Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

WEBLOG

November 30th, 2019 (Permalink)

The State of the Debates, Scientific Graphs, Fact-Checking Books & Autism Profiteering

- Edward Morrissey, "Same schtick, different debate", The Week, 11/21/2019.

Wednesday's Democratic presidential debate followed a familiar recipe: Put 10 candidates on a stage, fold in four questioners, and mix for two hours. This combination reliably produces lots of platitudes, which make for light eating but provide next to no substance at all. … The fault for this does not lie entirely with the candidates, or the questioners, or even with the television cameras or the live audiences. The Democratic National Committee continues to insist on a full-stage format for these debates that ends up transforming them into game shows, and the fifth debate was no exception. … That's not to say the participants in these debates don't bear some responsibility for the lack of substance and educational value. … When asked more specific questions about policies or previously announced plans, candidates asked viewers to read their web site while offering up canned sound bites from their stump speeches. … Thanks to a lack of any specifics, the most that can be said on the issues is that everyone on stage generally agrees with everyone else, whether it comes to abortion rights (good), voting rights (good), climate change (bad), white supremacy (also bad), guns (very bad), and especially Trump (very, very bad).

I don't have anything to add about this month's "debate" because it was just more of the same old thing. I'm getting bored with these pseudo-debates, and I'm not alone. Viewership for this one was the lowest of any so far:

- Mark Joyella, "6.6 Million Watch MSNBCís Coverage Of Fifth Democratic Debate", Forbes, 11/21/2019.

Compared to previous debates this year, the Wednesday night debate was down, both compared to the most recent debate last month―and to the first debates of the Democratic primary campaign. The ratings dropped from the last Democratic debate, in October, which aired on CNN and drew a total audience of 8.3 million viewers―which itself was down from earlier debates in the 2020 campaign, with the first of two nights of the first debate drawing 15 million viewers across three networks: NBC, MSNBC and Telemundo. The third debate, which aired on ABC and Univision, drew 14 million.

At this rate, the eighth one will have zero viewers. The Democratic Party needs to change this show or cancel it due to low ratings.

- Betsy Mason, "Why scientists need to be better at data visualization", Knowable Magazine, 11/12/2019.

…[S]cience is littered with poor data visualizations that confound readers and can even mislead the scientists who make them. Deficient data visuals can reduce the quality and impede the progress of scientific research. And with more and more scientific images making their way into the news and onto social media―illustrating everything from climate change to disease outbreaks―the potential is high for bad visuals to impair public understanding of science.

- Kelsey Piper, "A new book says married women are miserable. Don't believe it.", Vox, 6/4/2019.

People trust books. When they read books by experts, they often assume that they're as serious, and as carefully verified, as scientific papers―or at least that there's some vetting in place. But often, that faith is misplaced. There are no good mechanisms to make sure books are accurate, and that's a problem. … There are a few major lessons here. The first is that books are not subject to peer review, and in the typical case not even subject to fact-checking by the publishers―often they put responsibility for fact-checking on the authors, who may vary in how thoroughly they conduct such fact-checks and in whether they have the expertise to notice errors in interpreting studies, like [Naomi] Wolf's….

- Anna Merlan, "Jenny McCarthy's Autism Charity Has Helped Its Board Members Make Money Off Dangerous, Discredited Ideas", Jezebel, 3/20/2019.

Camel's milk. B12 lollipops. Hyperbaric oxygen chambers. "Ion-cleansing" foot baths. Chelation therapy. Gluten-free diets. Casein-free diets. Massive doses of nutritional supplements. All of these products and services have two things in common. First, mainstream (and widely trusted) medical bodies don't recognize them as a reputable or effective treatment for autism. Second, they're all recommended by―and in some cases sold outright through―Generation Rescue, a charity for autistic kids and their families whose board president and most famous face is actress Jenny McCarthy.

November 29th, 2019 (Permalink)

Junk Food Research

Last month, a major peer-reviewed study questioned advice that most people should eat less red and processed meats, concluding that the evidence backing long-standing recommendations is weak. The study…sparked an international media frenzy and yet another round of consumer whiplash. It highlighted why diet studies are the frequent butt of jokes: One day coffee is healthy, the next it's not; red wine is good for your heart, or maybe not; cheese is either a healthy source of protein and calcium, or a dangerous overdose of fat and salt.1

It appears that just about everyone now realizes that research on food is in a bad way, as evidenced by this article. We seem to have made little progress in understanding food, diet, and nutrition in at least the last half-century, since much of what we were told in that time has now been taken back. If anything, the situation is now worse because of the spread of misinformation. Unfortunately, the article proposes a treatment that would make the disease worse.

I have many criticisms to make of this article, starting with its title: "How Washington keeps America sick and fat". Washington isn't to blame for illness or obesity, and the article itself does not make a good case that it is. Of course, an editor may be responsible for this tabloid-style headline. However, I still recommend reading it, and my subsequent criticisms may not make much sense unless you do.

It starts out by claiming that illness related to diet is a growing problem:

Diet-related illnesses like obesity, Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure are on the rise while heart disease remains the leading cause of death. Treating these intertwined epidemics is a top driver of ballooning U.S. health care costs.1

High blood pressure and heart disease are related to both age and obesity, so they're diet-related to the extent that people get enough food to live to old age or become obese. Moreover, obesity is also related to type 2 diabetes, and both are related to diet, but more to the amount that people eat than to specific foods. Throughout most of history it was difficult to get enough to eat to live to old age, let alone to get fat, and it still is in some parts of the world. So, these problems are symptoms of affluence in that food is inexpensive and abundant in America, and people live long enough to suffer the medical problems of old age2.

The article goes on to say that poor diet is the "root cause" of many of these illnesses, but gives no evidence to support this claim. I suppose that people who eat so much they become obese can be said to be suffering from "poor diets", but what can more nutrition research do about it? One of the few things we do know about nutrition is that if you take in more calories than your body uses, your body will store the excess as fat.

The article spends a good deal of space arguing that nutrition research is underfunded by the federal government, but it does so without putting it into context. How much should be spent on food research? You can't determine how much to spend on such research by simply looking at how much is spent in absolute terms, or by comparing it to how much is spent on something else, which is all that the article does. How much would it be useful to spend on it? Until we have answers to such questions, we can't know whether we're spending too little, too much, or just enough.

Despite arguing for spending more on food research, the article admits that much of what is currently spent is for research of doubtful value. Here's its explanation of how this comes about:

A major reason why the nutrition science field is in turmoil is because the science itself is so complicated. Researchers can't feasibly lock up people for decades and meticulously track their diets. Even if they could, people eat so many different foods in different combinations that isolating the impact of one variable is incredibly difficult. … The gold standard for most medical research is randomized controlled trials. Researchers assign people to two or more groups: One that will get the intervention, in this case a particular type of food or diet, and another that will not, known as a control group. This approach works well for determining whether a drug is effective, but is not as straightforward in nutrition studies. Humans don't tend to stick to specific diets over the course of weeks, months or even years, making it difficult to parse out how eating oatmeal for breakfast―or any other food―affects our health.1

Doing good research is no doubt costly, time-consuming, and difficult, but that is no excuse for doing bad research. No research at all would be better than bad research for the reason that being ignorant is better than being misinformed. We've been misinformed on a series of food issues for the last half-century or so, and many people changed how they ate based on this misinformation. For instance, I grew up eating margarine instead of butter, not because margarine was cheaper, but because it was supposedly better for you. We're now told that the kind of margarine I ate as a child is actually worse for you than butter3.

If much of the government money now spent on nutrition research produces misinformation such as that about butter vs. margarine―or salt, for another example4―how is that going to be fixed by spending even more? To increase funding for such research would appear to reward current practices, and just get us more of the same. At the very least, if the government is going to increase spending, it should insist on funding experimental, rather than observational, studies.

Notes:

- Catherine Boudreau & Helena Bottemiller Evich, "How Washington keeps America sick and fat", Politico, 11/4/2019.

- For the claims made in this paragraph, see:

- "Family History and Other Characteristics That Increase Risk for High Blood Pressure", CDC, 7/30/2019.

- "Family History and Other Characteristics That Increase Risk for Heart Disease", CDC, 7/30/2019.

- "Behaviors That Increase Risk for High Blood Pressure", CDC, 7/7/2014.

- "Conditions that Increase Risk for Heart Disease", CDC, 2/6/2019.

- "Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes", National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 11/2016.

- See, for instance: "Butter vs. Margarine", Healthbeat, accessed: 11/21/2019.

- Melinda Wenner Moyer, "It's Time to End the War on Salt", Scientific American, 7/8/2011.

November 28th, 2019 (Permalink)

Thank You!

Thanks to everyone who has read and supported this site during the past year! The Fallacy Files is an Amazon Associate and, with the holidays upon us, please consider doing any shopping at Amazon by way of one of the links from this site. It won't cost you a penny extra and will help keep the site going for another year. If you are feeling generous this holiday season and wish to support the site in a more direct way, you can always donate via the PayPal button in the navigation pane to your right. Your continued support is appreciated!

Update (4/23/2021): The Fallacy Files is no longer an Amazon Associate.

November 27th, 2019 (Permalink)

A Knights of the Round Table Thanksgiving

Gwen Knight was in charge of assigning places at the Thanksgiving dinner table for members of her extended family. In order to avoid incidents such as happened last Thanksgiving, when one drunken Knight challenged another to a sword fight, she decided to ask each of the invited family members in advance for one other relative they would like to be seated next to, and whether they preferred that family member should be seated on their left or right.

The dinner was to take place at a big round table in her dining room that could comfortably sit seven people. The requested seating arrangements were as follows (Gwen included her own preference in the list):

Arthur wished for Percy to be seated on his right.

Boris wanted Percy to sit on his left.

Kay desired to sit at Arthur's right hand.

Dan requested that Gwen sit next to him on the right.

Eric wanted Boris to sit on his left.

Percy hoped that Eric would sit to his right.

Gwen wished that Kay would sit at her right hand.

Oh, dear! It would not be possible to sit all of the Knights according to their requests since some contradicted others, but Gwen wanted to sit as many as possible as they wished. How many of the seven requests can be accommodated, and what is the resulting seating arrangement?

Solution to a Knights of the Round Table Thanksgiving: Five of the seven requests are the maximum possible to honor. To see this, note that Arthur requested that Percy be seated on his right, but Kay also wants to sit there, and Gwen wants Kay to sit to her right. If Kay gets what she wants, then both Arthur and Gwen will be disappointed. Therefore, it's better to disappoint Kay. Similarly, Boris wants to sit to the right of Percy, but Percy wants Eric to sit there, while Eric himself prefers to sit to the right of Boris. Again, it's better to disappoint Percy rather than both Boris and Eric. So, both Kay and Percy will have to be disappointed, but the other five diners can be seated as they requested. The resulting seating arrangement is as follows, starting with Arthur and moving right: Arthur, Percy, Boris, Eric, Dan, Gwen, and Kay.

Disclaimer: This puzzle is a work of fiction. Names, characters, and events are the products of the author's warped imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is highly unlikely and purely coincidental.

November 12th, 2019 (Permalink)

Rule of Argumentation 101: Attack or defend claims!

This rule is an extension of rule 3, namely, to focus on claims and arguments. That rule did not go into much detail on how to do this, but this one and the next go into more detail. This rule deals with the first part of rule 3, that is, focusing on claims.

The previous rule admonished you to come to an agreement with your partner in argumentation on the nature of your disagreement. Once you have identified the point of disagreement, then you should make your arguments relevant to that proposition. Under this rule, I'm going to use the word "claim" to refer to any statement or proposition, such as the point of disagreement, either advanced or denied by you or your partner.

By "attack or defend claims", I mean that you should focus your arguments on the claims that are made by you or your partner. To "attack" a claim is to present other claims that tend to show the claim false or at least less probable, whereas to "defend" one is to make claims that support its truth or make it more probable. In other words, you will be making arguments2 either for or against claims. If the claim in question is the point of disagreement between you and your partner in argumentation then, since you two disagree, either you think that the point is true or at least probable whereas your partner thinks that it is false or improbable. If you think the point is false, then your job is to attack it, whereas if you think it true you should defend it.

In attacking claims, you're most likely to miss the target by aiming your arguments at something close to it, but nevertheless distinct. Claims are distinct from their motivations, histories, and the effects on people of holding them. However, such matters are so closely associated with the claims that it is easy to mistake them for the claims themselves. In order to keep your arguments on target―that is, relevant―distinguish claims from the following:

- Motivation: A claim is a sentence that is either true or false, whereas a motivation is not a sentence but a psychological state. Everyone who makes or denies a claim has some psychological reason for doing so, but that motivation is not the same as the claim itself. Moreover, another person who makes the same claim will have a distinct psychological motive for doing so, based on that person's unique personality. There is always a temptation to direct your arguments against what you take to be your partner's motivations for advancing or attacking a claim, but to do so misses the target.

Furthermore, it's very easy to misunderstand your partner's motivation, since you can't read minds. If you do misread your partner and attack the wrong motivation, your partner will be upset, just as you would be if your partner did that to you. This has a tendency to turn a rational discussion into a personal quarrel. Remember to play the ball, not the player!

- History: Every claim has a history, such as who was the first to advance it, who attacked it, what groups supported or opposed it, and so on. All of this history can be interesting and useful, but it is distinct from the claim itself. Some claims with disreputable histories have turned out to be true, just as some with noble lineages are false. For instance, the notion that the Sun revolves around the Earth was believed by most people and even supported by astronomers until Copernicus. So, the history of a claim is distinct from its truth or falsity.

- Effects: By the "effects" of a claim I refer to the effects on people of belief or disbelief in it. Some false beliefs may have beneficial effects on those who believe them; for instance, belief in the Tooth Fairy may make children feel better about losing teeth than they otherwise would. Similarly, some true beliefs may have bad effects on us, such as the knowledge of the death of a loved one. Thus, the fact that a claim may make us happy or sad, or lead us to behave better or worse, is distinct from its truth or falsity.

To sum up, claims should stand or fall on the basis of the strength of the arguments for or against them, and not based on irrelevancies such as the motivation for making them, their history, or their effects on people. How to judge the strength of such arguments will be the subject of the next rule.

Next Month: Rule 11

Notes:

- Previous entries in this series:

- Rule of Argumentation 1: Appeal to reason!, 12/14/2018.

- Rule of Argumentation 2: Be ready to be wrong!, 1/26/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 3: Focus on claims and arguments!, 2/13/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 4: Be as definite as possible!, 3/8/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 5: Be as precise as necessary!, 5/29/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 6: Defend your position!, 7/7/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 7: Aim at objectivity!, 8/9/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 8: Consider all the evidence!, 9/19/2019.

- Rule of Argumentation 9: Agree about what you disagree about!, 10/20/2019.

- There's an ambiguity here that may be confusing: one sense of "argument" is the whole discussion or debate between you and your partner, and another is the logical sense of an "argument" as a series of propositions meant to support a conclusion. I'm using the logical sense here. Also, I usually use the longer word "argumentation" for the first sense.

November 8th, 2019 (Permalink)

The smaller the print, the more important the message.

I don't follow British politics since I have enough trouble keeping up with politics in America. Luckily, I don't have to, since our correspondent in the United Kingdom, Lawrence Mayes, is on the job. He emails:

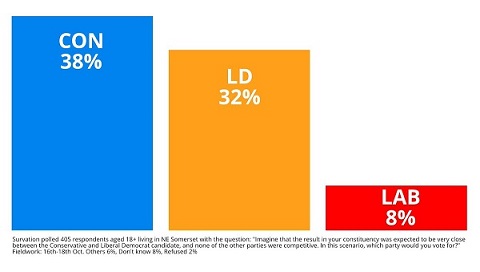

In the UK, we're having a general election. There are two main parties (Conservative and Labour) and around eight others. The largest (in England, that is) of the others is the Liberal Democratic Party.The Liberal Democrats have published a graphic showing how close they are to beating the Conservatives in the North East Somerset constituency1. Pretty close, hey? But how close? At the last election the Liberal Democrats performed pretty poorly coming third behind the Labour candidate. What's changed? Not a lot, in fact, because if you read the very small print at the bottom2, you will see that the question asked was:

"Imagine that the result in your constituency was expected to be very close between the Conservative and Liberal Democrat candidate, and none of the other parties were competitive. In this scenario, which party would you vote for?"So the respondents were asked to imagine something that was almost certainly untrue and produce an answer based on that dubious fiction. No wonder the result was as it was. Of course, the same question asked in almost any constituency would likely produce a similar result where the Conservative candidate was most popular. This happens because the winning candidate often is elected with less than 50% of the votes (there are usually at least four parties represented in each constituency). A Labour voter is highly unlikely to switch their support to the Conservative candidate just because the Labour candidate was unlikely to win; unless they decided to abstain, they would more likely tactically switch their vote to whichever candidate would best challenge the Conservative for the seat, in this imaginary case they are told that is the Liberal Democrat―hence the result.

Notes:

- BathNES Lib Dems, "If we work together, and back @nickcoatesnes we will beat Jacob Rees-Mogg in North East Somerset #VoteNickCoates #StopMogg", Twitter, 10/30/2019. See the bar graph, above.

- "Survation polled 405 respondents aged 18+ living in NE Somerset with the question: 'Imagine that the result in your constituency was expected to be very close between the Conservative and Liberal Democrat candidate, and none of the other parties were competitive. In this scenario, which party would you vote for?' Fieldwork: 16th-18th Oct. Others 6%, Don't know 8%, Refused 2%"

November 4th, 2019 (Permalink)

False Alarm

Guess who the following passage describes:

…[T]he man who claimed to be the nation's leader had not been elected by a majority vote and the majority of citizens claimed he had no right to the powers he coveted. He was a simpleton, some said, a cartoon character of a man who saw things in black-and-white terms and didn't have the intellect to understand the subtleties of running a nation in a complex and internationalist world. His coarse use of language…and his simplistic and often-inflammatory nationalistic rhetoric offended the aristocrats, foreign leaders, and the well-educated elite in the government and media. … To deal with those who dissented from his policies, at the advice of his politically savvy advisors, he and his handmaidens in the press began a campaign to equate him and his policies with patriotism and the nation itself. National unity was essential…and so his advocates in the media began a nationwide campaign charging that critics of his policies were attacking the nation itself. Those questioning him…it was suggested…were aiding the enemies of the state by failing in the patriotic necessity of supporting the nation….1

This passage is part of a longer article which is really about two people: the first is Adolf Hitler and the second is an American president. It's supposed to be a factual description of Hitler which also calls to mind the man who was president at the time of writing. The purpose of such a comparison is, of course, to suggest that the president is a danger to democracy and a potential dictator.

If reading the above passage made you think of President Donald Trump, I'm not surprised, since that's exactly what I intended. I selected such phrases as "not…elected by a majority vote", "a cartoon character of a man", "[h]is coarse use of language", and the reference to "enemies of the state" all because they would suggest Trump.

But look down at the Notes, below, and notice the date of the article excerpted above. 2003! That's over thirteen years before Trump became President. Was the author of the article psychic? No. Who was President of the United States in 2003? George W. Bush. The article that I quoted was meant to suggest that Bush was the second coming of Hitler.

You may complain that I cherry-picked the details from the original article that could apply to Trump, ignoring the more Bush-specific ones, such as a reference to "his political roots in a southernmost state". This is true, but that's the whole point of the exercise, since it's exactly what the author of the original article did: choose historical similarities between Hitler and Bush and ignore the many dissimilarities.2

Of course, if Bush had really been a wannabe dictator, he'd still be president instead of Trump, or at least he'd have made some effort not to leave office or to install a crony in his place. Instead, we got eight years of Barack Obama. Some dictator. However, maybe this time all those warning us that the next Hitler is coming will turn out to be right.

For example, earlier this year former Democratic presidential candidate Robert "Beto" O'Rourke, referred to:

…[T]he rhetoric of a president [Trump] who not only describes immigrants as rapists and criminals but as animals and an infestation. Now, I might expect someone to describe another human being as an infestation in the Third Reich. I would not expect it in the United States of America….3

The first sentence in this quote contains two contextomies, both of which have been previously debunked, so I won't go into the details: "immigrants as rapists", which I've discussed previously4, and the claim that Trump called immigrants "animals", which has been debunked by Snopes5. O'Rourke went on in the same speech to accuse Trump of "saying that neo-Nazis and Klansmen and white supremacists are very fine people"3, which is yet another contextomy6. If Trump is as much like a Nazi as O'Rourke seems to think, why does O'Rourke have to keep quoting out of context?

The article continues:

O'Rourke's comparison on Thursday night came in response to a question about how he would take on Trump if he's the 2020 Democratic nominee. He said he would seek to "pull this country together around the work that's ahead." He vowed to jettison the "pettiness and meanness and personal attacks," arguing that Democrats may lose if they try to match Trump's approach because Trump is too "gifted" at that style of campaigning.3

I hope the remaining candidates will do as he said, not as he did, and jettison the petty, mean personal attacks. Now, I don't call attention to this to pick on O'Rourke, who's already dropped out of the race, but to point to a perennial claim that we hear every time there's a Republican president7. In addition to those who accused Bush of being a Nazi, we've also seen that Nixon got the same treatment8. If it isn't O'Rourke saying it, I'm sure there are and will be others, and I don't want to have to point it out every time.

The only excuse I can see for playing the Hitler card9 is as a warning of an immediate threat to democracy from a candidate or president intending or attempting to establish a dictatorship. It would be comforting to think that such a thing could not happen in the United States of America, but history suggests otherwise. So, we need to be on our guard against such a possibility, and an appropriate warning might help us to avoid such a calamity.

However, a smoke alarm that went off every day whether there's a fire or not would be as useless as one that never went off even when there was one. If people keep predicting that every Republican president is the next Hitler, maybe eventually they'll be right, but because of all the false alarms no one will be paying attention.

Notes:

- Thom Hartmann, "When Democracy Failed: The Warnings of History", Common Dreams, 3/16/2003.

- I critiqued this article at the time it first appeared, see: Playing the Hitler Card, 3/22/2003. Some of Hartmann's historical claims sound suspect to me, but this is a logic check, not a history check. Moreover, some are so slanted that it's difficult to be sure what he means. The most egregious example is the repeated use of the phrase "Middle Eastern ancestry" which is supposed to mean "Jewish" when applied to Hitler and "Arab" when applied to Bush!

- Sahil Kapur, "In Iowa, O'Rourke Says Some Trump Rhetoric Echoes Nazi Germany", Bloomberg, 4/4/2019.

- For details, see: Meet the Press, 9/25/2018.

- Dan MacGuill, "Did Trump Echo Hitler by Calling Undocumented Immigrants 'Animals'?", Snopes, 5/21/2018.

- See: Donald Trump, Familiar Contextomies.

- When there's a Democratic president or presidential candidate, he or she is always accused of being a socialist rather than a Nazi. This is as absurd a charge as playing the Hitler card, since the Democrats would never nominate a socialist for president―now, would they?

- See: Passage of Propaganda, 7/28/2017.

- See: The Hitler Card.

November 2nd, 2019 (Permalink)

Know-It-All Society

Title: Know-It-All Society

Subtitle: Truth and Arrogance in Political Culture

Author: Michael Patrick Lynch

Date: 2019

Quote: "This book is about…how we ought to believe. Or to put it more precisely, it concerns how we should go about the business of acquiring and maintaining our political convictions.1"

The title of the new book this month is just Know-It-All Society: no "the" for some reason―did the printers run out of definite articles? Anyway, the subtitle is perhaps more revealing about the book's topic.

The author, Michael Patrick Lynch, is a professor of humanities who has written a number of previous books on truth, the internet, and rationality in politics. I'm afraid that I haven't read any of them, but they may represent a good foundation for the present one.

By "know-it-all", Lynch seems to be referring to the kind of person who acts as though he or she knows everything, that is, it's the pejorative sense of "know-it-all". So, a "know-it-all society" would, I guess, be one in which a lot of people behave like know-it-alls. Moreover, Lynch seems to think that our current society is a know-it-all one, or is at least moving in that direction; he writes:

Judging by the tenor of our political discourse, our answer to the question of how we should believe seems to be: as dogmatically as possible. Recent data suggests that people from different sides of the political spectrum, at least in the United States, still agree more than they disagree on many issues. But this same data also shows that, increasingly, we regard the other party with suspicion―as dishonest, uninformed, and downright immoral. The idea that we should listen to their views seems unthinkable. … The Right sees liberals as arrogant know-it-alls, while the Left retorts that this is precisely the description of the person the conservatives elected president of the United States. But maybe both sides have a point. Maybe all of us, in a certain sense, are know-it-alls, and thatís part of the problem.2

Well, I don't think I'm a know-it-all. However, there's no doubt a problem of over-confidence, which is a cognitive bias of ignorance about ignorance, or meta-ignorance. In other words, the big problem isn't so much ignorance, as we're all ignorant about many things, but the failure to appreciate one's own ignorance. That is, people are often ignorant of their own ignorance: they don't know what they don't know. Or, as a familiar saying puts it: "It ain't so much the things we don't know that get us into trouble, it's the things we know that just ain't so."3

I agree with the following:

It is tempting to think that these problems can be handled with technical, policy-driven solutions: reimagining our digital platforms, or passing new legislation, or teaching people more facts about civics. And without a doubt, those things are terribly important. But at the end of the day, dealing with our attitudes toward truth and conviction wonít be solved just by teaching people more facts when we donít agree on what counts as a "fact." The problem of how to deal with the spread of dogmatism and the politics of arrogance is not a technical problem; it is a human problem. If we want to solve it, we have to change how and what we value; we must change our attitudes.4

So, one thing that is needed is more of the intellectual virtue of humility, that is, the recognition that we don't know it all, that we can learn from people who disagree with us, and that changing our minds doesn't harm us.

Notes:

- P. 1, emphasis in the original. Subsequent citations of just page numbers are to the new book.

- P. 2.

- This saying is frequently attributed to Mark Twain, but seems to trace back to Josh Billings. See: Ralph Keyes, "Nice Guys Finish Seventh": False Phrases, Spurious Sayings, and Familiar Misquotations (1993), p. 74. See also: "It Ain't What You Don't Know That Gets You Into Trouble. It's What You Know for Sure That Just Ain't So", Quote Investigator, 11/23/2018.

- P. 4.

Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month | Top of Page