WEBLOG

Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

October 28th, 2009 (Permalink)

Check it Out, Too

Britain's Guardian newspaper has a fascinating history of the birth and growth over the last ten years of the estimate of the number of prostitutes trafficked into the U.K.

The number started small but grew with every step of its spread. This is similar to the old game of "telephone", in which a message is whispered into the ear of a person at the front of a line, who then whispers it to the next person in line, and so on to the end of the line. The point of the game is that the message at the end is very different than the original message, being distorted in the process of transmission. However, one difference in this case is that there seems to have been a definite bias to the distortion. If the distortions were simply due to random errors of transmission, one would expect there to be as many errors tending to diminish the number as to increase it, but that's not what happened.

What could explain this kind of statistical inflation? Suppose that each person in the game of telephone has a motive to exaggerate the number they hear. Interest groups have an interest in using big numbers to raise awareness of a problem, and raise money to deal with it; news media have an interest in using big numbers to get bigger ratings or sell more newspapers and magazines; politicians have an interest in using big numbers to get votes and pass legislation. Unfortunately, few players of the game are strongly motivated to get the numbers right. To quote the Numbers Guy:

…[W]ith sensitive issues such as this one, it can be hard to find voices on the other side; after all, no one who wants accurate numbers wants to be seen as supporting sex trafficking.

Read the whole thing.

Sources:

- Sign, Signspotting

- Carl Bialik, "Another Exaggerated Sex-Trade Stat", The Numbers Guy, 10/23/2009

- Nick Davies, "Prostitution and trafficking―the anatomy of a moral panic", Guardian, 10/20/2009

October 25th, 2009 (Permalink)

Always Read the Fine Print

Ben Goldacre's latest Bad Science column deals with a slanted debate about a slanted movie:

You may remember the Aids denialist documentary House Of Numbers…a film which suggests that HIV doesnít cause Aids, but antiretroviral drugs do, or poverty, or drug use, but HIV probably doesnít exist, diagnostic tools donít work, and Aids is simply a spurious basket diagnosis invented to sell antiretroviral medication for a wide range of unrelated problems, and the treatments donít work either. …Christine Maggiore appears many times in the film, talking emotively, explaining her choice not to take Aids medication, and that this is why she is alive.

Christine Maggiore is dead…. The film tells you that but in tiny letters at the very end and it says no more. She died of pneumonia aged 52. And her daughter died of untreated Aids aged 3. Because of her beliefs about Aids, Christine Maggiore did not take medication which has been proven to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to her unborn child during pregnancy. Her daughter, Eliza Jane, was not tested for HIV during her short life. Before she died. Of Aids.

Check it out.

Sources:

- "Sign Language: Read the small print", Telegraph

- Ben Goldacre, "Aids Denialism at the Spectator", Bad Science, 10/24/2009

October 24th, 2009 (Permalink)

Q&A

Q: I've been hearing this sort of argument made recently by right-wing pundits:

Obama is a good speaker.

Hitler is a good speaker.

[More or less implied conclusion:] Obama is Hitler (or like Hitler).

The same type of argument might be made in regard to other characteristics:

Obama wants to nationalize big business.

Hitler nationalized big business.

Therefore, Obama is like Hitler.

I realize that these are not quite genuine formal syllogisms, and I realize that the first example depends on opinion (perhaps some think Obama or Hitler are not good speakers) and that the second example contains untrue premises (Hitler did not nationalize big business; Obama does not want to nationalize big business), but, regardless, some people are making these sorts of arguments anyway.

My question, however, is not whether or not these arguments are valid (I know they are not), but, rather, my question is, what is the name of this sort of fallacy?

The closest type I have been able to identify is the Fallacy of the Undistributed Middle. It doesn't quite fit the above examples, however, because the Fallacy of the Undistributed Middle seems to rely on the word "All," in which case the following would be a better example of the Fallacy of the Undistributed Middle:

Obama is a good speaker.

All Nazis are good speakers.

Therefore, Obama is a Nazi.

Clearly, this is an example of the Fallacy of the Undistributed Middle.

But what about the first two examples I gave you? Are they, too, Fallacies of the Undistributed Middle; or are they some other type of fallacy (and if so, which)? Or are they merely badly written?―Shane K. Bernard

A: It's better to view these arguments not as categorical syllogisms, but as arguments by analogy, that is, arguments whose premisses state that two things are alike in certain respects, and which conclude that they will be alike in some other respects. Analogical arguments are inductive, rather than deductive like categorical syllogisms. Analogical arguments are fallacious when the analogy drawn is either weak, superficial, or question-begging.

More specifically, this is a version of the Hitler Card argument which draws a comparison between someone and Hitler. It appears that we live in a political and rhetorical environment where every president of the United States will sooner or later―probably sooner―be compared to Hitler. During the previous presidency there were many claims that Bush was a would-be Hitler, and I documented a few of the more outrageous and ridiculous ones on this weblog (see the Resources below).

Of course, Obama is a good speaker. Bush had his moments too, though he was poor at speaking extemporaneously, as is Obama. However, anyone who rises to our highest political office is very likely to be an effective speaker, so to that extent every president will have something in common with Hitler. Moreover, if you go searching for similarities between any two people, you're bound to find some.

So, it's just about inevitable that Obama will come in for his share of abuse, and the only real change will be in where the abuse is coming from. It would be nice if the political right would not copy the left's bad behavior toward the previous president, but it's more likely that they will think that turnabout is fair play, even though two wrongs don't make a right. Then, of course, the left will take their revenge on the next Republican president, and so on ad nauseum.

I suppose that it's also expecting too much, now that Bush has left the presidency, to hope that some of those who made the Bush-Hitler linkage would admit that they were wrong. Why didn't he declare martial law? Why didn't he suspend the election? Why didn't he make himself into the dictator that they seemed to think he wanted to be? If Bush was a wannabe dictator, he was a poor one.

Resources:

- Playing the Hitler Card, 3/22/2003

- Springtime for Hitler Analogies, 1/7/2004

- Reader Response, 9/3/2009

October 21st, 2009 (Permalink)

In the Mail

David B. Grant's Joseph Spider and the Fallacy Farm.

October 19th, 2009 (Permalink)

The Black Hole of Sedona

I heard about the following incident when it happened over a week ago, but I didn't realize who organized it until today:

James Arthur Ray led a group of more than 50 followers into a cramped, sauna-like sweat lodge in Arizona last week by convincing them that his words would lead them to spiritual and financial wealth.The mantra has made him a millionaire. People routinely pack Ray's seminars and follow the motivational guru to weeklong retreats that can cost more than $9,000 per person. But Ray's self-help empire was thrown into turmoil when two of his followers died after collapsing in the makeshift sweat lodge near Sedona and 19 others were hospitalized.

…[H]is technique is not just motivational speaking. It's a combination of new age spiritualism, American Indian ritual, astrology and numerology. The sweat lodge experience was intended to be an almost religious awakening for the participants.

Ray uses free seminars to recruit people to his expensive seminars, starting with $4,000 three-day "Quantum Leap" workshops and moving on to the weeklong $5,300 "Practical Mysticism" events and the $9,000-plus "Spiritual Warrior" retreats like the one that led to the sweat lodge tragedy.

… He soared in popularity after appearing in…[the] Rhonda Byrne documentary "The Secret," and he later was a guest on "The Oprah Winfrey Show"….

Ray is also one of the many "co-authors" of Byrne's companion book for "The Secret", and is listed there as a "philosopher". As I noted in my review of that book, none of the so-called "philosophers" listed as "co-authors" appears to have any philosophy credentials, and Ray is no exception. Philosophers aren't licensed, so anyone can claim to be one.

A third person has died since the above report was written. If you ever wonder where's the harm in silly books such as The Secret endorsed by silly celebrities such as Oprah, here's your answer.

Sources:

- Felicia Fonseca & Bob Christie, "Sweat lodge deaths cast negative spotlight on guru", Arizona Daily Sun, 10/17/2009

- Lynn LaMaster, "3rd Person Dies―A Comprehensive Report on Sweat Lodge Event", Prescott eNews, 10/19/2009

Resource: Book Review: The Secret

October 12th, 2009 (Permalink)

A Third Puzzling Picture

The only clue the police have to a murder is a blurry photograph on a cell phone camera. They question a woman who might be able to identify the killer in the picture: "Who is this man, Mrs. Murphy?" There was a long pause as the woman looked intently at the photo. Finally, she answered: "This man's son is my daughter's father's son". After that, she refused to answer any further questions. For the third time, the police come to you for help: If the witness spoke truly, who is the murderer?

Previous Puzzling Pictures:

- The Puzzling Picture, 7/13/2009

- Another Puzzling Picture, 7/28/2009

October 6th, 2009 (Permalink)

Check it Out

Here's another Volokh Conspiracy item: Eugene Volokh has an extensive criticism of a study purporting to show that carrying a gun does not afford protection against being shot. In fact, the study claims that people carrying guns are more likely to be shot than those unarmed. I haven't had an opportunity to read the study itself, so I can't confirm Volokh's criticisms, but they certainly sound plausible. The best that such a study can show is a correlation, rather than a causal relationship, between carrying a gun and being shot; or the lack of a correlation, rather than the lack of a causal relationship, between carrying and not being shot. It's plausible that people who carry guns do so because they are more likely to be shot at than those who don't carry, so it's possible that guns offer them protection even though they are shot at a higher rate than those who aren't packing.

Source: Eugene Volokh, "'Guns Did Not Protect Those Who Possessed Them from Being Shot in an Assault.'", The Volokh Conspiracy, 10/5/2009

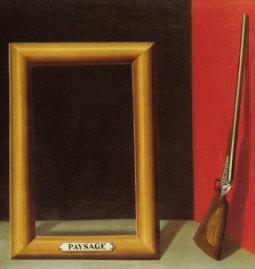

Acknowledgment: The illustration is a detail from René Magritte's painting Les Charmes du Paysage.

October 4th, 2009 (Permalink)

The Case of the Misplaced Comma

Law professor David Post of The Volokh Conspiracy has a post about the interpretation of sections 116 and 256 of the Patent Act, which are almost identical except for a single comma:

| 116 | 256 |

|---|---|

| Whenever through error a person is named in an issued patent as the inventor, or through error an inventor is not named in an issued patent, and such error arose without any deceptive intention on his part, the Commissioner [of patents] may permit the application to be amended… | Whenever through error a person is named in an issued patent as the inventor, or through error an inventor is not named in an issued patent and such error arose without any deceptive intention on his part, the Commissioner [of patents] may…issue[] a certificate correcting such error. |

According to Post, the courts have rightly interpreted these two sections as giving different conditions under which the Commissioner of patents may correct an error in the naming of an inventor in a patent. I agree with Post's interpretation of section 256, but I'm doubtful about 116, at least from a purely logical point of view.

Logically, the comma and other punctuation marks are scope markers, that is, they indicate the scope of logical parts of a sentence such as quantifiers and connectives. In sections 116 and 256, the difficulty concerns the scope of the connectives "and" and "or". In formal logical symbolism, scope is usually indicated with parentheses. In English, a comma usually marks scope in a similar way to a parenthesis. Suppose that you visit a restaurant whose menu says that with an entree you get:

Soup, or salad and vegetable.

This is similar in logical form to the antecedent of 256―that is, up to the last comma. Here, the comma indicates that soup is one choice, and salad together with a vegetable is another. Contrast that with a different restaurant whose menu says:

Soup or salad, and vegetable.

Now, the choice is between soup and salad, and you get a vegetable with either. Using parentheses, these two sentences would be represented as follows:

- Soup or (salad and vegetable)

- (Soup or salad) and vegetable

Suppose that you go to a third restaurant with the following on its menu:

Soup, or salad, and vegetable.

What would you get with your entree? If you order soup, will you also get a vegetable? It's ambiguous because the punctuation fails to make it clear which connective has the greater scope. Is the sentence a disjunction with a conjunctive second disjunct, or is it a conjunction with a disjunctive first conjunct? It's impossible to tell, yet this is the same punctuation as the antecedent of 116.

Given the ambiguity of 116, the courts may have to make a choice. I'm not sure what the basis of this choice is, but it can't be purely logical. Perhaps there's no apparent reason to treat the two types of error differently in terms of deceptive intent; if so, this would mean that the punctuation of 256 is in error. Another possibility is that the courts think that the rules must be interpreted differently because they are punctuated differently: otherwise, the extra comma would serve no purpose.

In any case, Post's main point is still correct: commas do matter because their placement can change the meaning of a sentence, and their misuse can lead to ambiguity.

Technical Appendix:

Sections 116 and 256 each express a rule concerning the conditions under which errors in patents can be corrected. As such, I will represent them as universally quantifying over errors. Following Post's terminology, let "Mx" mean that x is an error of misjoinder, "Nx" that it is an error of nonjoinder, "Dx" that it is without deceptive intent, and "Ix" that the Commissioner may issue a certificate to correct it. There are negations in both the nonjoinder clause and the deception clause, but they don't affect the scope issue, so I'm suppressing them. Now, here's a representation of 256:

(x){[Mx v (Nx & Dx)] → Ix}

So, what the rule says is that the Commissioner may issue a certificate to correct either a misjoinder or a nondeceptive nonjoinder, which is how Post and the courts interpret it. So far, so good; but what happens if you remove the comma, as in 116? The comma no longer serves to indicate whether the disjunction or conjunction has greater scope, so that the resulting sentence is ambiguous between (256) above, and:

(x){[(Mx v Nx) & Dx] → Ix}

This is a different rule, which says that the Commissioner may issue the certificate to correct either a misjoinder or a nonjoinder, provided that they were nondeceptive in intent. According to Post, this is how the courts actually interpret the ambiguous 116.

Source: David Post, "The Lowly Comma, Revisited", The Volokh Conspiracy, 10/1/2009

Solution to a Third Puzzling Picture: Mr. Murphy. Given that Mrs. Murphy is married, "my daughter's father" is presumably her husband. Thus, what she said is equivalent to: "this man's son is my husband's son". So, Mr. and Mrs. Murphy have both a son and a daughter, and "this man" is Mr. Murphy. Of course, it's possible that her daughter's father might not be her current husband, but Mr. Murphy would be the prime suspect.