive argument?

A: Yes. "Has to be" in the conclusion is a deduction indicator.

Q: Is the example valid?

A: Yes. Despite the fact that all of its statements are false, the truth of the premisses necessitates the truth of the conclusion. If it were true that all POTUSes are at least 100 years old and Hillary Clinton is POTUS, then it would have to be true that Hillary Clinton is at least 100 years old.

So, valid arguments may have one or more false premisses and, if so, even a false conclusion. The only combination of truth-values that validity rules out is all true premisses and a false conclusion. So, any argument with true premisses and a false conclusion must be invalid. Here's an example:

Every POTUS is at least 35 years old.

Hillary Clinton is at least 35 years old.

Therefore, Hillary Clinton must be POTUS.

This is an invalid deductive argument, since its premisses are true and its conclusion false, so the truth of its premisses does not necessitate the truth of its conclusion.

Validity is the strongest possible logical connection between the premisses of an argument and its conclusion. You can think of validity as a truth pump: put in true premisses and out comes a true conclusion.

Exercises: Are the following arguments valid or invalid?

- Every POTUS is at least 35 years old.

Jenna Bush is younger than 35.

Therefore, Jenna Bush cannot be POTUS. - Every POTUS is at least 35 years old.

Jenna Bush is not POTUS.

Therefore, Jenna Bush must be younger than 35. - Every POTUS is at least 60 years old.

George W. Bush is POTUS.

Therefore, George W. Bush has to be at least 60 years old. - Every POTUS is at least 35 years old.

A cloudless daylight sky looks blue.

Therefore, the earth must be round. - Every dog is an animal.

Every cat is an animal.

Therefore, every dog is a cat. - Every snark is a boojum.

The jabberwocky is a snark.

Therefore, the jabberwocky must be a boojum.

Previous Lessons:

- Introduction

- Statements

- Arguments

- Conclusion Indicators

- Arguments and Explanations

- Premiss Indicators

- Argument Analysis

- Complex Arguments

Next Lesson: Soundness and Cogency

- Valid.

- Invalid: Even though all its statements are true, the truth of the premisses does not necessitate the truth of the conclusion.

- Valid: Even though the first premiss is false, if it were true then the conclusion would have to be true, as well.

- Invalid: Even though all the statements are true, there is no logical connection between them.

- Invalid: The premisses are true and the conclusion is false.

- Valid: The fact that you don't know whether the statements are true or false does not matter; if the premisses were true then the conclusion would have to be true.

Solution to the LSAT Logic Puzzle: E.

You won't be seeing this exact puzzle on the LSAT, of course, but you may well see a similar one. The structure of such a puzzle involves a list of items―in this case, six types of bird―and a list of rules which give you information about the items. One of the best ways to work this type of puzzle, especially when taking a test and your time is limited, is to make a list of the items. Helpfully, the names of the items in the puzzle usually start with different letters of the alphabet, and they will often be listed in alphabetical order, so you can abbreviate them with a single letter. For this puzzle, you could write out the list in the margin of the test booklet or on a piece of scratch paper, so:

G H J M S W

Here, your task is to figure out which types of bird are in the forest, but in other puzzles you'll be trying to figure out something similar, such as, say, what color of jelly bean is in a jar. To indicate that a type of bird is in the forest, you can underline its letter in the list; and, to indicate that no birds of that type are in the forest, cross out its letter.

It's a good idea with such puzzles to, first, read the whole puzzle over quickly, but to start working from the question. It's vital to be clear about what it is you're being asked. In this case, the question at the end is hypothetical: "If both martins and harriers are in the forest, then which one of the following must be true?" So, you're being asked to hypothesize that there are martins and harriers in the forest, and then to see what follows from that hypothesis. The hypothesis gives you your first information; underline martins and harriers in your list, which should now look like this:

G H J M S W

Now, the rest of the information in the puzzle is contained in the four rules, each of which is a conditional statement. Proceed down the list of rules and add information to your letter list:

- Given that you know that harriers are in the forest, this rule tells you that grosbeaks are not, so cross out G in your list:

GH J M S W - Since you already know that harriers are in the forest, this rule tells you nothing new.

- Since you know that grosbeaks are not in the forest, then this rule means that wrens are also not in the forest. Cross out wrens:

GH J M SW - Checking your list, you see that you don't know whether jays or shrikes are in the forest, so this rule tells you nothing new.

Go back over the rules with all the information you now have and see whether there is anything new that you can add. There isn't, so you're done. Now, go down the list of possible answers:

(A) Incorrect. Shrikes and jays are both neither underlined nor crossed out, so you don't know whether or not they're in the forest.

(B) Incorrect. Ditto.

(C) Incorrect. Ditto.

(D) Incorrect. Again, you don't know whether there are any other kinds of bird in the forest, so at this point you know that (E) must be correct, since it's the only remaining choice.

(E) Correct. Your list shows that jays and shrikes are the only other types of bird that might be in the forest, since grosbeaks and wrens have been eliminated.

Here are some general suggestions for working this kind of puzzle: Keep in mind that conditional statements are rules that have a directionality to them; learn the difference between conditional and biconditional statements, that is, the difference between "if…then" and "if and only if".

Learn the validating types of argument with conditionals: modus ponens and modus tollens. Both of these types of reasoning were used in solving the puzzle, and you should be able to identify where. Learning about logical fallacies will also come in handy here, specifically, the formal fallacies of affirming the consequent and denying the antecedent.

If you have the time and energy to study books before the LSAT, the ones most likely to help you with this type of logic puzzle are those on propositional logic. Most introductions to logic will have one or more chapters covering it, and some books are specifically devoted to it. In addition, Irving Copi's introduction used to have a chapter on solving logic puzzles, which would be especially helpful. I don't know whether the current edition still does, but an earlier edition would be just as good―and cheaper! The eighth edition has a section on logic puzzles and in the tenth edition it is expanded to an entire chapter. There are also books and magazines devoted to logic puzzles, and many will have instructions on how to solve them. However, the most important factor is practice!

Solution to the Trick or Treat Logic Puzzle (11/15/2007):

- Alice, dressed as a ghost, received a cupcake.

- Billy, in a zombie costume, got the gingerbread man.

- Carla, done up as a vampire, was given a brownie.

- David, costumed as a werewolf, got a caramel apple.

Congratulations to John Congdon, who received the new and improved Fallacy Files spurious prize for sending in the best solution to the puzzle!