Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

April 28th, 2016 (Permalink)

Headline

'Doctor Strange' turns Tibetan man into European woman

That's one strange doctor.

April 26th, 2016 (Permalink)

Book Review: Suspicious Minds

Title: Suspicious Minds

Subtitle: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories

Author: Rob Brotherton

Date: 2015

Quote: "A conspiracy theory, according to…literal-minded definitions, is essentially just a theory about a conspiracy. But when people call something a conspiracy theory, they're usually not talking about just any old conspiracy. Conspiracies, after all, are a dime a dozen. From outlaws plotting bank heists to corporate executives planning to mislead their customers, and from drug smuggling and bribery to coups, kidnappings, assassinations, and terrorist attacks, plenty of things [that] happen in the world are the result of conspiracy between interested parties or secret plots by powerful conspirators. There's nothing especially noteworthy about theorizing the existence of conspiracies like these. Our definition ought to reflect how people actually use the term, and in regular conversation not every theory about a conspiracy qualifies as a conspiracy theory. The term is more than the sum of its parts." (P. 62)

Review: I've had some criticisms of the subtitle of psychologist Rob Brotherton's new book, as well as of an article that Brotherton wrote for the Los Angeles Times―see the Resources, below. My guess is that the subtitle was imposed by its publisher as there is little in the book that supports it, but I stand by my criticism of both it and the newspaper article. Nonetheless, despite my previous criticisms, I have good news about this book: it's excellent!

If you know someone who believes "weird things"―and I suspect that most of us these days do know at least one conspiracy theorist (CTist)―and you wonder what makes them tick, then this book may help you understand. Why is it that an otherwise sane, intelligent person believes [insert your favorite conspiracy theory (CT) here]? Of course, I'm assuming that you don't also believe that CT, for if you did you wouldn't be puzzled.

Even if you're a conspiracist yourself, you can always find a CT so far out there that you wonder how anyone could take it seriously. So, if you do believe some CT, a useful thought experiment is to put yourself in the shoes of someone who doesn't: that person is thinking about you in the same way you think about your crazy CTist friend. So, you believe that JFK was assassinated by the CIA, but those 9/11 CTists are kooks. Or, maybe you're a 9/11 "kook" yourself, but those who claim that the moon landings were faked are lunatics.

My point here is not the bogus one that we're all CTists, but that even if you are a CTist about some particular CT, you are very likely to find yourself in the same position as the rest of us. How is it that those other CTists can believe that crazy stuff? In contrast, if you believe every CT out there, then this book isn't for you. In fact, you might want to get some therapy―just a suggestion.

Conspiracy thinking is a type of fallacious thinking, and fallacious thinking is normal human thinking. It's normal for people to think poorly much of time and in many situations, especially when nothing of immediate serious consequence is at stake, and because it's normal none of us is immune. However, that doesn't mean that some of us do not think better than others, or that we can't all learn to think better. Learning about conspiracy thinking―what it is, how to recognize it, and how to resist being seduced by it―is one way to improve your thinking.

This book is not a history of CTs―though we do learn a little in the first chapter―nor is it a book aimed at debunking specific CTs―though a bit of debunking is done in passing. In the first chapter, we discover that CTs have always been with us, though perhaps not to the degree that they are today. If one is tempted to believe that CTs are just harmless entertainment, or all CTists delightful eccentrics, the second chapter explains that there can be great harm in conspiricist thinking. In particular, Nazism was a CT based on a plagiarized forgery. Of course, most CTs are not as destructive as Nazism, but that's about like saying that most diseases are not as bad as AIDS.

I've argued previously―see the Resource under "Confirmation Bias", below―that CTs are not genuine theories since they lack one necessary characteristic of theories, namely, falsifiability. This is one reason why arguing with CTists can be such a frustrating experience, as Brotherton explains:

…[A]ttempting to refute a conspiracy theory is like nailing jelly to a wall. …[T]he theory is always a work in progress, able to dodge refutation by inventing new twists and turns. Each debunking can be construed as disinformation designed to throw truth seekers off the scent, while the conspiracy theorists' continued failure to blow the lid off the conspiracy merely testifies to the power of their enemy (and the gullibility of the masses). Conspiracy theories aren't just immune to refutation―they thrive on it. If it doesn't look like a conspiracy, it was definitely a conspiracy. Evidence against the conspiracy theory becomes evidence of conspiracy. Heads I win, tails you lose. (P. 77)

Since Brotherton is a psychologist, the aim of the book is to explain what is known about the psychology of conspiracist thinking. Regular readers of The Fallacy Files should already be familiar with many of the psychological phenomena that play a role in CTs:

- Black-or-white Thinking: Chapter 7

Fallacy: Black-or-White

- Post Hoc Thinking: Ch. 8

Fallacy: Post Hoc

- Over-Sensitive Pattern Detection: Also ch. 8

One skill in which people are still far superior to computers is pattern detection. At mathematical operations, or even games such as chess or go, computers can now beat even the best people. But an average person can recognize human faces far better than the best computer can. In a sense, we are too good at this task in that we err on the side of detecting patterns even when they aren't there. For instance, we all have a tendency to see patterns in random arrangements such as clouds and inkblots. The connection to conspiracy theorizing should be obvious, namely, that most CTs are like the faces or animals that one sees in clouds: they're patterns that aren't really there.

- Over-Sensitive Intention Seeking: Ch. 9

This is the tendency to anthropomorphize everything, interpreting every event in terms of human motivations. Like pattern detection, this is a useful and important human skill, but people tend to overdo it. For example, CTs have grown up around accidents, such as the death of Princess Diana, because people are unhappy when an important person dies from unintended causes.

- "Proportionality Bias": Ch. 10

A causal heuristic that people use is that effects have proportionate causes, so that events that we take to be big and important must have big, important causes. Here's what Brotherton has to say about it:

…[T]his isn't always a bad rule of thumb. A lot of the time, big events really do have big causes. If you pick up a rock and give it a gentle toss, you won't be surprised to find that it doesn't get very far. But reel back, wind up, put everything you've got into it and it'll go much farther. … We know the bigger effort will produce a bigger effect. … But it's not always true that the size of the cause matches the size of its consequence. Sometimes one small twist of circumstance can change the course of our lives.

The proportionality bias plays a role in many CTs, such as the granddaddy of all CTs, the assassination of President Kennedy: many people are reluctant to accept that a lone loser such as Lee Harvey Oswald could have murdered the most powerful man in the world. A traditional poem makes this point:

For the want of a nail a shoe was lost,

For the want of a shoe a horse was lost,

For the want of a horse a rider was lost,

For the want of a rider a message was lost,

For the want of a message a battle was lost,

For the want of a battle a kingdom was lost,

All for the want of a horseshoe-nail. - Confirmation Bias: Ch. 11

Resource: Check it Out, 11/21/2013

I could nitpick Suspicious Minds on a few minor points, but I don't want to; instead, I want to encourage you to read it. I do think the author tends to err on the side of tolerance of CTs, despite discussing the wacky theories of David Icke, who appears to have adopted his beliefs from the old science fiction television miniseries V. If Icke's theories aren't "crazy", then I'm a shape-shifting reptile from another dimension. However, no book is perfect. So, I highly recommend Suspicious Minds to anyone puzzled by the phenomenon of conspiracy theories, and nowadays that should be just about everyone.

Resources:

- A New Book for a New Year, 1/6/2016

- The Illogic Behind Conspiracy Theories, 1/25/2016

April 17th, 2016 (Permalink)

Million Two-Thousand Student March

A couple of days ago the "Million" Student March was held on over a hundred campuses nationwide. Apparently, this is not the first such march to take place, as a previous march was held on November 12th of last year. According to the organizers' website, the previous march took place on 115 campuses and "over 10,000 people" marched. Well, a million is certainly over 10,000. However, assuming that the organizers aren't intentionally understating the number of marchers, they appear to have missed their target by two orders of magnitude.

More likely, 10,000 is an overstatement, since the organizers of political marches are not given to modest understatement. Rather, they wish to suggest that their movement has many supporters and, thus, a lot of democratic political clout. It's this same motivation that leads them to call their demonstration the "million X march" in the first place. However, ever since the first such march―see the Resource, below―the one thing you can say for sure about a "million X march" is that a million Xs did not march.

Exactly how many students did march? It's hard to find any other source of information other than the organizers' own dubious claim about last year's march, so let's try to estimate this year's based on news reports. According to The Daily Caller, fifteen people marched at the University of Missouri, twenty at UCLA, and about 25 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Generously assuming that the average turn-out on each of 115 campuses was 25, that means the total attendance this time around will be less than 3,000. Not only that, but the Daily Bruin report of the UCLA march makes it clear that the twenty marchers included "alumni and workers" in addition to students. Again, let's be generous and assume that at least two-thirds of the marchers are students; then the organizers might be justified in calling it the "2,000 Student March".

Sources:

- Million Student March, Accessed: 4/16/2016

- April Hoang, "Million Student March protestors demand university reforms", Daily Bruin, 4/13/2016

- Eric Owens, "‘Million Student March’ Attracts Dozens Of Protesters Around America, Is A Hilarious Failure", The Daily Caller, 4/14/2016

Resource: The Million "Million X March" March, 6/18/2014

April 8th, 2016 (Permalink)

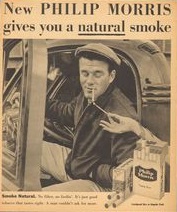

Call for Philip Morris

In researching the contextomy of Margaret Sanger discussed in the previous post, I discovered that the quote came from a television interview that Sanger had done with the late Mike Wallace. Specifically, the interview came from a half-hour show called The Mike Wallace Interview. Wallace is, of course, best known for the later show 60 Minutes, which is still on the air.

This post has nothing to do with the Sanger quote, but with the advertising included during the interview, specifically ads for Philip Morris cigarettes. The show aired in 1957, which is long before cigarette advertising ceased on television in 1971. It's also from a time period when TV shows often had a single sponsor, and that sponsor for Wallace's show was Philip Morris. So, there's nothing surprising about the fact that there are cigarette ads during the interview.

What did surprise me, however, is that Wallace himself endorses Philip Morris cigarettes during the ads. Now, it was common at the time for the hosts or stars of TV shows to do the ads themselves, so perhaps I shouldn't be so surprised. However, Wallace is now remembered as a television journalist, and a reporter doing advertisements―let alone endorsing products―would surely be at least frowned upon. As a result, I found the beginning of the program a bit startling:

Mike Wallace: … My name is Mike Wallace, [holds up cigarette] the cigarette is Philip Morris.Announcer: New Philip Morris, probably the best natural smoke you ever tasted, presents The Mike Wallace Interview. …

Wallace: My guest's opinions are not necessarily mine, the station's or my sponsor's, Philip Morris Incorporated, but whether you agree or disagree, we feel that none should deny the right of these views to be broadcast. One might say that the basis of this program is fact and fiction. And using that yardstick I'd like to apply it to something I usually talk about at this time and that is this: Philip Morris cigarettes. Here's why I smoke 'em and enjoy them. Fact One: Today's Philip Morris is no ordinary blend, it's a special blend, of domestic and imported tobaccos. Opinion? My taste may be different from yours, but on this I think we can agree. This cigarette tastes natural; I think you'll like it. …[S]o get with Philip Morris yourself and check these facts. When you do, I think you'll find it's probably the best natural smoke you ever tasted. And now to our story. …

Source: "Guest: Margaret Sanger", The Mike Wallace Interview, 9/21/1957

We see here two common fallacies of advertising at work:

- Mike Wallace was a celebrity, the star of the show, and a reporter. A naive viewer, such as a young person, might not realize that Wallace was paid to endorse Philip Morris. Moreover, the way in which the ads are integrated into the program, with Wallace turning to the camera to sell cigarettes, could give the impression that his endorsement was a consumer report rather than a commercial.

Fallacies:

- Wallace praises Philip Morris as a "natural smoke" and asserts that it "tastes natural". This was part of an ad campaign from the same year that the program aired―see the periodical ad shown for one of many examples from the period. Apparently, what was supposed to be "natural" about Philip Morris was that it was an unfiltered cigarette at a time when filtered cigarettes were growing in popularity. So, Philip Morris had American Spirit cigarettes beat by decades.

Fallacy: Appeal to Nature

Resource: Cancer: It's 100% natural!, 5/10/2010

As surprising as the beginning of the program is, its ending is jaw-dropping:

Margaret Sanger: …Mr. Wallace, I've never smoked, but I'm going to begin and take up smoking and use Philip Morris as the cigarette for me to take.Wallace: Well, I thank you very much Mrs. Sanger. … These few seconds at the end of the interview are among the most enjoyable of the week for me. For much as I enjoy smoking during the interview with Mrs. Sanger, I believe I enjoy this cigarette most right now. Of course, Philip Morris is easy to enjoy and the taste is natural…. Which is why I say get with Philip Morris, probably the best natural smoke you ever tasted.

Mike Wallace was surely being paid for his endorsement, either directly or through the sponsorship of his program, but was Sanger also paid? Given Sanger's controversial status, it's hard to believe that Philip Morris would even want her endorsement. However, if she wasn't being paid, why in the world did she say what she did? She laughs after saying it, so maybe it was her idea of a joke.

April 4th, 2016 (Permalink)

What's New?

I've added another contextomy to the Familiar Contextomies page, this one another case of Margaret Sanger being quoted out of context―see the Source, below. As I mentioned when introducing the first one, Sanger is a rich source of contextomies, as well as fake quotes, misquotes, false attributions, and misinterpretations―see the Resource, below. Check it out.

Source: Margaret Sanger, Familiar Contextomies

Resource: What's new?, 7/20/2015

April 1st, 2016 (Permalink)

Riddle

What is the capital of America?

A

Source: Richard Lederer, The Bride of Anguished English (2000). The riddle was suggested by one from page 17.