Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

WEBLOG

November 28th, 2024 (Permalink)

Thanksgiving Chez Blanc

It's Thanksgiving again at the Blanc house* and everyone is there, except Ferdinand, who couldn't make it this year. As usual, the family members have gathered around the big round table in the dining room for the traditional feast. From the following clues, determine the age of each family member and their seating position around the table, starting with Abner and proceeding clockwise.

- Claudia is ten years older than the family member who sits immediately to her left.

- The family member on her immediate right is eight years younger than Edwina.

- Claudia, who is 54, is Beatrix' mother.

- Douglas, who is nineteen, is the only family member younger than Edwina.

- Beatrix is seventeen years older than the person sitting next to her on the left.

It will probably help to draw a circular diagram of the table and the five positions around it.

The seating order, going clockwise around the table, and ages are: Abner, 44; Beatrix, 36; Douglas, 19; Edwina, 27; and Claudia, 54.

Explanation: From clue 4, Douglas is the only member of the family younger than Edwina, so he is sitting to her immediate right, by clue 2. By clue 4, Douglas is nineteen, therefore Edwina is 27, by clue 2, again. From clue 1, Claudia is only ten years older than the person sitting to her immediate left, so this cannot be Beatrix, who is Claudia's daughter, by clue 3. Also, whoever is sitting to Claudia's left must be 44 years old, so it cannot be Douglas, who is nineteen, and it isn't Edwina, who is on Douglas' left. So, the person on Claudia's left is Abner, who is therefore 44 years old. Finally, according to clue 5, Beatrix is seventeen years older than the person on her immediate left: this cannot be either Edwina, who is to the immediate left of Douglas, or Abner, who is to the left of Claudia. So, it's either Douglas or Claudia―but it can't be Claudia, who is Beatrix' mother, which makes it Douglas. Douglas is nineteen, which makes Beatrix 36. Putting these facts together, the seating arrangement is: Abner, Beatrix, Douglas, Edwina, and Claudia.

*For last year's Thanksgiving at the Blanc's, see: A Puzzle to be Thankful For, 11/23/2023.

November 23rd, 2024 (Permalink)

Charts & Graphs1: Half a Graph

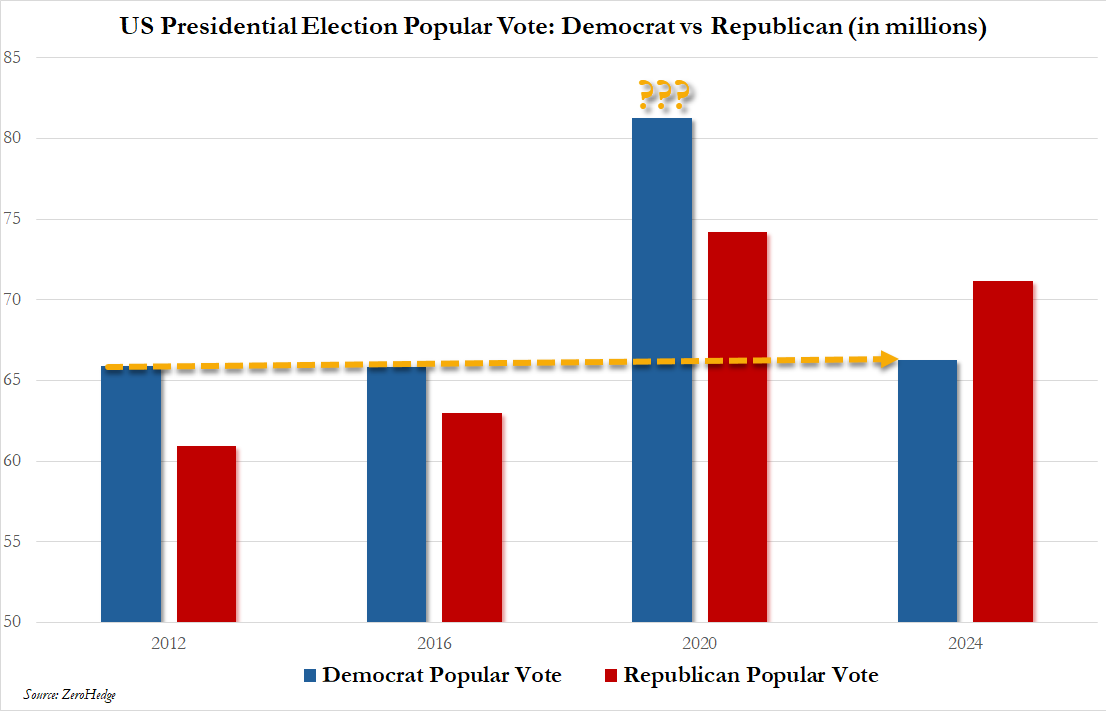

The bar chart shown above, which has been widely shared on anti-social media2, has two things wrong with it, one of which has to do with the data and the other with how the data is displayed. But before we get into the graph's deficiencies, let's figure out what it's trying to tell us.

The chart shows what purports to be the popular vote for the two major-party candidates in the last four presidential elections. Following the contemporary color convention, the blue bars represent the Democratic vote and the red the Republican. In addition to the basic data in the chart represented by the height of the bars, there are two indications of what the graph's creator wants us to notice: the long arrow and the question marks. The arrow draws our attention to the popular vote for the Democratic candidates in the 2012, 2016, and this year's elections, which appear to be approximately the same3. In contrast, the three question marks single out the blue bar for the 2020 election, suggesting that there's something questionable about the Democratic vote for that year, presumably because it's so much greater than the surrounding years.

Now that we understand the message of the chart, let's turn to its deficiencies.

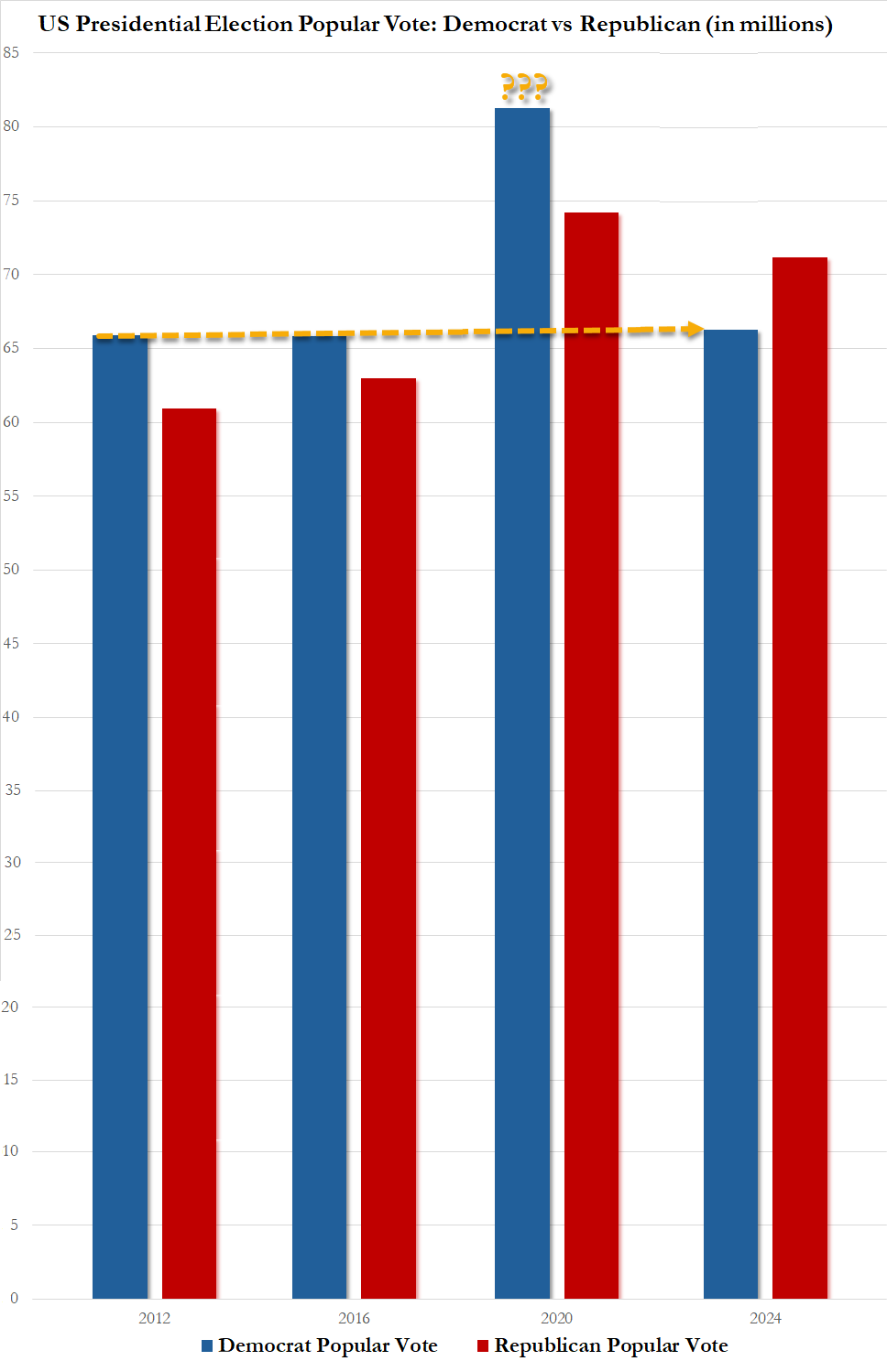

The graph is an example of what I call, following Darrell Huff's lead4, a "gee-whiz bar chart"5. If you look closely at the faint numbers in the scale on the left of the graph, you'll see that the baseline is 50 million votes rather than zero, which has the effect of exaggerating the difference in heights between the three short blue bars and the tall one. To the eye the 2020 bar appears to be almost twice as tall as the three others, yet if you read the vote counts off the scale you'll see that the vote in each of those years was about 66 million, whereas the vote in 2020 is shown as about 81 million. So, instead of being twice as big, the 2020 vote was less that a quarter greater. For comparison purposes, to the right is what the graph would look like with the baseline starting at zero.

The purpose of a bar chart is to make it easy to compare quantities by comparing the heights of the bars, since it's easier to compare lengths visually than to compare numbers mentally. Truncating a bar chart defeats this purpose. In addition, if it is necessary to truncate a graph, it's good practice to indicate visually that the bottom has been cut off, making it less likely to mislead the viewer. That was not done with this chart so that it's only by looking closely at the small numbers in the scale that the reader can realize that it's truncated.

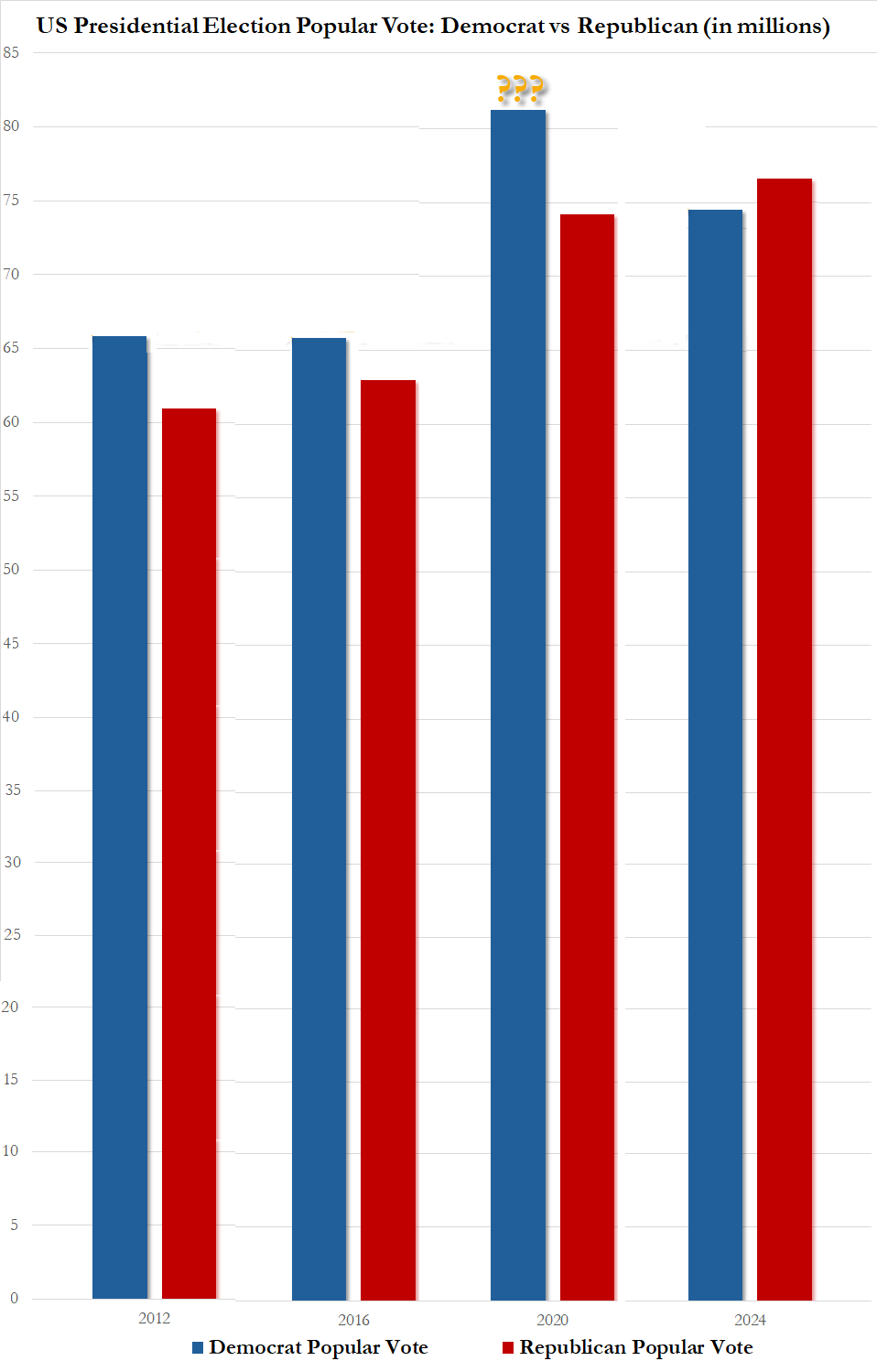

Now, let's turn to the problem with the data. The chart seems to have been created the day after the election, so the popular vote for this year was incomplete. If we update the graph with more recent data6―see the revised graph to the right―the arrow from the original would no longer point to the top of the last blue bar, so I've removed it. While it's clear from the revised chart that the popular vote for 2020 is an outlier, its difference from that of two years prior and this year is substantially less than the original chart suggested. Given that 2020 was the first year of the pandemic, and voting by mail was greatly increased, is it really so surprising that the vote for the winner that year was about four million greater than the vote for this year's winner?

Notes:

- Some previous "Charts & Graphs" entries:

- Charts and Graphs, 6/4/2012

- A "Gee-Whiz" Graph, 8/14/2012

- A Charts & Graphs Prize Contest, 5/8/2014

- This appears to be the initial source of the chart: Zero Hedge, "Sorry to beat a dead horse, but can we go back to what happened here?", X, 11/6/2024.

- For the 2012 and 2016 results, see: "United States Presidential Election Results", Britannica, 11/6/2024.

- Darrell Huff, How to Lie with Statistics (1954), Chapter 5: "The Gee-Whiz Graph".

- See: The Gee-Whiz Bar Graph, 4/4/2013.

- "US presidential election results", Reuters, 11/23/2024

November 19th, 2024 (Permalink)

The End of the "Trump Effect"1

I have good news and I have bad news for the pollsters. First, some good news.

The public opinion polls in this election were about as accurate as could be expected. Despite some claims to the contrary, this election was close and not a "landslide" for president-elect Donald Trump2. The most recent results show Trump's margin of victory over Vice President Kamala Harris in the popular vote as a little over 2.5 million votes, or 1.6 percentage points3, which is about half of the usual margin of error for national polls.

Now, the bad news: even though the polls were reasonably accurate this year, that doesn't mean that they were of any use in predicting who would win. The best bet of doing that is through averaging the results of all the polls taken within a week or two of the election. Here's a summary of such averages from a recent article:

The national polling averages…all showed Harris with an advantage: She led by 1.2 percent per FiveThirtyEight, one percent per Nate Silver, 2 percent according to the Washington Post (which rounds numbers), and one percent according to the New York Times (which also rounds numbers). RealClearPolitics…showed Harris leading by 0.1 percent.4

Averaging the averages gives very slightly over one percentage point in favor of Harris. While all of these are near misses, it's interesting that all are misses in the same direction, though just barely in the case of RCP. If these were coin flips, the probability of their all erring in the same direction is only one out of sixteen. Thus, it seems likely that, in an election so close―in which the electorate is divided roughly 50-50―this must be a systematic rather than a random error, that is, a bias. Specifically, it's evidence for the "Trump effect" in this election.

As long as our presidential elections are close―and this has been the case since the turn of the century―even the most accurate polls are not going to help predict the results. Unless and until we return to the years of genuine landslides, such as those in 19645 or 19846, polls and even their averages are simply not precise enough to predict a presidential election.

Let's end with some more good news for the pollsters. While the polls suggested that Harris would win by a nose, the "Trump effect"―that is, the underestimate of the former president's support―was less than in previous contests: between two and three percentage points rather than as much as four points7. Given that Trump is constitutionally prohibited from running for president again, this should be the end of the eponymous effect. We saw in 2022 that when Trump himself was not running, the "effect" seemed to have little or no effect8, and Republicans in general don't appear to be affected by it. Even this year, in some of the states that Trump won, Trump-endorsed senate candidates lost9. So, four years from now we won't have to worry about Trump skewing the polls.

Notes:

- This entry is partly based on the following previous entry: "It ain't over till it's over.", 9/23/2020.

- See: Did Trump Win in a "Landslide"?, 11/14/2024.

- "US presidential election results", Reuters, 11/19/2024.

- Ed Kilgore, "What the Harris vs. Trump Polls Got Wrong", New York Magazine, 11/6/2024.

- "United States presidential election of 1964", Britannica, 10/27/2024.

- "United States presidential election of 1984", Britannica, 10/30/2024.

- G. Elliott Morris, "2024 polls were accurate but still underestimated Trump", ABC News, 11/8/2024.

- See: A Post-Election Trump Effect Post-Mortem, 11/19/2022.

- Riley Beggin, "Why did Democrats win Senate races in so many states Trump won? Ticket splitters", USA Today, 11/9/2024.

November 14th, 2024 (Permalink)

Did Trump Win in a "Landslide"?

Some commentators on the recent election are claiming that former president, and now future president, Donald Trump, won in a "landslide". Here, for instance, is a headline from USA Today:

Trump beat Harris in a landslide.

Will his shy voters feel emboldened?1

More predictable is the following headline from the conservative Washington Times:

Trump's landslide win redraws electoral map,

shatters Democratic strongholds2

"Landslide" is, of course, a vague word, so there is no exact number or percentage of votes that defines it. It's also ambiguous in American presidential politics as to whether the alleged "landslide" occurred in the popular vote or in the electoral college. Let's look first at the popular vote.

That vote is still not entirely counted3, but the remaining votes will probably not be enough to change the following analysis. According to the most recent results4, Trump received a little less than 76 million votes and Vice President Kamala Harris got a bit less than 73 million, so that Trump won by about three million votes.

In percentage terms, Trump received a bit more than 51% of the vote and Harris a little less than 49%, so that Trump not only won the popular vote but also a majority of it. However, Trump's margin of victory over Harris was only a bit more than two percentage points, and it's possible that that margin will decrease as additional votes come in from innumerate states.

Conveniently, an article also from USA Today provides some historical context5: it includes both the popular vote margins of victory and electoral college totals for the previous ten president elections. In those ten contests, the only candidate who actually won both the electoral college and the popular vote, but whose margin of victory was less than Trump's, was George W. Bush in 2004 with just over three million votes. Joe Biden beat Trump in the previous election by a margin about twice as large as Trump's this year. So, if Trump's victory was a "landslide", then Biden's was surely an even bigger one.

Similarly, in the electoral college, Trump won 312 votes, which is safely above the 270 needed, and six votes greater than his 2016 win. However, Barack Obama received 365 and 332 in 2008 and 2012, respectively. If at least 312 electoral votes is a "landslide" in the electoral college, then six of the previous ten elections were landslides.

So, if Trump's victory was not especially large in either the popular vote or electoral college, why do some journalists seem to think it was a "landslide"6? One factor is probably the result of youth and inexperience, together with historical illiteracy. Another is shock that Trump not only won but that, unlike 2016, he won both the electoral college and the popular vote.

Notes:

- Charles Trepany, "Trump beat Harris in a landslide. Will his shy voters feel emboldened?", USA Today, 11/6/2024.

- Susan Ferrechio, "Trump's landslide win redraws electoral map, shatters Democratic strongholds", The Washington Times, 11/6/2024.

- I don't know why it takes some states so long to count ballots. It's now over a week since election day, and there's no reasonable excuse for it taking so long, especially when we have computers.

- See: "2024 General Election Results", The Hill, accessed: 11/13/2024.

- Rachel Barber, "How big was Trump's win? How it compares with the past 10 presidential victories", USA Today, 11/6/2024.

- At least one journalist knew better, see: Zachary B. Wolf, "Trump's win was real but not a landslide. Here's where it ranks ", CNN, 11/9/2024.

November 10th, 2024 (Permalink)

Subsiding or Subsisting?

Most of the pairs and triplets of words that we've looked at in this series of entries on easily confused words have been homophones, that is, words that are spelled differently but sound alike. However, there is a smaller class of pairs that neither sound alike nor are spelled alike, yet are still confusible, for example, "perpetrate" and "perpetuate"1: the problem with such pairs is that they are so similar looking as to be easily misread, one for the other, by a quick or casual glance.

The following sentence from a recent newspaper article introduces another such confusion: "The six Israelis were apparently kept in this tunnel system the entire remainder of their lives, subsiding mostly on energy bars, according to the report."2 "To subside" means to sink or lessen3. While I've no doubt that the six hostages who were forced to live on glorified candy bars for months did figuratively sink lower, and their health and strength lessened, nonetheless I don't think that this is what the article's authors meant.

"To subsist" means to survive4, and when used in the phrase "subsist on" it means to barely survive, as in "to subsist on nuts and berries". While I can't prove it, I suspect that the authors of the news report meant to write that the hostages subsisted on energy bars, rather than that they "subsided" on them.

None of the usual reference books I check warns of confusing "subside" for "subsist", which suggests that perhaps it isn't a common confusion. Yet, a quick internet search reveals another example from a webpage for a seller of hiking equipment: "Contrary to popular belief, hikers who engage in extended hiking expeditions are not forced to subside on nuts and berries.5"

Both of these examples go one way, that is, "subside" takes the place of "subsist", rather than the other way around. Specifically, it's the phrase "subsist on" something that seems to cause the confusion. Other than the fact that the words look alike, I can't imagine why this happens.

Since "subsiding" and "subside" are both spelled correctly in the example sentences, a pure spell-checking program won't catch the mistake and, since both words are verbs, even a grammar-checking program is not likely to do so. I tried both of the example sentences in several free online checkers, and not a single one flagged "subside" as an error, so don't count on such programs to save you. In contrast, I had the following exchange with ChatGPT:

Me: Hi, can you help me with an English language problem?

ChatGPT: Of course! I'd be happy to help. What's the language problem you're working on?

Me: Is there anything wrong with the following sentence: The six Israelis were apparently kept in this tunnel system the entire remainder of their lives, subsiding mostly on energy bars, according to the report.

ChatGPT: Yes, there is a small issue with word choice in this sentence. The word "subsiding" is not appropriate in this context. "Subsiding" means to sink, diminish, or decrease, which doesn't fit the intended meaning here. The correct word would be "subsisting," which means to survive or sustain oneself, typically with minimal resources.

Here's the corrected sentence: "The six Israelis were apparently kept in this tunnel system the entire remainder of their lives, subsisting mostly on energy bars, according to the report." Let me know if you need further clarification!6

I'm skeptical about ChatGPT7 but, at least in this one case, it was more useful than dedicated spell-checking programs.

Notes:

- See: Perpetrate or Perpetuate, 7/2/2021.

- "Six slain hostages were likely Sinwar's shields, lived for months on energy bars", The Times of Israel, 10/20/2024.

- "Subside", Cambridge Dictionary, accessed: 11/9/2024.

- "Subsist", Cambridge Dictionary, accessed: 11/9/2024.

- "Backpacking Basics", Vargo, accessed: 11/9/2024.

- "Private Exchange", ChatGPT, 11/10/2024.

- See:

- Are you smarter than an artificial intelligence?, 6/1/2024

- Child's Play?, 7/1/2024

November 2nd, 2024 (Permalink)

Can Jeff Bezos Save The Washington Post?

& Shaken Baby Syndrome on Trial

In case you don't know, Jeff Bezos, the man who made his billions from Amazon, bought the financially ailing Washington Post over a decade ago1. The Post is still ailing financially, having lost $77 million last year2, which isn't pocket change even for Bezos. In addition, the newspaper has lost half its audience in the last four years. Recently, Bezos announced that the paper would not endorse a candidate for president this election, which produced much wailing, rending of garments, and cancelling of subscriptions3. Subsequently, Bezos published the following editorial to defend his decision.

- Jeff Bezos, "The hard truth: Americans don't trust the news media", The Washington Post, 10/28/2024

In the annual public surveys about trust and reputation, journalists and the media have regularly fallen near the very bottom, often just above Congress. But in this year's Gallup poll, we have managed to fall below Congress. Our profession is now the least trusted of all. Something we are doing is clearly not working. …

We must be accurate, and we must be believed to be accurate. It's a bitter pill to swallow, but we are failing on the second requirement.

This is because you're failing on the first. If you see this only as a public relations problem, you'll continue to fail on both.

Most people believe the media is biased. Anyone who doesn't see this is paying scant attention to reality, and those who fight reality lose. Reality is an undefeated champion. It would be easy to blame others for our long and continuing fall in credibility (and, therefore, decline in impact), but a victim mentality will not help. Complaining is not a strategy. We must work harder to control what we can control to increase our credibility.

Presidential endorsements do nothing to tip the scales of an election. No undecided voters in Pennsylvania are going to say, "I'm going with Newspaper A's endorsement." None.

I don't see how Bezos can possibly know this. I certainly would be skeptical that a newspaper endorsement, even that of The Washington Post, would sway many voters, but none at all? Given that Bezos can't possibly know this, why does he insist on it? Many of those upset by Bezos' decision not to endorse Kamala Harris―the chance that The Post would endorse Trump is as close to zero as you wish―are unhappy that the newspaper isn't doing all that it can to elect her, despite the fact its news pages are completely behind her. So, Bezos is trying to convince these people that the non-endorsement won't hurt Harris, and I expect it won't make any difference to the outcome of the election even if a few voters might have been swayed by an endorsement.

What presidential endorsements actually do is create a perception of bias. A perception of non-independence. Ending them is a principled decision, and it's the right one. Eugene Meyer, publisher of The Washington Post from 1933 to 1946, thought the same, and he was right. By itself, declining to endorse presidential candidates is not enough to move us very far up the trust scale, but it's a meaningful step in the right direction. I wish we had made the change earlier than we did, in a moment further from the election and the emotions around it. That was inadequate planning, and not some intentional strategy. …

What really creates the perception of bias is the fact of it in The Post's reporting and not an endorsement that occurs once every four years. Not only will dropping the endorsement not move The Post "very far up the trust scale", it shouldn't. To really bring back trust will require much larger and more substantive changes to the newspaper. A first step in that direction will be not to rehire any employees who quit over the non-endorsement. Similarly for any lost subscribers: Bezos needs to win back the subscribers The Post lost long ago rather than those lost in the last week or so. Bezos has the money, if he's willing to put it where his mouth is, to weather the current loss of subscribers and give the paper a chance to be reformed.

Lack of credibility isn't unique to The Post. Our brethren newspapers have the same issue. And it's a problem not only for media, but also for the nation. Many people are turning to off-the-cuff podcasts, inaccurate social media posts and other unverified news sources, which can quickly spread misinformation and deepen divisions. The Washington Post and the New York Times win prizes, but increasingly we talk only to a certain elite. More and more, we talk to ourselves.

…I will…not allow this paper to stay on autopilot and fade into irrelevance―overtaken by unresearched podcasts and social media barbs―not without a fight. It's too important. The stakes are too high. Now more than ever the world needs a credible, trusted, independent voice, and where better for that voice to originate than the capital city of the most important country in the world? To win this fight, we will have to exercise new muscles. Some changes will be a return to the past, and some will be new inventions. Criticism will be part and parcel of anything new, of course. This is the way of the world. None of this will be easy, but it will be worth it. I am so grateful to be part of this endeavor. Many of the finest journalists you'll find anywhere work at The Washington Post, and they work painstakingly every day to get to the truth. They deserve to be believed.

Nobody deserves to be believed unless they earn it. Currently, the paper endorses Harris on every one of its news pages, and it will take much more than not endorsing her on the editorial page to change the entirely correct perception of bias. I wish Mr. Bezos good luck in attempting to reform The Post―he's going to need it as it will be a very big job.

- Jeff Kukucka & David Faigman, "Shaken Baby Syndrome Has Been Discredited. Why Is Robert Roberson Still on Death Row?", Scientific American, 10/26/2024

In a last-minute effort to save the life of a man on death row, a bipartisan group of Texas legislators has just done something extraordinary: they have unanimously subpoenaed Robert Roberson, convicted in 2003 of killing his daughter based on the now-discredited theory of shaken baby syndrome, to testify before them five days after he was scheduled to be executed, effectively forcing the state to keep him alive.

Roberson is one of many people who have been imprisoned for injuries to a child that prosecutors argue resulted from violent shaking. But research has exposed serious flaws in these determinations, and dozens of other defendants who have been wrongly convicted under this theory have been exonerated. Yet Roberson remains on death row, even as politicians, scientists and others…have spoken out on his behalf. If his execution proceeds, they and many others believe that Texas will be killing an innocent man for a "crime" that never happened.

As our scientific understanding of shaken baby syndrome has evolved over the past 20 years, justice requires that courts reexamine old convictions in light of new findings. This is especially true for Roberson, who would be the first person in the U.S. to be executed for a conviction based on shaken baby syndrome. No matter one's view of the death penalty, the ultimate punishment must be held to the ultimate standard of proof―and Roberson's case falls woefully short of that standard.

The theory behind shaken baby syndrome dates back to the early 1970s, when two medical researchers―Norman Guthkelch and John Caffey―separately published the first scientific papers explaining that shaking an infant can cause fatal internal injuries even absent external injuries. Over time physicians and law enforcement officers, among others, widely began to rely on a triad of symptoms―brain bleeding, brain swelling and retinal bleeding―as definitive proof that someone had abused a child by shaking. To support this theory, researchers cited cases in which a child displayed these symptoms and a caretaker confessed to shaking the child, which ostensibly confirmed the triad as a reliable way to diagnose abuse.

There is no doubt that shaking a child can cause injuries, including those that comprise the shaken baby syndrome triad. Newer research, however, has shown that shaking is not the only way to cause those injuries: They can also result from an accidental "short fall" (e.g., falling off a bed) as well as from other medical causes (e.g., pneumonia, improper medication)―all of which were true of Roberson's daughter. In fact, a 2024 study found that the injuries historically used to diagnose shaking are actually more likely to result from accidents than from shaking. In short, modern science understands that the presence of these symptoms does not necessarily mean that a child was abused, nor does their absence mean that they were not abused.

Why did clinicians wrongly trust this triad of symptoms for so long? The short answer is that correcting misconceptions requires a feedback loop that is often lacking in child abuse investigations. When a doctor diagnoses a living adult and prescribes a treatment, the effectiveness of that treatment provides feedback on the correctness of their diagnosis; if the treatment proves ineffective, doctors can learn from this misdiagnosis and adjust future diagnoses accordingly. Such feedback, however, is not always sufficient; for instance, doctors practiced bloodletting for centuries because it was generally accepted and seemed to work for some patients, though it was an illusory correlation. With respect to shaking, doctors rarely learn whether a child was actually shaken because the child is typically deceased or unable to articulate what happened, and thus doctors rarely receive feedback that the triad led to an incorrect diagnosis. …

Science is constantly evolving, and when it reveals a past mistake, we do not simply resign ourselves to it; we take corrective action. Our legal system should be no different. When Robert Roberson was convicted, the injury triad was widely accepted as proof of shaking―but as science has progressed, that is no longer the case. The law's guarantee of due process must account for such progress, especially when a person's life literally depends on it. …

The evidence for Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS) was always shaky4, if you'll forgive the pun, and the evidence against individuals, such as Roberson5, is often based entirely upon that shaky evidence. There usually is no direct evidence―such as a confession, photos or video, or an eyewitness―that the baby was shaken. So, the only evidence of a crime is medical evidence. If the symptoms supposedly proving SBS may, in fact, be caused by other things than shaking―such as short falls or certain diseases―then death may be the result of an accident or illness rather than homicide. Do we want to execute people when there's reasonable doubt as to whether a crime even occurred, let alone that the accused is guilty of it?

Notes:

- Benjamin Mullin & Katie Robertson, "A Decade Ago, Jeff Bezos Bought a Newspaper. Now He's Paying Attention to It Again.", The New York Times, 7/22/2023.

- Oliver Darcy, "The Washington Post publisher disclosed the paper lost $77 million last year. Here's his plan to turn it around", CNN, 5/23/2023.

- Erik Wemple, "What happened to all those subscriptions?", The Washington Post, 11/1/2024.

- Deborah Tuerkheimer, "Shaken baby syndrome is not definitive proof of child abuse", New Scientist, 9/19/2017.

- For details of the case against Roberson, see: Kayla Guo, "There are warring depictions of Robert Roberson's murder case. Here's what to know.", Texas Tribune, 10/29/2024.

Disclaimer: I don't necessarily agree with everything in these articles, but I think they're worth reading as a whole.